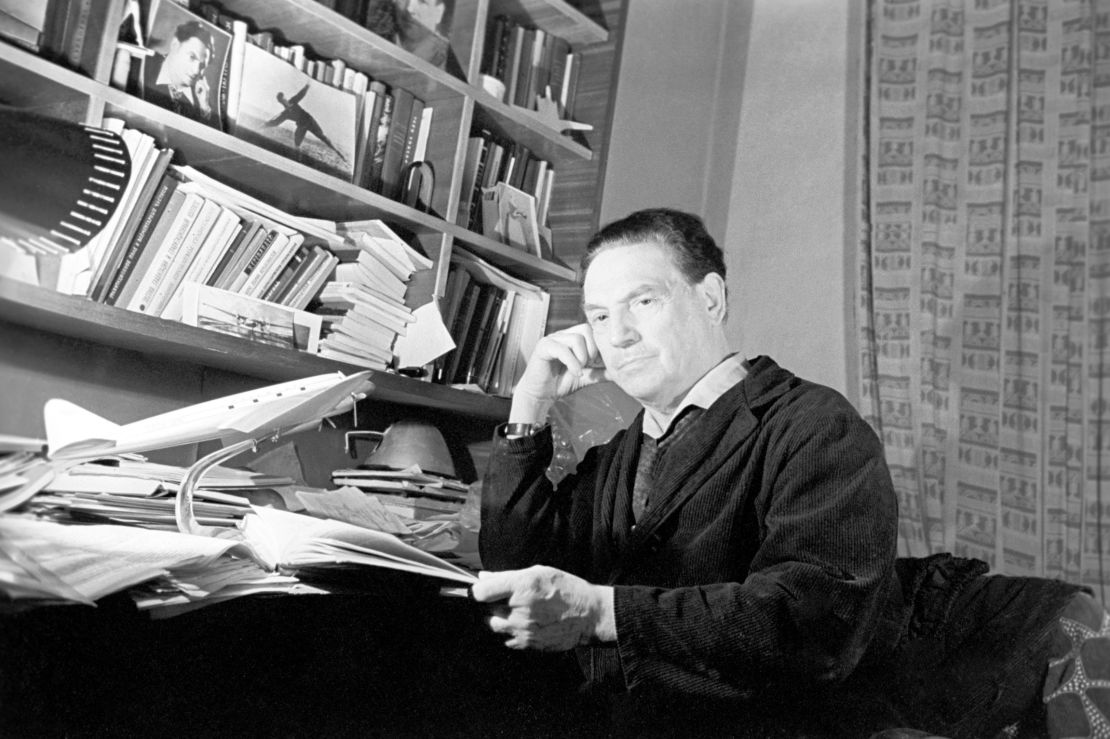

His life is such a mystery that even his real name is uncertain, but his legacy to the world of aviation is clear: Robert Oros di Bartini – as the inscription reads on his tombstone – was a genius ahead of his time whose wondrous airplanes and bizarre flying boats still impress today, almost 50 years after his death.

A modern polymath who spoke seven languages, he was also an astronomer, philosopher, physicist, painter and musician.

He spent his youth in Austria-Hungary and Italy, but he left his mark as an aircraft designer in the Soviet Union, sharing the stage with some legendary names in aviation history: Andrei Tupolev, Pavel Sukhoi and Oleg Antonov.

“As an innovator, he was at the same level as these, if not higher,” says Giuseppe Ciampaglia, author of “The Life and Planes of Roberto Bartini,” one of a handful of Bartini biographies and a rare one outside of Russia. “But because he wasn’t Russian,” Ciampaglia adds, “he didn’t achieve the same success.”

Bartini designed more than 60 aircraft, but only four ever flew, and just as prototypes. And even though he broke world records and influenced the design of many successful planes, he was hardly ever celebrated.

Instead, he spent almost a decade in a Soviet prison on suspicion of being a spy.

