Editor’s Note: Jane Greenway Carr (@janegreenway) is social and cultural commentary editor for CNN Opinion. She is a writer, scholar and former ACLS/Mellon public fellow at New America. She is the co-founder of The Brooklyn Quarterly. The views expressed here are solely hers.

As a schoolchild growing up in Tennessee, I visited the battlefields of Fort Pillow and Shiloh and toured Andrew Jackson’s home, the Hermitage. When I was a teenager, I haunted the blues clubs of Beale Street (the ones that would let me in without ID). I have watched football at the Liberty Bowl and basketball and bands at the Pyramid (before it became a Bass Pro Shop), I have driven through the Smoky Mountains and walked the floor of the Tennessee State House. (I have not been to Dollywood. I know, I hate myself too.)

But until I read Connor Towne O’Neill’s “Down Along With That Devil’s Bones: A Reckoning With Monuments, Memory, and the Legacy of White Supremacy,” I did not know this about my home state: It is also home to 31 monuments to Confederate general and native son Nathan Bedford Forrest – more than the state’s three presidents (Jackson, Andrew Johnson and James K. Polk) combined.

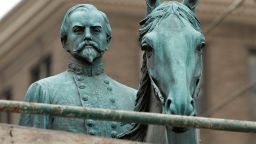

Towne O’Neill shares this fact early in his recent debut, an exploration of the regional footprint left by Forrest – known by fellow Confederates as “Wizard of the Saddle,” by the other side as the “Butcher of Fort Pillow” (Forrest’s men brutally massacred more than 100 surrendering Black Union soldiers) and by history as the first Grand Wizard of the Ku Klux Klan.

Forrest was the most promoted soldier on either side of the Civil War by 1865, rising from private to lieutenant general with military prowess that Southern historian Shelby Foote deemed made him a “genius” and brutal atrocities that prompted Union General William Tecumseh Sherman to call him “That Devil.”

Towne O’Neill paraphrases architect Aldo Rossi to posit that “a city’s monuments also serve as containers for the collective memory of that place.” And while he does not put it quite this way, what he has done with this book about monuments and memory of Forrest – and what the public figures and activists on both sides he profiles in Alabama and especially in Tennessee have done – is pour out those containers in the public square, asking readers and neighbors alike to bear witness as every last drop spills loose.

The author describes his project as a “series of dispatches from the battlefields of our country’s symbolic landscape.” He takes the reader to Selma, where a Forrest statue went up after the city’s first Black mayor was elected. He goes from there to Murfreesboro, where Forrest Hall still stands on the campus of Middle Tennessee State University; less than an hour’s drive away comes Nashville, where an artist (and former lawyer for James Earl Ray, who shot and killed Martin Luther King, Jr.) forged in plastic what Towne O’Neill calls “our nation’s ugliest Confederate statue” of Forrest. Towne O’Neill spends a great deal of time in Memphis, where Forrest loomed menacingly in a statue by Charles Henry Niehaus over a downtown where Ida B. Wells denounced lynching until a Millennial activist and some creative city powerbrokers said once and for all, after Charlottesville, no more; the book concludes back in Montgomery, Alabama, where legendary lawyer Bryan Stevenson spearheaded the creation of a national memorial to lynching victims.

These stories of what Towne O’Neill saw and learned in Tennessee, bookended by Alabama, are told with a transplant’s eye and an adopted native’s heart. A White man from Pennsylvania who moved South for graduate school, he chronicles how his search for traces of Forrest becomes a reckoning with his own complicity in a history of white supremacy he shares with Confederate partisans whose politics repulse him. At one chance meeting in a Confederate cemetery, when a White man comes up to shake his hand in solidarity, Towne O’Neill writes: “Whether I liked it or not, they were putting this Forrest monument up in my name, too … To tell his story, I would have to revise the story I told about myself.”

Forrest’s tenacity – in life and after death – powers the narrative here. Unlike more patrician and better known Confederate figures like Robert E. Lee, Forrest was, as Towne O’Neill puts it, a “hard-bitten striver” – born into poverty in 1821 in Bedford County, Tennessee, and rocked by the violent death of an uncle whose debt nearly crushed his nephew, he made prodigious wealth as a slave trader in Memphis, selling African Americans into the plantation horrors of the deep South. (After the war, he would become an early adopter of “convict leasing,” a forced penal system that targeted African American men, virtually re-enslaving them).

Forrest died of diabetes-related disease in 1877 and was buried in Elmwood Cemetery. In the early years of the 20th century, he was disinterred and reburied (along with his wife) in the park that bore his name until 2013 (further underscoring, for many, the point of its monument). After the removal and renaming, Forrest’s earthly remains – now the property of the Sons of Confederate Veterans (SCV) – are destined for elsewhere.

In death, Forrest the emblem came to embody the essence of Lost Cause mythology, deployed at will to assert White dominance: “In his symbolic afterlife, Forrest haunts the landscape,” Towne O’Neill writes.

From this perspective, Forrest’s military exploits for the Confederacy and success in the business of slavery were not a defense of the social order into which he was born; they were an attempt to retain and elevate his self-made status – a life of American exceptionalism whose veneer of Confederate treason seems to bother a number of contemporary Southerners not at all. They embrace it.

