Story highlights

Pain management can include behavioral, occupational and physical therapies

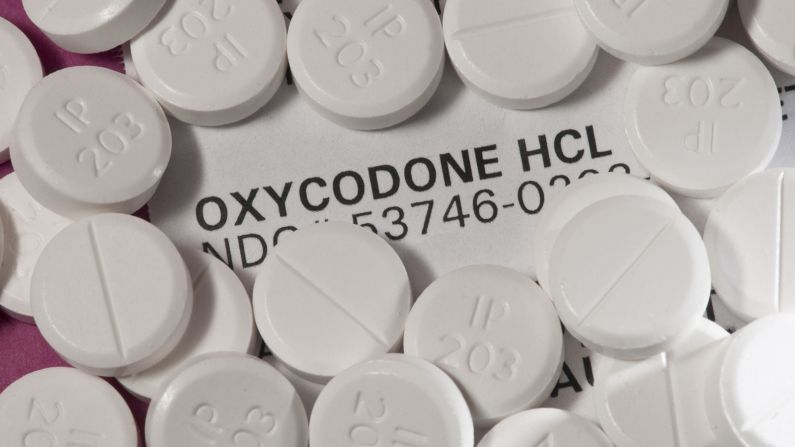

About 10 million Americans are prescribed narcotics for chronic pain

Last year, when the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention established new guidelines on prescribing opioids, it recommended that long-term opioid users be weaned or tapered off pain pills. A study published this week in the journal Annals of Internal Medicine bolsters this idea, finding that chronic pain patients who taper off opioids can have a better quality of life without them.

According to the American Academy of Pain Medicine, 100 million Americans suffer from chronic pain. And for many of those with chronic pain, treatment has consisted of narcotic painkillers. But long-term use also carries an increased risk of dependency and overdose, and an opioid overdose epidemic is ravaging the United States: It claimed more than 33,000 lives in 2015, half of them associated with prescription drugs.

For the approximately 10 million Americans who are prescribed long-term opioid therapy to manage their pain, what alternatives are there?

“It’s counterintuitive that pain and well-being could be improved when you decrease pain medication. …Patients felt better when dosages were reduced,” said Dr. Erin Krebs, medical director of the Women Veterans Comprehensive Health Center, part of the Minneapolis Veterans Affairs Health Care System, and an author of the study.

Krebs and her colleagues evaluated 67 studies that considered more than 12,000 patients and evaluated the effectiveness of various ways to reduce narcotic pain management, including buprenorphine-assisted programs, behavioral therapy programs, ketamine-assisted dose reduction programs, acupuncture and interdisciplinary pain management programs that incorporate physical or occupational therapies along with behavioral therapies such as counseling and exercise.

Many of the studies accounted for a decrease in pain among patients as well as increased mobility and overall increase in quality of life. However, the analysis, which was funded by the Veterans Health Administration in the Department of Veterans Affairs, had some significant limitations: Many of the studies evaluated were not double-blind controlled studies, considered to be the gold standard in science. However, of the studies they considered, at least 16 were of good or fair design. In addition, the studies evaluated whether patients stopped using opioids because the narcotic therapy had actually eliminated pain.

“This study provides needed information for providers about how to taper and/or discontinue opioids safely and effectively – that is, with nonopioid treatments, slow reductions in opioid dosage, patient buy-in, and close monitoring,” the CDC’s Tamara Haegerich, who wrote an editorial accompanying the study, wrote in an email.

Lots of gain, little pain

The most successful programs had an interdisciplinary approach. “All these studies involved new therapies and close followup and a team – maybe a physician working with a nurse and therapist – to help with the process,” Krebs said.

Suddenly withdrawing from opioids is difficult because withdrawal symptoms can be severe. “It’s not just they are experiencing excruciating pain. Panic sets in; it’s a psychological response. It’s been described as a sense of impending doom,” said Dr. Andrew Kolodny, co-director of opioid policy research at the Heller School for Social Policy and Management. Kolodny, who was not involved with the study, said it was important to show that patients on opioids could be weaned successfully, but it takes a lot of work.

“Getting patients off is not easy. The patients that were able to get off needed lots of visits and multidisciplinary care,” he said.

And getting that care can be difficult, said Dr. Steven Stanos, president of the American Academy of Pain Medicine.

“You need to have the resources to do this. Articles like this show we need to have greater access to behavioral health, interdisciplinary programs,” he said.

He said some physicians don’t have any choice but to prescribe opioids because they don’t have access to these kind of therapies. He hopes that studies like this can help convince insurance companies that it is important to cover these types of treatments.

Join the conversation

“If all you can get is medication, your pain management options are pretty limited,” Krebs said.

But she also cautioned that this isn’t a one-size-fits-all prescription for pain management – and there may be people for whom non-opioid therapies aren’t effective.

“The opioid epidemic started in a large part as a response to conversations about pain. People need access to effective treatments for pain,” Krebs said. Treatments are “low-tech: It’s support for physical therapy, occupational therapy, nurses, physicians and all kinds of clinicians. It’s not one drug or another. It’s just really important as we think of access to treatments. People need a variety of approaches to pain.”