An early passion

According to Ciampaglia, many of Bartini’s biographical notes are unknown even to his daughter, who lives in Russia, and details of his early life are not backed by official records.

There is some consensus, however, on the fact that he was born in 1897 in Kanjiza, a small town in the Austro-Hungarian Empire – today in Serbia near the border with Hungary. He was born out of wedlock to a local 17-year-old noblewoman and a baron from the nearby town of Fiume, today in Croatia and called Rijeka.

Tragically, the woman died by suicide after her family gave the child up for adoption to bury the scandal, according to Ciampaglia. Three years later the baron, Ludovico Oros di Bartini, legitimized Roberto and then raised him as his own with his wife, passing on his noble name as well as his interest in the natural sciences.

Aged 15, Bartini attended an air show featuring a Russian pilot flying on a Beriot XI, one of the very first mass-produced airplanes. That was likely the seed of young Roberto’s passion for aviation, which he only had a short time to explore: in 1916, he was drafted into the Austro-Hungarian army and sent to the Eastern Front to fight against the Russian Empire in World War I.

Red Baron

Quickly captured, Bartini was sent as a prisoner of war to a camp in Siberia, where he became familiar with Communist literature and remained until the end of the war. Upon his release, he didn’t have enough money for the trip back home and spent some time in Shanghai as a taxi driver. He eventually made it back to Fiume, which was in a state of political turmoil following the dissolution of Austria-Hungary.

Eager to complete his studies, Bartini moved to Italy to attend aerospace engineering courses at Milan’s Polytechnic Institute, as well as a flight school near Rome. He already spoke perfect Italian, which wasn’t uncommon among residents of Fiume.

Using the name Roberto Orosdy, in 1921 he joined the nascent Italian Communist Party, where his familiarity with languages, weapons and aristocracy made him a promising intelligence officer. Within the ranks of the party he received his nickname, “Red Baron,” referencing his noble origins and the color traditionally associated with communism.

When Mussolini took power in late 1922 with a coup, however, Bartini became wanted by the police. To avoid his capture, the party sent him to the Soviet Union as an aviation engineer, putting his talent and Italy’s expertise in the field – at the time among the best in the world – at the service of the motherland.

The first prototype

In the USSR, Bartini changed his name again to Robert Ludvigovich Bartini, after his father Ludovico and following Slavic naming conventions. He first worked on experimental amphibious aircraft and then – after getting fired for criticizing the very organization that employed him – he was hired by the research wing of the Red Army.

Officially, Bartini was designing passenger planes. In reality, he was working on a monoplane fighter aircraft, the Stal-6, of which a single prototype was built – the first Bartini project to make the leap from the drawing board to the runway.

With a full stainless steel body and a single, retractable front wheel, it looked like something from the future, at a time when the materials of choice for aircraft construction were wood and fabric. Built for speed, it flew at 260 mph.

“At the time, in 1933, the speed record in the USSR was 170 mph, so it was almost 100 mph faster than the best Soviet fighters,” said Sergej Te?ak, a professor of transport engineering at the Maribor University in Slovenia. “It was a bit like if today someone built a fighter plane that flew at 2,400 mph, compared to our current fastest speeds of about 1,800 mph,” he adds.

Despite the record, the plane never entered production. Bartini designed an upgraded version with weapons in 1935, but concerns about the fragility of some of its unproven technical solutions, such as the evaporative engine cooling system, led to its rejection.

According to Te?ak, had this plane been built, the USSR would have had a superior fighter ready by 1941, in time for World War II.

World records

Bartini’s next aircraft, the Stal-7, was a twin-engine passenger plane.

“It was also made of stainless steel and very unusual,” says Te?ak. “Bartini had patented a new technique to weld the steel plates.”

Highly aerodynamic, it was shaped in a way that made it consume less fuel at high speeds. But in 1938, when an accident damaged the only Stal-7 prototype, Bartini himself was blamed. “He was arrested because he was believed to be Mussolini’s agent, and Stalin imprisoned him,” says Te?ak.