Towne O’Neill – also known for his work as a producer on the “White Lies” podcast, an NPR production that was a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize for audio reporting for its investigation of the 1965 murder of Rev. James Reeb in Selma – treats some of these people with curiosity and humanity in his book. They range from Murfreesboro “townies” who don’t want university students telling them how to treat Confederate history to the woman in Selma (who also plays a significant role in “White Lies”) who cheerfully puts what can only be called Confederate propaganda in the author’s hands. These White Southerners, across geography and circumstance, are largely the ones for whom Forrest is a heroic figure embodying the power of self-determination; they use Forrest to profess a bootstrap gospel that circumstances of birth don’t mandate destiny (even though research suggests the contrary).

In one particularly striking episode that reveals the depth of such belief in their hero, Towne O’Neill visits a meeting with a Memphis chapter of the SCV, where members seek recommendations from each other on how to “choose between their church and Forrest” – after some of their pastors have signed a letter in support of removing the city’s Confederate monuments, they know they can no longer worship there.

Towne O’Neill walks a tightrope in trying to bring Forrest back to life in order to put him to rest. The line wobbles from time to time, but the book’s richest achievement lies in the author’s ability to make a Klansman the prism whose refracted light illuminates the shadows of racism in a post-2016 America.

He writes that his book “begins and ends with an empty pedestal” – an image of division for some, of progress for others. What that empty space means, Towne O’Neill implies, and what comes next, he says more explicitly, is up to us.

The following interview has been lightly edited for clarity and flow.

CNN: Why did you want to write this book?

Connor Towne O’Neill: I realized that I didn’t really understand my country – or that I didn’t live in a country that I thought I lived in. I went down this rabbit hole of studying this somewhat obscure Confederate general, as a way of figuring out what this country was built on – the inequities that this country was built on and how those inequities are perpetuated. Those stories stand in stark contrast to the kinds of rose-tinted stories of American exceptionalism that we just breathe like the air in this country. It was my way of making sense of the last couple of years of upheaval in this country too.

CNN: You talk about Confederate monuments “as a prominent theater of political war.” Can you elaborate on what you mean?

Towne O’Neill: These symbols didn’t just, you know, show up there overnight. They’re there because specific people with specific economic and political power wanted them to be there. And they reflect the racial and political views that those people hold. So they’re not just these figures of history, they’re very much a part of the present.

How they got there is political and whether they’ll stay there is political. Because symbols matter. This summer has made that even more abundantly clear – President [Donald] Trump giving a July 4th address in front of Mount Rushmore, protesters toppling monuments across the country. These symbols matter and are tied to our politics and to these questions that our country is wrestling with right now about whether our society can [fully] transform itself into a multiracial democracy. That was the question of the Civil War. That was the question of Reconstruction. That was the question of the Civil Rights Movement. And that is the question right now. And in each of those moments, as we’re asking those questions, monuments are coming up and coming down.

CNN: There is one passage where you describe the events in Charlottesville in 2017: “Ironically, by violently defending the traitors who made up the Confederacy, Unite the Right expressed something essential about American whiteness – as if their acrylic glass shields were meant for us to catch our reflections in.” What is the significance of Americans being confronted, in their own history and in the present, with “something essential about American whiteness”?

Towne O’Neill: As James Baldwin says, if we don’t know who we are, we don’t have any capacity to change. And we sorely need to change. As Americans, we don’t know ourselves because we don’t think about whiteness and we don’t think about what it means. But if you look at how whiteness has been constructed and enforced in this country, over centuries, there is no whiteness without a supremacy attached to it. That is what whiteness was invented to do. It was invented and is perpetuated to hoard opportunity and resources and wealth at the expense of others. It is a system of extraction and exploitation.

And that is a hard pill to swallow. It’s hard because White people don’t want to see it. They don’t want to see that an identity so many White Americans took for granted and haven’t thought much of about, has a real moral bankruptcy to it.

CNN: I wanted to ask what it was like to get to know some of the contemporary characters you bring to life – like Rev. James Perkins, the former (and first African American) mayor of Selma, Joshua Crutchfield, a graduate student at Middle Tennessee State University, Tami Sawyer, an activist (and now local politician) in Memphis. What it was like for you to connect with and hear from them?

Towne O’Neill: It was really important. Those connections helped me figure out the way that I needed to approach this material and how I needed to be self-reflective about my own place in it. Rev. Perkins, Joshua, Tami, all in their own ways, took moral responsibility for their cities. It was never just a symbolic debate for them – it was about equality, it was about justice, and it was personal. There’s so much to admire in that. And to a greater or lesser degree, they were kind of skeptical of me.

It really took some doing to get, for instance, Rev. Perkins to talk to me. He wasn’t going to agree to talk to me about what it meant to him, that a statue of Nathan Bedford Forrest went up during his week in office, until I was able to talk to him about what it meant to me that that statue went up during his first term in office. Which is to say, he was skeptical of me and we had to talk through how I was approaching this material and how I understood myself in this context. Because I think as we were talking about earlier, I think, it’s a tendency among some White people to feel like questions about race in America don’t really involve them. But of course, they do. We are the antagonists here, whether or not we want to be, and maybe for some only passively. But it implicates us, it shapes everything about our lives. We’re not at all exempt from it.

