Story highlights

Columbus discovered America -- and paprika

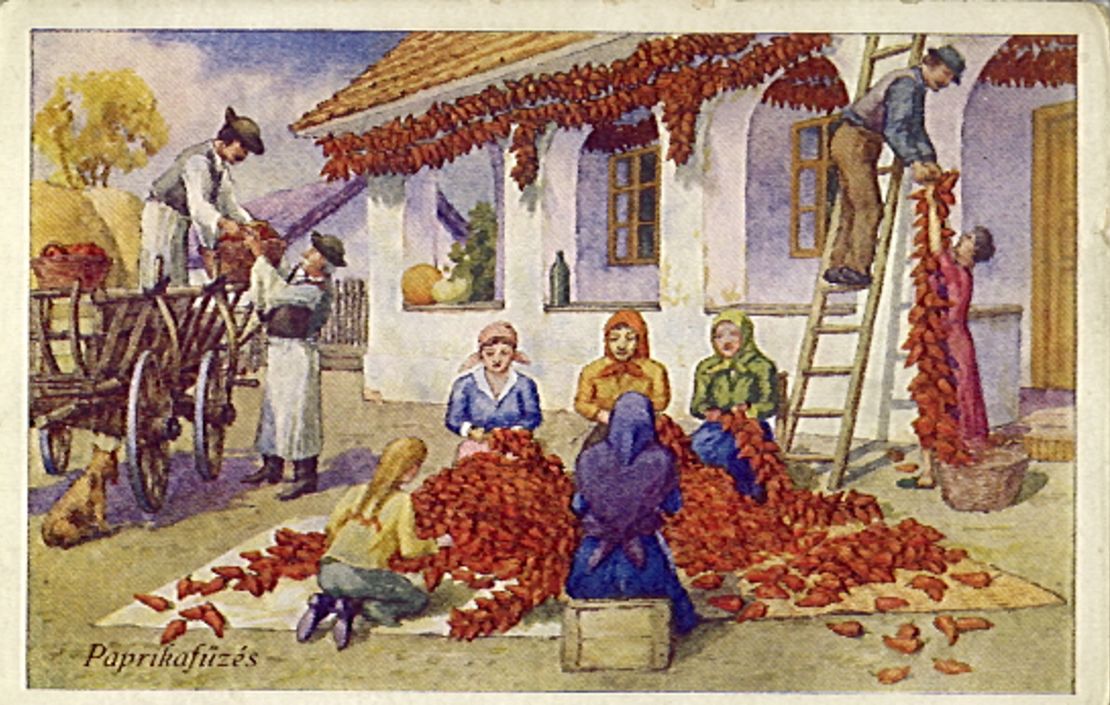

It's a spice but can be used in desserts

Not too long ago, you could be arrested for selling it

It’s as red as blood and, for the traditional Hungarian chef, no less essential for a healthy life.

But humble paprika – national spice and integral to all the most treasured Hungarian dishes – has been having a rough time.

Hungarian paprika production has slumped as buyers across the world have turned to cheaper supplies from Spain, China and Latin America.

And two years of unpredictable weather in Hungary may mean this year’s crop of capsicum annuum peppers – the raw ingredient of paprika – is the poorest in 50 years.

Horror of horrors, Hungary may even resort to importing the crop.

But despite these trials, and past upsets such as the communists nationalizing paprika production, the spice remains as crucial as ever to the Hungarian soul.

To understand Hungarians, you need to know a little bit about their favorite ingredient.

And if all else fails, this paprika primer will make for good talking points if you’re stuck in a Budapest goulash restaurant on a rainy afternoon.

1. It’s Mexican

Well, from around those parts, anyway.

Paprika peppers aren’t indigenous to Europe – the spice was among the treasures collected by Christopher Columbus on his expeditions around southern Mexico, Central America and the Antillies in the 15th century.

It made its way to Hungary via the Balkans a little later, where it was grown in the gardens of the aristocracy.

Its name is the diminutive of a Slavic word for pepper: “Papar.”

