Story highlights

An unusual skeleton found in Chile has perplexed people for more than a decade

Whole genome sequencing revealed what caused its abnormalities

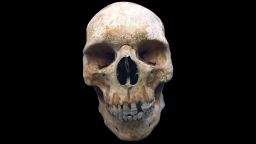

A mummified skeleton discovered in Chile’s Atacama Desert 15 years ago doesn’t look like anyone you’ve ever met. In fact, some would say it looks, well, alien.

It’s a skeletal conundrum made up of perplexing features. It’s only 6 inches tall – but initial estimates of the age of the bones were consistent with a child aged 6 to 8 years.

The long, angular skull, slanted eye sockets and fewer than normal ribs – 10 pairs rather than the normal 12 – only deepened the mystery.

Questions surrounding the discovery led to speculation that it was a previously unidentified primate or even an extraterrestrial life form.

The skeleton, dubbed Ata, was featured in TV shows and a documentary, “Sirius,” in which a UFO researcher attempts to figure out Ata’s origins.

Now, the authors of a study based on five years of genomic analysis want to set the record straight: Ata is human, albeit one with multiple bone disease-associated mutations. And they believe that their findings, published Thursday in the journal Genome Research, could help diagnose genetic mutation-based cases for living patients.

Investigating Ata

In 2003, Ata was found in a deserted mining town called La Noria, in Chile’s Atacama region. It was thought to be ancient at first, but initial analysis conducted in 2012 proved that the skeleton was only about 40 years old.This meant DNA would still be intact and could be retrieved for study.

The widespread speculation surrounding Ata brought the case to the attention of Gary Nolan, senior author of the new study and professor of microbiology and immunology at Stanford University.

“I learned about this through a friend who was interested in the entire area of extraterrestrial life,” Nolan wrote in an email. “He told me about a documentary coming out (‘Sirius’ … you can find it on Netflix now) which was to feature the ‘Atacama Humanoid.’

It was claimed that this was possibly the mummy of an alien.

“That was a significant claim in and of itself. More shocking though was the picture I was provided that was part of the online publicity. I decided to contact the movie directors (basically on a dare …) to tell them it was possible to do a sequencing of the specimen (if it had earthly DNA …) to determine its origin.”

Nolan and his colleagues signed a confidentiality agreement, and the directors agreed to report Nolan’s findings, even if the results indicated that Ata’s DNA was human.

Nolan wanted to study Ata for several reasons. The extraordinary specimen could have been a previously unrecognized primate species, some sort of human deformity or something else entirely. Nolan said he and his colleagues never believed it could be an alien.

They wanted an answer to the basic question: “What is it?”

DNA analysis would tell the true story. A sample extracted from the bone marrow of Ata’s ribs was used to conduct a whole-genome sequence analysis.

It was compared with human and primate genomes and determined to be a human female, probably a fetus, with Chilean ancestry. Although dating initially estimated the bone age of the skeleton at between 6 and 8 years, the researchers found that the remains had a rare bone-aging disorder that made them seem older than the person they belonged to.

At first, 8% of the DNA didn’t match with human DNA. Researchers determined that this was because of a degraded sample. An improved analysis matched up to 98%, Nolan said. Given the exposure and age of the skeleton, this wasn’t surprising. Then, they moved on to diagnosing the abnormalities.

It’s all in the genes

The researchers were looking for what might explain the skeleton’s small stature, as well as the abnormal rib count and other bone and skull oddities.

Dr. Atul Butte, another senior author of the study, was brought in to assist with evaluating the genome. Butte, the Priscilla Chan and Mark Zuckerberg distinguished professor and director of the Institute for Computational Health Sciences at the University of California, San Francisco, treated the analysis as though it were for a patient.

It revealed a number of mutations within seven genes. Together, these created bone and musculoskeletal deformities, like scoliosis, and skeletal dysplasia, known as dwarfism.

“There are mutations in many genes, including genes involved with the production of collagen (in our bones and hair), joints, ribs, and arteries,” Butte wrote in an email. “We know these genes are involved with these processes in human development, but we are still learning what all the other genes in the DNA do.”

Although the mutations found within the genes are known to cause bone disease, some of them had not been previously connected to growth or developmental disorders. The combination of genetic mutations explains Ata’s appearance, but it’s the number of mutations all present in the same specimen that surprised the scientists.

“It’s rare,” Butte said. “To our knowledge, no one has ever explained all of these symptoms in a patient before, and the changes in the DNA, or mutations, reflects this.”

But what could have caused this number of mutations?

Join the conversation

“Many times, genetic diseases are passed on from parents that are carriers,” Butte said. “In this case, these mutations are so rare that we haven’t actually ever seen some of these before, so it’s hard to imagine there are carriers out there. We do speculate that the environment where this child was developing might have played a role. The specimen was found in a town with abandoned nitrate mines, and exposure to nitrates might have caused the mutations. But it’s only speculation.”

No other researchers have seen the remains.

The way Nolan, Butte and their colleagues used their analytical tools to understand the mysteries presented by Ata’s skeleton may provide a pathway for analysis of multiple genes to discover the roots of mutations.

Butte said he hopes that the technology and tools used in this study can help patients and their families receive diagnoses quicker, as well as helping to develop treatments for conditions that can be traced to genetic mutations.

“Many children’s hospitals now see patients or children with unusual syndromes, including those never described before,” Butte said.

“DNA sequencing is now more commonly used to help us solve these ‘undiagnosed diseases.’ But many times, we tend to search for a single gene mutation that might explain what we see in the patient.

“What this case taught me we that sometimes there might actually be more than one major DNA difference involved in explaining a particularly hard-to-explain patient. We shouldn’t stop a search when we’ve found the first relevant mutation; indeed there might be many others also involved.”