A year later, during a secret test flight, the repaired Stal-7 broke two world records by flying non-stop for 3,149 miles at an average speed of 250 mph.

“A formal reception was held, and when Stalin asked where the designer of the plane was, he was told he was in prison. Stalin quickly ordered to put him to work on new airplanes. This probably saved Bartini’s life,” says Te?ak.

Bartini’s sentence was reduced and he was sent to a sharaska, an informal name for the secret research and development laboratories in Soviet prisons in the 1940s and 1950s, which offered much better living conditions than the prisons themselves, according to Te?ak.

Delta wings

With World War II in full swing, Bartini worked on military aircraft only. He transformed his Stal-7 from a passenger plane to a high speed, long range bomber called the Yermolayev Yer-2, which was operated throughout the war. He also helped design the Tupolev Tu-2 bomber – a crucial asset in the Red Army’s arsenal – by working directly alongside Andrei Tupolev himself.

Bartini’s next project was the T-117, a heavy transport aircraft that was only partially built. Designed to transport tanks and other heavy military equipment, it had a distinctive loading ramp at the back, so that vehicles could drive into the plane. It was never finished due to a shortage of suitable engines, but many of its design elements are clearly visible in today’s super heavy transporters from Antonov, the leader in the field.

“The project was abandoned in 1946, but Bartini’s drawings were then sent to the Antonov company, which was the first to build a wide-body transport aircraft a decade later,” says Te?ak.

After his release from prison, in 1946, Bartini shifted his attention to supersonic aircraft. His drawings reveal that he had already figured out that delta-shaped wings – like those of Concorde – were necessary to fly faster than sound. “In aviation this is even sometimes called the Bartini wing,” says Ciampaglia.

To design these superfast airplanes, in 1954 he was given the first ever Soviet computer, the BESM1. The result was the fantastical A-57, a supersonic bomber capable of carrying nuclear weapons, landing on water and flying at 1,500 mph.

The Minister of Defense, former general Georgy Zhukov, liked the idea and gave Bartini an office and an apartment in Moscow to work on it. When he lost his post, however, the A-57 went with him and ballistic missiles were built instead.

According to Te?ak, the results of Bartini’s research were then sent to the Tupolev design bureau, which incorporated them into the Tu-144, the infamous Soviet clone of Concorde.

Ekranoplans

Bartini Beriev VVA-14: Photos of a Soviet prototype aircraft

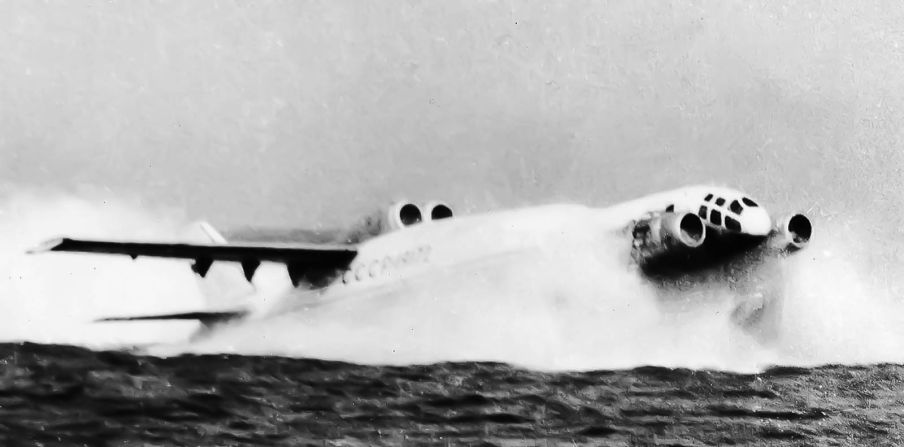

Bartini long held a fascination with flying boats and planes capable of landing on water; in 1934 he had built the DAR prototype, a twin-engine amphibious aircraft intended for Arctic reconnaissance. In the 1960s, however, he made seaplanes his main endeavour, with a focus on ekranoplans – planes that could fly very close to a water or land surface by exploiting a principle called ground effect.

