Story highlights

Opioid overdose ER visits soared 30% from July 2016 to September 2017, CDC study finds

"This is a wake-up call for all of us," acting CDC director says

A study also found that treating pain with opioids was not superior to treatment with non-opioid medications

The opioid epidemic in the United States shows no signs of slowing, according to a Vital Signs report released Tuesday by the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The report found that emergency department visits due to suspected opioid overdoses continued to climb – about 30% – from July 2016 to September 2017 across the country.

“This is really a fast-moving epidemic that’s getting worse,” said Dr. Anne Schuchat, acting director of the CDC and acting administrator of the Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry, who was not an author of the report.

“The increases in overdoses were seen in adults of all age groups. They were seen in men and women. They were seen in every geographic region in the nation,” she said.

The findings in the report could help identify and track overdoses in a way that helps the development of responses from both the medical community and law enforcement agencies, Schuchat said.

Based on the report, some emergency departments could enhance prevention and treatment and improve efforts to connect patients with resources to help prevent future overdoses.

“We really think that this is a wake-up call for all of us – that the opioid epidemic is in all of our communities and that there’s more that we need to do,” Schuchat said.

Potential for misuse

US Surgeon General Dr. Jerome Adams said Tuesday that the country’s opioid epidemic hits particularly close to home.

“My younger brother has struggled with addiction for decades, and I often think about the fact that it could have been me,” he said. “My whole family, like many other families in America, have experienced a similar story and over the years have witnessed firsthand the pain that comes from opioid use disorder, which is commonly referred to as addiction.”

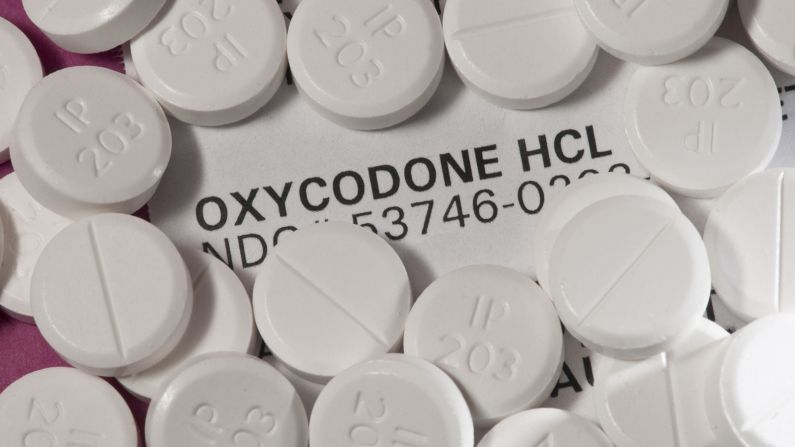

Opioids are a class of drugs used to reduce pain, and they have the potential to be misused. Prescription opioids can be prescribed by doctors and include oxycodone or OxyContin, hydrocodone or Vicodin, and morphine.

Pharmaceutical fentanyl is an opiate drug that is about 50 to 100 times more potent than morphine, and it is usually administered to patients who are in severe pain through injection, a patch or a lozenge.

Most of the fentanyl that people buy on the street, however, doesn’t come from pharmacies or hospitals. Rather, much of it is illegally made in clandestine labs as chemical variations of legal fentanyl.

Heroin is an illegal opioid that is highly addictive. Between 2010 and 2016, the rate of heroin-related overdose deaths increased by more than five times, according to the CDC.

Every day, more than 115 people in the US die after overdosing on any type of opioid, according to the National Institute on Drug Abuse.

The states with the biggest rise in overdoses

The new report included data on emergency department visits from July 2016 to September 2017 from the CDC’s National Syndromic Surveillance and Enhanced State Opioid Overdose Surveillance programs.

The data showed that among about 91 million emergency department visits identified in the National Syndromic Surveillance Program, which includes 45 states, a total of 142,557 were suspected opioid overdoses.

Those visits increased 29.7% from July 2016 to September 2017, but the CDC researchers found that there were some regional differences, too.

The Midwest had the largest increase of prevalence, at 69.7%; followed by the West, at 40.3%; Northeast, at 21.3%; Southwest, at 20.2%; and Southeast at 14%, the data showed.

Among about 45 million emergency department visits identified in the Enhanced State Opioid Overdose Surveillance Program, which includes 16 states, a total of 119,198 were suspected opioid overdoses.

Those visits increased 34.5% from July 2016 to September 2017, the researchers found, and 10 states experienced significant increases in prevalence during that time period.

Wisconsin had the largest increase, 108.6%, and Delaware had the second largest, 105%. Pennsylvania saw a 80.6% increase, Illinois saw a 65.5% increase, Indiana saw a 35.1% increase, Maine saw a 34% increase, North Carolina saw a 31.1% increase, Ohio saw a 27.7% increase, and Missouri saw a 21.4% increase. In the West, Nevada saw a 17.9% increase, and New Mexico saw a 8.3% increase.

