Editor’s Note: Peniel E. Joseph is the Barbara Jordan chair in ethics and political values and the founding director of the Center for the Study of Race and Democracy at the LBJ School of Public Affairs at the University of Texas at Austin, where he is also a professor of history. He is the author of several books, most recently, “The Sword and the Shield: The Revolutionary Lives of Malcolm X and Martin Luther King Jr.” The views expressed here are his own. View more opinion articles on CNN.

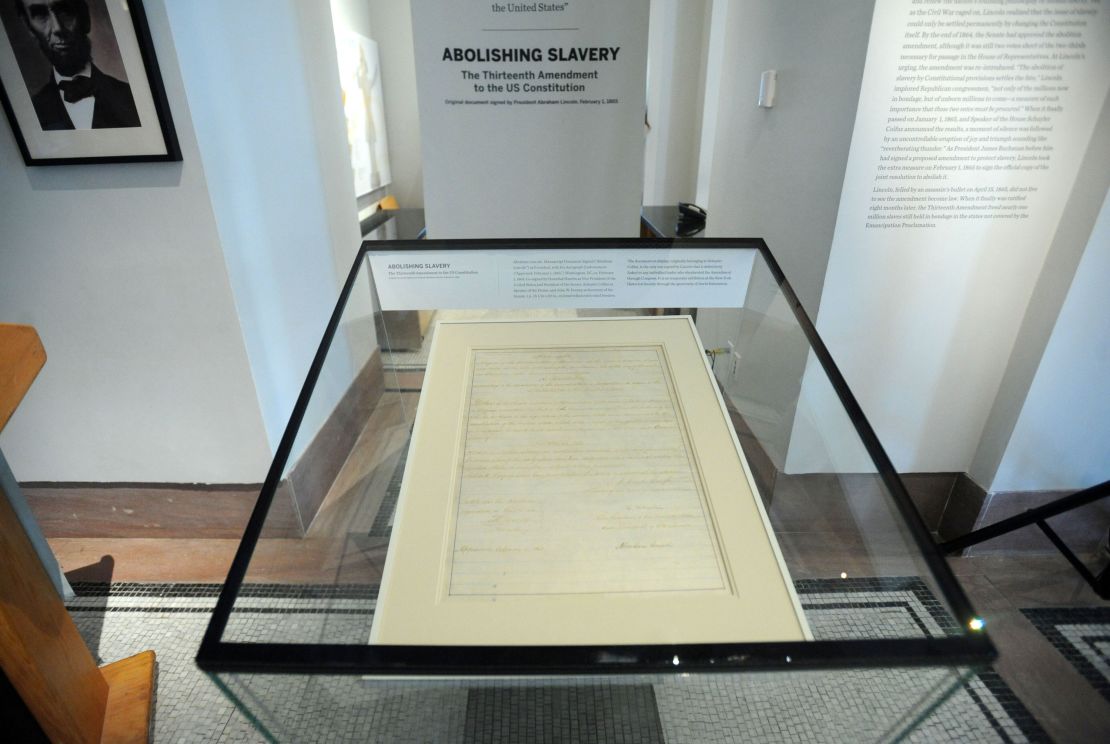

This week marks the 155th anniversary of the ratification of the 13th Amendment to the US Constitution that banned racial slavery. At the time this marked a new birth of American freedom, one that came at a such a high cost – and remains so incomplete – that many Americans tend to gloss over the contemporary challenges left in its wake.

The end of 2020 also finds America at another crossroads in our tragic racial history. Three significant events have cast a particular spotlight on the gaps between the promise of American democracy and our unequal reality. The disparate impact of the Covid-19 pandemic continues to ravage Black and brown communities in the US. The resurgence of the Black Lives Matter movement – sparked by the killings of George Floyd and Breonna Taylor – continues to galvanize both global protest and drive a searing national conversation about systemic racism. Both of these factors helped to alter the political climate by paving the way for Joe Biden to be elected president after perhaps the most racially divisive presidential campaign season in history.

The 13th’s abolishment of racial slavery or “involuntary servitude” came with one extraordinary caveat, the amendment’s glaring flaw; it made an exception in the case of those citizens found guilty of a criminal offense. This defect helped institutionalize the system of mass incarceration that 21st century freedom dreamers are now working so hard to dismantle.