“We believe Columbus’s mission was a success because he came back to Europe with a marvelous spice,” says Gyula Vegh, of the Szeged Paprika Museum, in southern Hungary.

“He discovered America on the way.”

More: 11 things to know before visiting Hungary

2. There are two – yes, two – paprika museums

And two paprika festivals – one in the town of Kalocsa (Hungarian site only) and another in Szeged, which has been the center of the Hungarian paprika industry for more than a century.

And, no, Szeged doesn’t have a huge fiberglass paprika pepper on a pole just outside town.

The two museums are also both working production plants.

The Szeged Paprika Museum (Fels? Tisza-Part 10, Szeged 6721, Hungary; +36 20 980 8000) shares a building with the Pick Salami factory – visitors get three varieties of salami to taste and a 10 gram sampling of paprika.

Visitors to the Paprika Molnar (Hungarian site only) factory, in the village of Roszke, get a guided tour from the company’s CEO, Anita Molnar, as well as a spice sample.

“When people see how much work paprika-growing takes, they appreciate what they get in their little takeaway bag,” Molnar says.

Dried paprika peppers resemble red potato chips and can be eaten like that – they’re a big hit among kids visiting the Molnar factory.

3. Hungarian paprika is supersweet

It takes seven months, from seed to ground powder, to produce paprika.

Hungarian paprika peppers are sweeter than others because of the country’s cool growing season, which retains sugar in the spice.

The weather also affects the color of the paprika.

“In hotter regions such as Peru or western China, the sun makes the paprika dark red,” Molnar says.

“As the sugar content decreases, the red color is enhanced.”

But Hungarian paprika wasn’t always so sweet.

In the 1920s, the peppers were of such a hot variety they could only be used after the pith had been removed, typically by women workers.

“However, women with little babies couldn’t do the job because they’d have to touch the children afterward,” Molnar explains.

“So unmarried women, or those with older children, picked the peppers instead.”

More: Guide to Hungary’s signature dishes

4. It’s not just for goulash – try cake

Early last century, 830 workshops in Szeged alone processed peppers for paprika.

But after a Hungarian botanist cultivated a new – naturally sweet – variety, large-scale farming became possible and the artisans were replaced.

Hearty and cheap, the classic paprika-rich dish goulash was originally considered peasants’ food.

But paprika’s good for more than goulash: It’s liberally dispensed in the dishes served at Sotarto Halaszcsarda (Roosevelt tér 14, Szeged, Hungary; +36 62 555 980) fish restaurant in paprika central, Szeged.

In Budapest, the upmarket Zeller bistro (Izabella utca 36-38, Budapest 1077, Hungary; +36 30 651 0880) gets rave reviews for its wide range of paprika-rich offerings.

It sounds strange but Hungarian paprika’s also sweet enough to use in desserts.

“Even I didn’t know that paprika could be used for sweets and not only savory dishes,” says Lajos Kossar, a Hungarian food writer and chef.

“Then I tasted my grandmother’s paprika cake.”

5. The communists traded it for hard currency

After World War II, paprika production in Hungary was nationalized by the communist government.

Local growers were prohibited from milling their own paprika powder and had to hand over all their peppers to state-owned mills.

“The old lady who looked after me when I was a child was sent to prison for four months for being caught selling two kilos of paprika,” Molnar says.

“Paprika was strategic. Each year several thousand tonnes were exported for Deutschmarks or dollars.

“The communists needed the foreign currency.”

6. Paprika’s bursting with vitamin C

The Hungarian scientist Albert Szent-Gy?rgyi won the Nobel Prize in 1937 partly for the discovery of vitamin C. He also found a high vitamin C content in paprika peppers and learned to extract it.

Szent-Gy?rgyi sent vitamin C crystals from paprika peppers to parts of the world where people were suffering from scurvy.

More: Budapest’s best ‘ruin bars’

London-based journalist Howard Swains’s work has appeared in The Sunday Times Magazine, The Guardian and Wired, among other publications. He is the author of the “Spectacular Slovakia” travel guide.

CNN Travel’s series often carries sponsorship originating from the countries and regions we profile. However, CNN retains full editorial control over all of its reports. Read the policy.