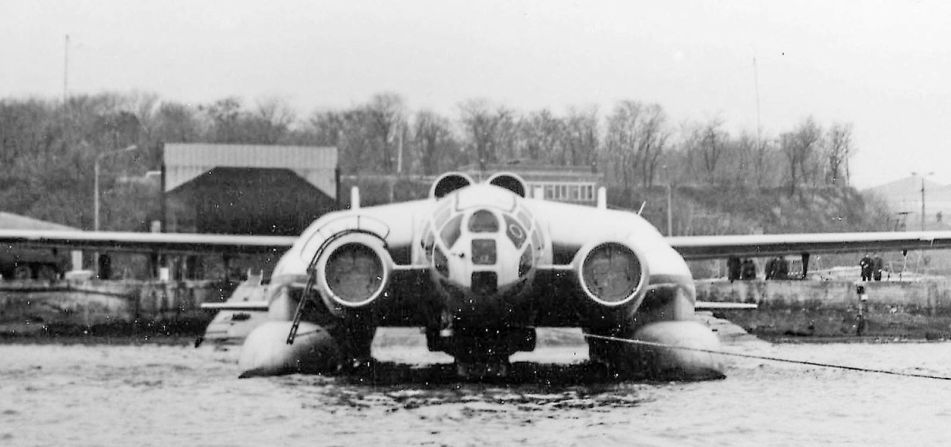

In 1972, fully rehabilitated and even the recipient of the Order of Lenin, the Soviet Union’s highest civilian order, he completed his most ambitious prototype, the Bartini-Beriev VVA-14. Designed to hunt and destroy US nuclear submarines, it was meant to take off vertically from anywhere – land, water, sand or ice – and then fly close to the surface at high speed.

“The VVA-14 is the only plane Bartini designed that he has seen fly,” says Te?ak. “He didn’t see the rest of them fly at all, because he was in jail most of the time. Eyewitnesses say he had tears in his eyes. This was just before his death.”

The original prototype performed more than 100 flights, but a second one was never completed because the engines for vertical takeoff actually didn’t exist.

Bartini tried to revive the project by turning the original VVA-14 into an ekranoplan, but he died before he could see the results of this work, in 1974.

The aircraft was tested well into the 1980s, but once the Cold War ended, there was little use for it. What’s left of the original prototype sits outdoors in a dilapidated state at the Central Air Force Museum near Moscow, with its wings missing.

The man and the myth

Bartini’s work went beyond airplanes. In 1965 he published a scientific paper titled “The relation between physical constants,” a new theory of the universe based on six dimensions. It was the culmination of his interest for physics and the natural sciences, which he tried to weave into his aviation projects too.

“At one point he wanted to build an invisible plane,” says Te?ak. “It would have worked by using vibrations in certain frequencies, similarly to how rotor blades from a helicopter become invisible once they start rotating. He thought he could apply that to a fuselage and planned to use the research he had done in the field of optics to do so.”

Sometimes referred to as the Nikola Tesla of his time, Bartini was an exuberant genius, which has led to some outlandish claims about his life.

One says that he was the inspiration for the aviator character in Saint-Exupéry’s classic novella “The Little Prince.” Another states that the story of his youth is entirely made up and that Bartini is an invented name, which he jokingly explained as a Latin acronym for “Bella Avis Rubra Terrorem Infert Nigra,” which translates to “In war, red birds terrorize black ones” – referencing the superiority of communist warplanes over fascist ones.

The epitaph on his tombstone in Vvedenskoye Cemetery, in Moscow, says something similar: “In the land of the Soviets, he kept his oath, devoting his whole life to making red planes fly faster than black ones.”

Before his death, he reportedly asked in his will that his papers be sealed away, only to be opened on the 300th anniversary of his birth – in 2197. Maybe, by then, we’ll have cracked all of Bartini’s mysteries.