The amendment’s allowance of forced bondage as a form of punishment for criminals is perhaps the most extraordinary bait and switch in American history. It helped to negate the worry about labor competition between newly emancipated Blacks and the White working class. Southern oligarchs, once fearful that the end of the Civil War might bring about land redistribution and criminal trials, found themselves resuming in large part the roles they had before the conflict.

Immediately after slavery’s formal end, convict leasing began – a system targeting unemployed freed men and women by charging them with crimes. The system of cash bail, fines, fees and criminal warrants innovated during the early years of Reconstruction helped to exploit a new labor force “leased” out to companies who paid local municipalities a fee per “convict.” Ava Duvernay’s searing documentary “The 13th” has introduced this history and its relationship to mass incarceration and the continued exploitation of Black people to a new generation and a much wider audience.

The parallels between our own time and 1865 are especially striking; both moments are defined by national political debates shaped by the struggle for Black citizenship and dignity. In many ways America is in the midst of a Third Reconstruction that echoes elements of its First.

Racial slavery’s demise threatened long-standing political and economic institutions that upheld White privilege and power in America. President Andrew Johnson’s approach to Reconstruction held the line by envisioning a nation where little had changed except the legal status of Black people on paper. White control over Black bodies could continue by ensuring that the Confederacy went unpunished, the redistribution of land to freed slaves halted and states’ rights remained sacrosanct enough to defy the spirit of any constitutional amendment (and a few in particular) with impunity.

After the passage of the 13th Amendment, Southern states instituted “Black Codes” designed to disenfranchise Blacks and weaponize anti-Black violence as a purposeful strategy to maintain White political and economic domination over newly freed African Americans.

Today’s system of disenfranchising convicted felons has its roots in Reconstruction-era racist policies designed to capitalize on the flaws in the 13th Amendment to stop Black people from voting. Even after Floridians voted in 2018 to restore voting rights to former felons, the legislature instituted a de facto poll tax to prevent Black residents who had served prison time from being enfranchised. Widespread voter suppression efforts largely targeting Black Americans have been a defining feature of the modern-day political landscape, especially following the 2013 Supreme Court decision gutting portions of the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

Americans committed to racial justice must remember the past as we seek to carve out a more hopeful political future that, partially because of the 13th Amendment’s shortcomings, continues to prove elusive in our own time. The focus of that fight cannot be a single issue or community; it must be America’s system of policing and punishment, which has served for so long to wreak mass havoc on the bodies, minds and families of Black Americans.

Movements for the abolition of slavery in the 19th century, as those to defund or abolish the police do now, rested on efforts to overturn an evil system that dehumanized Black people under the cover of legal and political arguments, against all contrary evidence, that the system offered the best protection and benefits for everyone. “You lost a big audience the minute you say it,” President Barack Obama recently argued of “defund the police,” “which make it a lot less likely that you’re actually going to get the changes you want done.” While Obama’s words have resonated deeply especially among center-left and right leaning Americans, his comments make for poor history.

When it comes to questions of Black citizenship and dignity, branding is never the problem. Even after the abolition of slavery, public hearings and Freedmen’s Bureau investigations revealed “violence against ex-slaves, including whippings, ritualistic torture, and murders.” For the generation of Black Americans who struggled for equality in the wake of the 13th Amendment, opposition came not from how their demands for justice were phrased but that they were demanded at all.

This generation of Americans, unlike those living in slavery’s immediate aftermath, have the profound opportunity of writing a new chapter in our nation’s history. Words unmatched by deeds will not be enough.

The 13th Amendment failed to fundamentally transform the structures of anti-Black violence and degradation that contoured Black lives. Instead, it offered a formal equality before the law, one that could technically be ripped away from those accused of being criminals. The badge of the criminal then, replaced the mark of slavery, creating a new caste system that persists into the present. The 13th Amendment’s 155th anniversary should be one of not just celebration but mourning as well – for the opportunities for systemic change America has already squandered. Those possibilities need, now more than ever, to be recovered.