Story highlights

A rare double find of medieval neurosurgery and coffin birth was unearthed in an Italian grave

The woman was 38 weeks pregnant when she died a week after neurosurgery

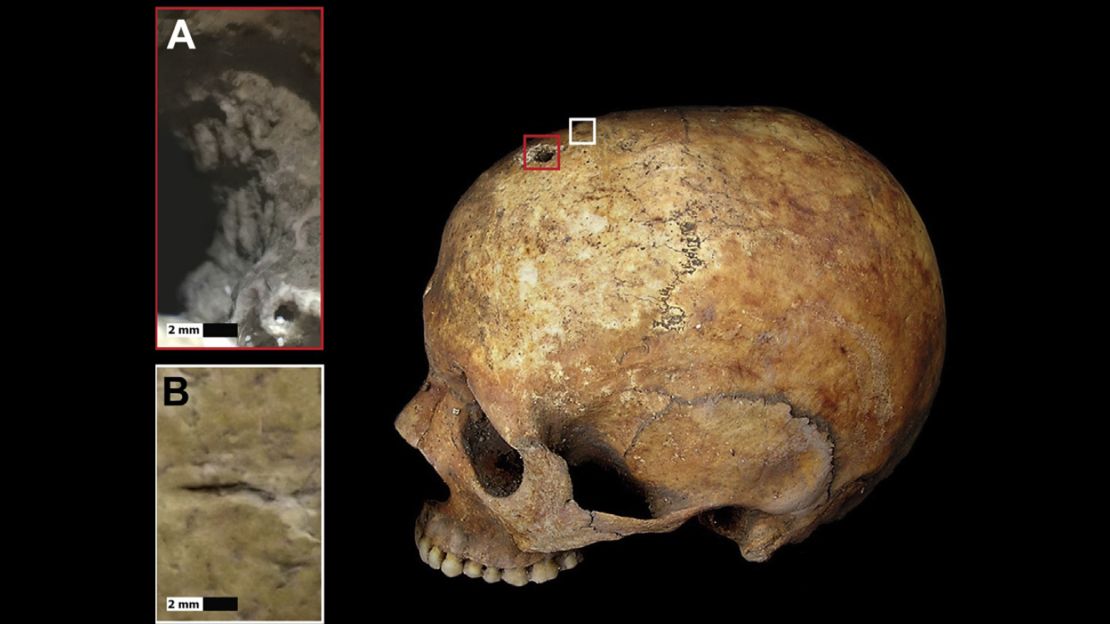

When the brick coffin of a young woman from medieval Italy was opened after its discovery in 2010, two peculiar things stood out to the researchers: There was a perfect hole in the frontal bone of her skull, and between her pelvis and legs, there was a series of smaller bones belonging to a baby.

This type of neurosurgery in which a hole is drilled or scraped into the bone, called trepanation, was performed a week before the woman’s death during the Lombard period, from the seventh to eighth century, in Lombard, Italy.

And although she was 38 weeks pregnant, she never had the chance to bring a baby into the world. Instead, it was a “coffin birth,” in which the fetus is posthumously extruded due to the force of gases and decomposition.

It is estimated the woman was between 25 and 35 years old.

This is the first time an example of trepanation and coffin birth have been found together.

Researchers from the University of Ferrara detailed this incredibly rare find in the journal World Neurosurgery.

Trepanation itself isn’t considered rare and was practiced as early as the Stone Age. But examples in the European early middle ages are less common. And examples of coffin birth are definitely rare.

“At the moment, this is the only known and published case of coffin birth from the Italian Early Middle Age,” Alba Pasini, study co-author and researcher with the Laboratory of Archaeo-Anthropology and Forensic Anthropology at the University of Ferrara, wrote in an email. “The trepanation is comparable to other interventions from the same period and from other cases of trepanation performed through drilling techniques.”

It is unknown why the woman had to undergo surgery, but the researchers said it’s possible it was connected to her pregnancy or an attempt to save her life so she could deliver the baby.

At the time, neurosurgery would have been used as an attempt to treat diseases, neurological or traumatic injuries or migraines. It was also used to treat hypertension in hopes of reducing blood pressure in the skull, so it’s possible this was a treatment for pre-eclampsia, a hypertensive pregnancy disorder, the researchers said. The symptoms, like fever, convulsions, cerebral hemorrhage or intercranial pressure, were all things treated by trepanantion at the time.

The researchers hypothesize that the woman had pre-eclampsia or eclampsia and that the surgery was to relieve the pressure she felt in her skull.

“This case study is really important, since it testifies that a medical approach to maternal morbidity actually existed during the Lombard period, despite the rejection of the scientific progress which denoted all the Early Middle Age,” Pasini said. “Also, it shows two rare findings, since post-mortem fetal extrusion is a quite rare phenomenon (especially in archaeological specimens), while only a few examples of trepanation are known for the European Early Middle Age.”

Cut marks on the skull point to obvious trepanation, and there are signs of bone healing around the hole. The researchers tested this area and determined the woman lived for one week after the procedure.

The intervention of neurosurgery wasn’t enough to save her, and she died with her fetus in her womb.

The researchers don’t know enough particulars of the case to guess whether the baby could have been saved even if its mother could not.

“The pregnancy lasted 38 weeks, so it was a late-stage pregnancy, almost reaching the birth moment; we can’t say if the baby could have been saved, since we do not know with certainty the specific disease which affected the woman or the specific treatments inferred by doctors,” Pasini said.

Otherwise, an analysis of her bones showed the woman was in good health, although it’s possible she had an illness before her death that wouldn’t be revealed by studying her skeleton.

Join the conversation

But it shines a light on what neurosurgery, and pregnancy, was like during this period. Pasini and her colleagues will continue to study more “peculiar cases from ancient times.”

“The oddity of this case is represented by the rarity of these findings; whether the two evidences are somehow linked or not, it’s been a truly lucky event to find them on the same individual,” Pasini said.