CNN: Did working on the “White Lies” podcast inform your approach to the book?

Towne O’Neill: Spending time in Selma while recording “White Lies” deeply informed my sense of the book. One of the slogans that Selma has is “From the Civil War to Civil Rights and Beyond.” And I think reporting out “White Lies” showed us that the lies that we told ourselves [about race] are what keeps us from getting to a beyond. The Forrest book obviously grapples with the Civil War side of this, but in each of them, I was seeing the unresolved tensions about race in America and how they keep us getting to the beyond.

CNN: You describe toward the end of the book two moving scenes – the dedication ceremony of a marker in Memphis acknowledging the location of Forrest’s slave mart, held on the anniversary of Martin Luther King Jr’s assassination. It includes a reading of the known names and ages of the slaves sold there. The other is your visit to the National Memorial of Peace and Justice in Montgomery, which memorializes victims of lynching. Both moments stirred in me this question: When it comes to monuments, is removal enough? If not, what’s the next step – acknowledgment, or would you use a different word?

Towne O’Neill: I think removal is a start. Telling the truth is the next step. Then understanding why those symbols were there, why some of us needed them, why they were there and why they have stayed with us for so long. Connecting them to issues of power and wealth. That can orient us to what’s next.

I think in some ways these Confederate monuments are weathervanes – they point in a direction that political winds are blowing. They start to go up not in the immediate aftermath of the Civil War but only after the former Confederates had undermined Reconstruction and returned the South to white supremacists’ rule – it’s only then that those monuments go up and they’re signal of that shift. I think now as they’re coming down, they can also be weathervanes and they can point us to the larger inequities that we need to address.

CNN: At one point, you quote a Greil Marcus essay about Elvis Presley, where he’s talking about how difficult it is to pinpoint watershed moments in people’s lives. No spoilers, but I will say that you share in the book what you think the watershed moment was in Nathan Bedford Forrest’s life. To ask you a big, huge, unfair question: After writing this book about monuments, memory and the legacy of white supremacy, what would you say are America’s watershed moments on race? Are they static, or do they change?

Towne O’Neill: I think we’re in one right now, which is itself a change. Reconstruction is another watershed moment. That was a moment where there was a possibility that we could be otherwise, and there was real progress in that direction. But it was undone. And then, during the Civil Rights Movement a century later, there was another moment. We could acknowledge that the game was rigged, could dream that maybe we could really foster a multiracial democracy.

But then we turned away from it again, toward “law and order” presidencies, the war on drugs, being tough on crime, fueling mass incarceration. Twice now, we’ve betrayed these massive movements to get us to live up to our highest ideals. Maybe this time will be otherwise, it’s certainly an opportunity. But I think the thing to remember is that there has always been this opportunity. We can always be otherwise.

CNN: If you could say one thing or tell one story to another White person about what you learned in researching and writing this book – I’m thinking particularly of a White American, someone who is willing to listen [to your side] but who maybe grew up learning that the Civil War was fought over states’ rights and not slavery – what would that thing or that story be?

Towne O’Neill: I guess I would tell them the story of the moments just before the Civil War broke out. You could look at the situation at a national level and take stock of the physical and spiritual torture that was taking place in the South. And the great extraction of wealth and all the financial instruments that were created to extract that wealth that was enriching the entire country [including the North]. I would try to get them to understand that everyone is implicated in this. And I would tell them the story of the lies that were told to justify slavery, which is just antithetical to the society that we tell ourselves we are – the lies about Black inferiority that were told to justify slavery.

I would [ask them to] look at that watershed moment right before the war so they could understand all of the complexities of that situation – the physical horror of it, the financial extraction and the ideology that was being used. Because those three things, in one way or another, are still at work in this country, they’ve just taken on different forms.

This is what Bryan Stevenson is getting at when he says that “slavery didn’t end in 1865, it just evolved.”

CNN: Your book isn’t a biography of Forrest, but you spent all of this time investigating him and living with his memory. I’m curious to know whether you still feel him with you? Do you get up, go about your day, with him still there in your mind?

Towne O’Neill: Yeah, I do. Like you said, it’s not a straight biography. I wanted to tell this story about his memory – and I wanted to have him be present. But at the end of the day, it was more interesting for me to understand him in the context of his moment, and to see the structures of his life that he moved along: [his involvement in] the Second Middle Passage – the movement of enslaved people down from the Upper South into the plantations of the Deep South. What it meant for the South to secede and what he was saying about that secession. And then of course how Reconstruction was overthrown by the Klan and how those policies of white supremacy were reimposed after the fall of Reconstruction.

That’s part of why I was interested in him. But I was also interested in what he could illuminate about the larger context that he was living in. So in that way, I think of him as a good teacher – that following his story taught me so much about how we wound up in this moment that we’re in. And while I find so many of his actions to be repugnant, it’s through him that I came to a deeper and more honest understanding of my country – and myself.