No matter how you like your wiener prepared, grilled or boiled, with mustard, ketchup or chili, we can all agree on one thing, and that’s that hot dogs have become part of a certain American cultural narrative.

And this year, more than ever, hot dogs are red hot; in March, the data firm IRI reported that sales were up by as much as 127%, and that was well before grilling season started.

Billions of hot dogs

“Americans eat an estimated 7 billion hot dogs between Memorial Day and Labor Day,” Eric Mittenthal, president of the National Hot Dog and Sausage Council, said.

But while hot dogs may feel “all-American,” they’re inherently something else.

Also known as the frankfurter, this specific style of cased sausage was originally thought to be from the town of Frankfurt-am-Main in Germany, but hot dog historians argue that sausage culture, native to Eastern Europe and, particularly, Germany, has no specific town of origin.

The traditional German hot dog, when it arrived in the United States, was a blend of both pork and beef; the all-beef hot dog, as we now know it, takes its roots from Jewish-American butchers, who, due to Kosher restrictions, chose not to use pork in their meat blends.

“When Germans came, you have to look at where they came from,” said Dr. Bruce Kraig, professor emeritus at Roosevelt University in Chicago.

Kraig is a hot dog historian and the author of several books, including ‘Hot Dog: A Global History’ and ‘A Rich and Fertile Land: A History of Food in America.’

“A good number of the early [Germans] came from the Palatines,” which is a general area surrounding the actual city of Frankfurt, explains Kraig. Frankfurt, Kraig said, refers to the region of origin, though the actual food does not necessarily come from Frankfurt itself.

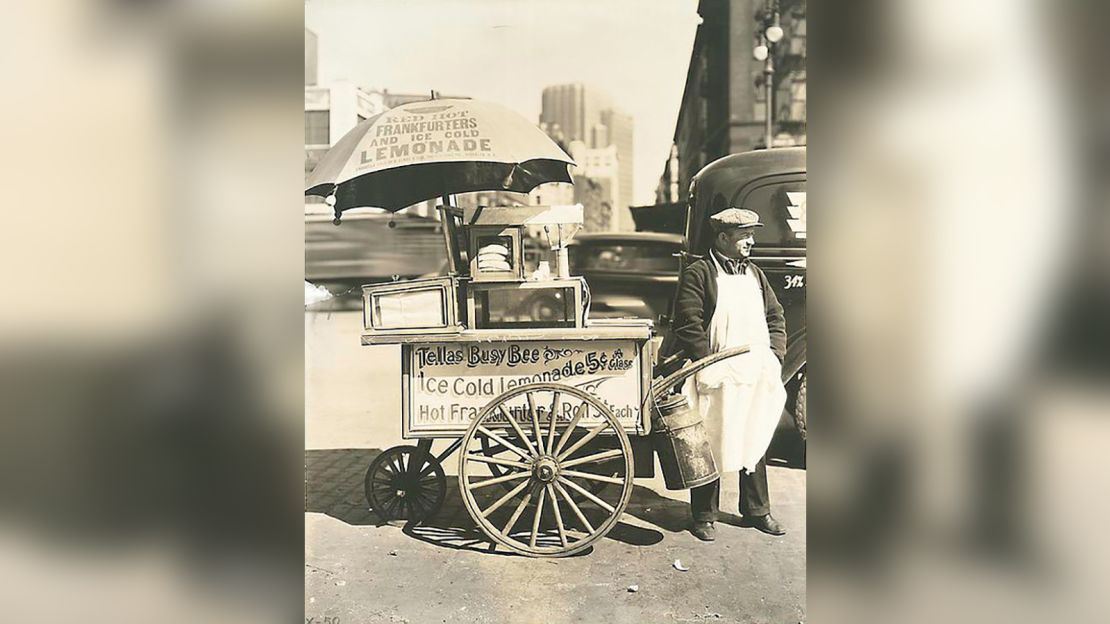

Brought over by German immigrants in the mid-1800s, hot dogs began their path into the American zeitgeist in New York City hot dog carts, where they were a natural fit for the sandwich-loving harried New Yorker, who already preferred to eat on the go.

“They appear with the first German immigrants in the late 1840s,” Kraig said.

“Germans have sausage culture, so they eat sausage from butcher shops. They eat them at home. They eat them in the street at fairs and festivals, and at beer gardens, so when Germans got to America, they set up beer gardens right away.”

Classic street eats

Americans, he said, became enamored with the German idea of sausage eating on the street. “You have lots of evidence of sausage being sold by vendors, probably in the 1840s, but certainly by the 1860s. Wherever there are Germans, there are sausages sold in the streets.”