Meanwhile, a significant decrease occurred in Kentucky: 15%. New Hampshire saw a 7.1% decrease, and a non-significant 5.3% decrease was observed in West Virginia. It is unclear whether those decreases are true declines or merely statistical fluctuations, Schuchat said.

The researchers noted that the increases in the Midwest were consistent with trends in previously reported opioid overdose deaths. Yet the increases in the Southwest and West and the decreases in the Southeast were unanticipated. Those findings might foreshadow death trends to come, they noted.

“Research shows that people who have had an overdose are more likely to have another. Emergency department education and post-overdose protocols, including providing naloxone and linking people to treatment, are critical needs,” Alana Vivolo-Kantor, first author of the report and a behavioral scientist in the CDC’s National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, said in a statement Tuesday.

The drug naloxone can reverse opioid overdose. Based on research presented at the American College of Emergency Physicians’ annual conference last year, naloxone was found to be successful in stopping overdose 93% of the time.

“Data on opioid overdoses treated in emergency departments can inform timely, strategic, and coordinated response efforts in the community as well,” Vivolo-Kantor said.

The new CDC report had some limitations, including that the data sources could have underestimated or overestimated opioid overdoses based on differences in how hospitals coded their emergency department visits.

Also, the findings were representative of only the hospitals participating in the CDC’s surveillance programs and were not generalizable to areas not participating in those programs.

Overall, the new findings underscore just how serious the opioid epidemic has become, said Dr. Caleb Alexander, an associate professor and co-director of the Center for Drug Safety and Effectiveness at Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health.

He added that the trends described in the report are consistent with reports of worsening injuries and deaths.

“In 2016, more people died from drug overdoses than ever before in the United States. More than 60,000 people died in 2016, and this represented about a 20% increase from 2015,” said Alexander, who was not involved in the new report.

In December, the CDC’s National Center for Health Statistics released a data brief detailing those trends in the lives lost to drug overdoses in 2016.

“What this new report does is, this shines a brighter light on one particular facet of the epidemic, namely emergency department visits arising from overdoses,” Alexander said.

“Just as more people are dying from prescription opioids, heroin and illicit fentanyl, this report highlights that more people are also being seen in emergency departments for overdoses from these products,” he said.

Opioids might not be best for pain

The World Health Organization has described the epidemic of opioid overdoses and deaths in North America as being fueled by increased prescribing and sales.

About 40% of opioid overdose deaths involve a prescription opioid, according to the CDC.

Yet a separate study published in the journal JAMA on Tuesday found that treating pain with opioids was not superior to treatment with non-opioid medications over a 12-month period.

The study involved 240 patients diagnosed with chronic back, hip or knee pain recruited from 62 Minneapolis VA primary care clinicians from June 2013 to December 2015.

For the study, the patients were separated into two randomized groups: One group was treated with opioids, and the other received non-opioid medications.

Each group had a three-step prescribing strategy. For the non-opioid group, patients were prescribed acetaminophen and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs in the first step. Step two included additional oral medications, such as nortriptyline or amitriptyline and topical analgesics. Step three included drugs like pregabalin or tramadol.

For the opioid group, the first step was immediate-release morphine, oxycodone or hydrocodone. Step two included morphine sustained-action and oxycodone sustained-action, and step three was transdermal fentanyl.

The researchers found that there was no significant difference in pain-related function and health-related quality of life between the two groups over 12 months.

Rather, the researchers found that non-opioid medications were associated with significantly better or lower pain intensity, but opioids caused significantly more medication-related adverse symptoms. No deaths or opioid use disorder diagnoses occurred during the study.

The researchers wrote that their “results do not support initiation of opioid therapy for moderate to severe chronic back pain or hip or knee osteoarthritis pain.”

On the other hand, many patients with chronic pain need some type of relief and turn to opioids for care.

Join the conversation

Since 1999, the prescribing of opioids has increased substantially, and that has led to a large number of Americans developing opioid use disorder or addiction, the CDC’s Schuchat said. She added that the opioid epidemic has come in three waves, and overprescribing represents just the first.

“The second wave occurred related to heroin – where the heroin supply was inexpensive and extremely potent, and so in the population that was addicted to opioid medicines, the exposure to heroin was quite deadly,” Schuchat said.

“This third wave that we’re experiencing right now is related to fentanyl and other illicitly manufactured opioids that might be either injected or taken as pills, and this latest illicit product is even more potent than the heroin,” she said. “So even without an increase in people who are using opioids, the use of an opioid is even more dangerous than it used to be.”