Editor’s Note: This CNN Travel series is, or was, sponsored by the country it highlights. CNN retains full editorial control over subject matter, reporting and frequency of the articles and videos within the sponsorship, in compliance with?our policy.

Hokkaido, Japan’s northernmost main island, is unlike anywhere else in the country.

Fully annexed by Japan around 150 years ago, Hokkaido’s indigenous people, the Ainu, have their own distinct language and culture.

Much of the island’s landscape is unspoiled, filled with volcanic lakes, natural hot springs and mountain forests where brown bears roam wild.

In winter, the lush terrain is transformed, as average temperatures drop below freezing and the island is blanketed in meters of powder snowfall.

This unique climate has put Hokkaido on the map as a world-class destination for skiing and snowboarding. But the island is gaining a reputation internationally for its food too.

Chef Tomoyuki Takao grew up in this winter wonderland and has long understood its gastronomic potential.

“I was a boy who enjoyed skiing, playing in the park and running in the woods,” he says. “I became more and more interested in the wild vegetables and trees of the forest, which leads me to what I do now.”

Takao opened his eponymous restaurant in Sapporo, the prefecture’s capital, in 2015. Two years later, Takao was given its first Michelin star,?one of 77 restaurants to receive at least one star in the most recent version of the French brand’s Hokkaido guide.

But visitors won’t find traditional Japanese cuisine here. The chef serves Italian dishes, inspired by the European nation’s regional cuisines, which make the most of seasonal local flavors.

“I wanted to express the beauty of Hokkaido’s ingredients,” Takao says. “I realized that Italian cuisine would be more suitable.”

He sources almost entirely from Hokkaido’s three landscapes: forests, fields and oceans. Facing bitter wind chills, blizzards and the risk of encountering a passing bear, this can be a challenge in the winter. But Takao believes these efforts make the rewards all the sweeter, especially when it comes to seafood.

“Products in winter are rich,” he says. “I think this is something unique to the cold weather in Hokkaido.”

Cooking the forest

Spanning over five and a half million hectares, Hokkaido’s forests are a treasure trove of potential ingredients. In winter, Takao heads to a forest near his home in Sapporo around twice a week to forage for plants, such as bamboo leaves and white birch bark. He then takes them to the restaurant or his home laboratory to ferment, distill or roast for later recipes.

“I’m cooking the forest, so to speak,” Takao says.

The chef leans on centuries of Ainu wisdom in making food last over long winters. Joining them on a foraging trip in 2015, he learned to find lesser-known plant species and traditional ways to preserve them.

“I realized that the indigenous Ainu people were the most knowledgeable about the forest,” Takao says.

This experience inspired Takao’s signature turep pasta with a ragu of venison tongue and wild birch bark. Turep is the bulb of a giant lily native to the forests of Hokkaido and northern Honshu, traditionally used by the Ainu as a source of starch. The deer meat is sourced from local hunters, utilizing a cut that’s often thrown away, and is simmered with Takao’s foraged bark in a red wine sauce.

Championing values like wild foraging and zero waste, dishes like these have helped Takao stand out in Hokkaido’s fine dining scene.

“People said it was a little strange at first,” says local food journalist Sonoko Fukae, explaining that Takao’s approach “didn’t fit with the uniquely Japanese notions of meticulousness and luxury.”

“I used to think that it was fantastic to use ingredients like truffles or foie gras,” Takao says. “I’ve come to realize that there is tremendous value in things that are close at hand, right under our feet.”

This philosophy even extends to the items Takao serves his food on. He sources restaurant tableware from Mikasa-based wood artisan Yu Uchida, who crafts his pieces by hand from Hokkaido timber.

Uchida makes the most of the wood’s natural characteristics in his designs, saying he can see the seasons’ impact on the forest in the woodwork.

“In wintertime, the regrowth inside a damaged tree creates a uniquely attractive wood grain that I find really fascinating,” Uchida says.

Find out more about how Takao serves up a forest feast in the video above.

Reaping the field’s rewards

Hokkaido’s fields may be at their most vivid in the summer, when the island’s colorful flower gardens are in bloom, such as the rolling hills of Shikisai-no-oka. But in winter, one distinctive weather phenomenon dominates this landscape.

Japan powder, or “japow,” occurs when steam rises from the warm waters of the Sea of Japan and is cooled by Siberian winds, forming clouds. The clouds collide with hillsides, producing some of the softest and lightest?snow on earth – and lots of it.

Japow isn’t just good for covering ski slopes. Takahiko Soga says it’s crucial for his winemaking. Produced in Yoichi, Hokkaido’s burgeoning wine country, Soga’s Nana-Tsu-Mori pinot noir has earned global acclaim, going for hundreds of dollars a bottle. It was the first Japanese wine ever served in the iconic restaurant Noma in Copenhagen, and is a firm favorite on Takao’s wine list.

“It’s a wine that is distinctly Japanese,” says Takao. “I’ve never had a wine like it.”

Burgundy in France is historically famous for pinot noir. But climate change is threatening to push temperatures above the ideal range for cultivating the grape variety. Meanwhile, Yoichi’s climate is warming into one “very favorable for Pinot Noir,” Takahiko says, making growing the grapes “easier and more stable.”

The meters of powder snowfall each winter are an added advantage. The light, dry japow insulates the vines from frost and wind without freezing them, Soga says. “The vines can stay hidden under the snow all winter long.”

Hokkaido’s volcanic soil and soft water help create a unique terroir, which Soga aims to highlight with natural fermentation techniques.

“Fermentation produces an umami flavor,” Soga says. “It is easy to mix and blend with our Japanese food culture.”

In Ebetsu, another of Takao’s suppliers makes the most of the environment too. Ambitious Farm, founded by Akio Kashiwamura, preserves cabbages under the snow.

“In the fall, we harvest the cabbages that have grown really big, and line them up just before the snow falls,” Kashiwamura says.

The practice, known as overwintering, is traditionally used in Hokkaido to make vegetables sweeter and “deeply delicious,” adds Takao.

“The sugar content slowly rises when they are left to rest in the snow at just the right temperature of zero degrees Celsius.”

But climate change is making farming harder – Kashiwamura was only able to harvest one-tenth of the cabbages he planted. Extra steps like overwintering are “labor-intensive”, Kashiwamura says, taking up valuable time and effort.

“And cabbage, on the other hand, doesn’t get that expensive,” the farmer says. “We just want to preserve the traditional methods that have been practiced in Hokkaido.”

Find out how Takao supports these producers and more in the video above.

The ocean’s winter bounty

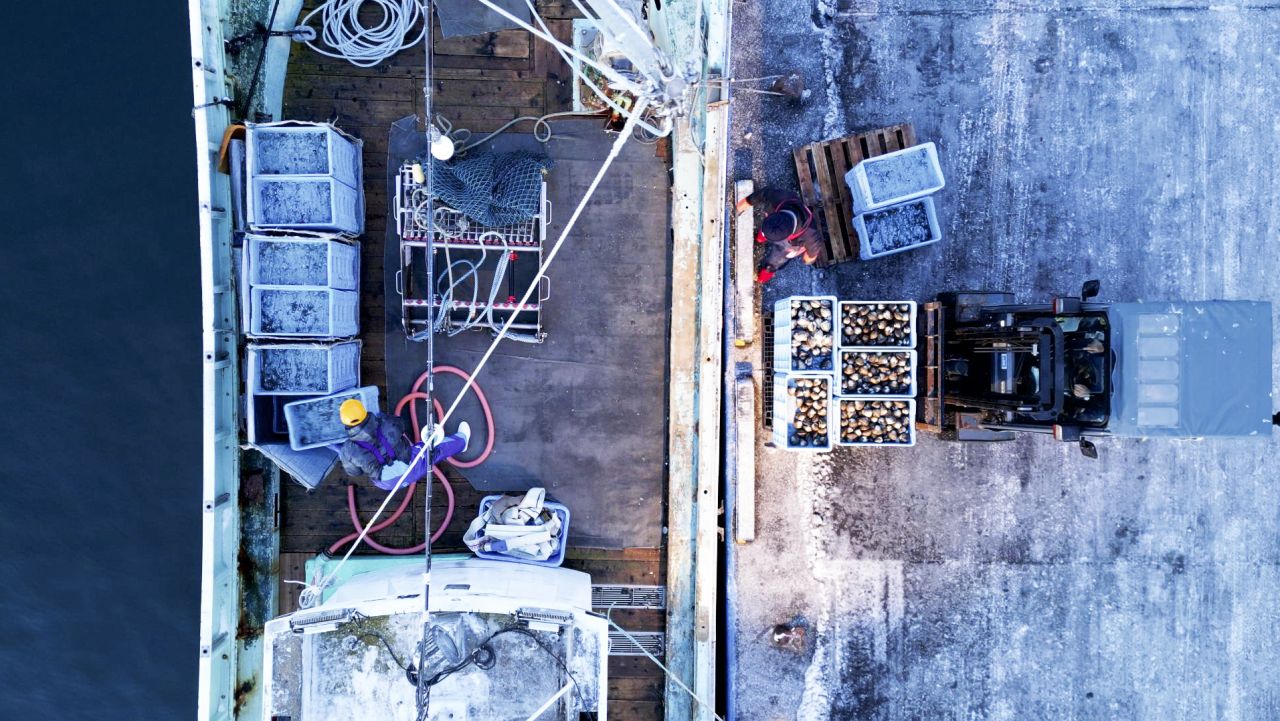

Seafood is an integral part of Hokkaido’s food culture. The island is surrounded by the Pacific Ocean, the Sea of Japan and the Sea of Okhotsk.

“They all have different currents and bring richness in the water,” says Hokkaido-born chef and presenter, Akemi Yokoyama.

“Because we are up north, we attract a lot of fish that are not really seen in the rest of Japan.”

Scallops are considered a particular delicacy in Hokkaido, and are often on Takao’s menu. In winter, the chef sources them from Notsuke, where they can weigh 500 grams per shell.

“They have a sweet taste … are very meaty and have a concentrated flavor component,” Takao says.

A number of marine species are best eaten in winter, locals say, when they store nutrients, preparing to lay eggs in the spring.

This includes hokkigai, or surf clams. Tomakomai, on Hokkaido’s Pacific coast, has the largest catch of hokkigai in Japan, around 800 tons a year, according to Kazuki Akazawa, the manager of Tomakomai’s Fishing Cooperative.

The clams vary in age when they are caught – from around five years old to 40. It is part of Tomakomai’s resource management plan, where fishers catch “less than 10%” of the total amount of hokkigai each year, says Akazawa.

“Catching that much still leaves the resource quite abundant.”

With temperatures dropping to negative double digits on the Celsius scale, fishing in mid-winter requires serious sustenance. Akazawa says “hokki” curry has become known as fishermen’s “soul food” in Tomakomai.

“They use hokki instead of meat because it is nutritious,” he says.

Tourists come from across Japan to try the hearty dish at portside café Marutomo Shokudo, where it’s served in heaped, steaming platefuls. When Takao visits, he savors every bite.

“I felt the splendor of the place and the richness of Hokkaido’s resources,” Takao says.

Find out how Takao puts a fine-dining spin on hokkigai in the video above.