That plural is important, actually. Germany is not known for a single sausage, after all, but for its abundance of them, from the veal- and poultry-based weisswurst to the pork-based bratwurst to the jerky-like landj?ger.

German sausages are so plentiful that it’s remarkable that Americans inherited only one in the common dietary canon.

In 1867, an entrepreneurial baker from Brooklyn by the name of Charles Feltman began selling hot dogs from a converted pie cart on Coney Island. “Coney Island started becoming a spot that people would go for recreation, but there wasn’t really anything there at the time,” said Michael Quinn, co-owner of hot dog brand Feltman’s of Coney Island, which he and his brother, Joe Quinn, purchased in 2015.

Birth of the bun

Charles Feltman developed a hand-sliced, elongated bun that set the precedent for the modern hot dog bun.

When popularity surged — Michael Quinn, himself a Coney Island historian, said that, in that first summer, the cart sold about 4,000 hot dogs — Feltman set his sights higher, entering into a restaurant and hotel partnership and opening a sprawling resort in Coney Island in 1873.

“Eventually, it became billed as the largest restaurant in the world,” Michael Quinn said.

Numerous historic sources, including the Coney Island History Project, have acknowledged that, by the 1920s, Feltman’s Ocean Pavilion restaurant was serving roughly five million customers per year, and selling somewhere around 40,000 hot dogs a day.

Suddenly, hot dogs were on the national stage, and Coney Island was became the accessible epicenter of summer fun for anyone and everyone in and around New York.

Coney Island

That stage had already started to expand when, in 1875, Charles Feltman convinced president of the Prospect Park Railroad Andrew Culver to run the subway line down to Coney Island, offering public transportation to thousands of New Yorkers who had never before had access to the far reaches of Brooklyn.

The conflation of the subway line with Feltman’s massive resort made Coney Island important — and hot dogs were in the center of this major cultural moment.

Although Feltman’s empire diminished over time, and Coney Island became known less for its ritzy resort caché and more for its boardwalk kitsch, Feltman had already unknowingly contributed the greatest icon to American hot dog culture, when he hired a bun-slicer who would go on to become among the United States’ most famous hot dog vendors.

“They didn’t have machines back then, so one of the bun-slicers that the Feltman family hired was Nathan Handwerker,” Michael Quinn said. “He worked as Feltman’s as a bun-slicer!”

That same Nathan Handwerker would open his own competing brand, Nathan’s Famous Hot Dogs, in 1916, and that brand would become synonymous with Coney Island hot dogs.

In some ways, Nathan’s hot dogs now define the Fourth of July, which is when the famous Nathan’s Hot Dog-Eating Contest takes place each summer. Hot dogs helped to frame the fame of Coney Island.

“They were such an incredible sensation that Charles Feltman ultimately built a nearly 100-year empire on them,” said Feltman’s of Coney Island co-owner Joe Quinn.

How do you take it?

New York, of course, was not the only place where hot dogs took root in the late 19th century. “Hot dogs were spread around the country as immigrants spread to different regions,” said Eric Mittenthal. “The Chicago-style hot dog took hold during the Depression, when stands would offer a variety of toppings that people would pile onto the hot dog, though Chicago is not alone in offering distinctive dogs.”

While toppings differentiate dogs from place to place, one constant is affordability. A hot dog is a food of access. It is delicious, filling and cheap, no matter where you might find yourself, what city you happen to find yourself in, and that makes it appealing to anyone, irrespective of physical location. (Even vegetarians and vegans can enjoy hot dogs now — albeit of the meat-free likes of Beyond Meats and other brands on the market.)

German immigrants spread their love for sausages to other cities through the United States: Detroit, Milwaukee, and, later, Los Angeles.

Where Germans went, hot dogs followed. New Yorkers, of course, will argue that the specificity of the hot dog — a food that’s well suited to eating while moving — works particularly well in their city, which is why the association is one that resounds, over a century later.

“The advantage of having a hot sausage on an elongated bun — it’s a very New York thing,” Michael Quinn said. “New Yorkers like to walk and eat.”

As for the name, hot dogs were first coined “red hots” — a term that’s still used in both Maine and Detroit — sometime around the late 1800s, because of the heat of the grill that was used to cook them. But the dog part was really just cheekiness. “Hot dog is a joke word,” Kraig said.

The earliest he has been able to trace the word is to 1892, to a newspaper clipping hailing from Patterson, New Jersey. “The identification of sausages with dogs is considerably earlier,” he conceded.

According to Kraig, a popular song in the 1800s, written by Septimus Winner, begged the question: ‘Where, Oh Where Has My Little Dog Gone?’, allegedly a reference to a dog gone missing in sausage meat. Thankfully, in the age of transparency, we know that the hot dogs we eat today — 7 billion this summer, if not more — are all hot, no dog.

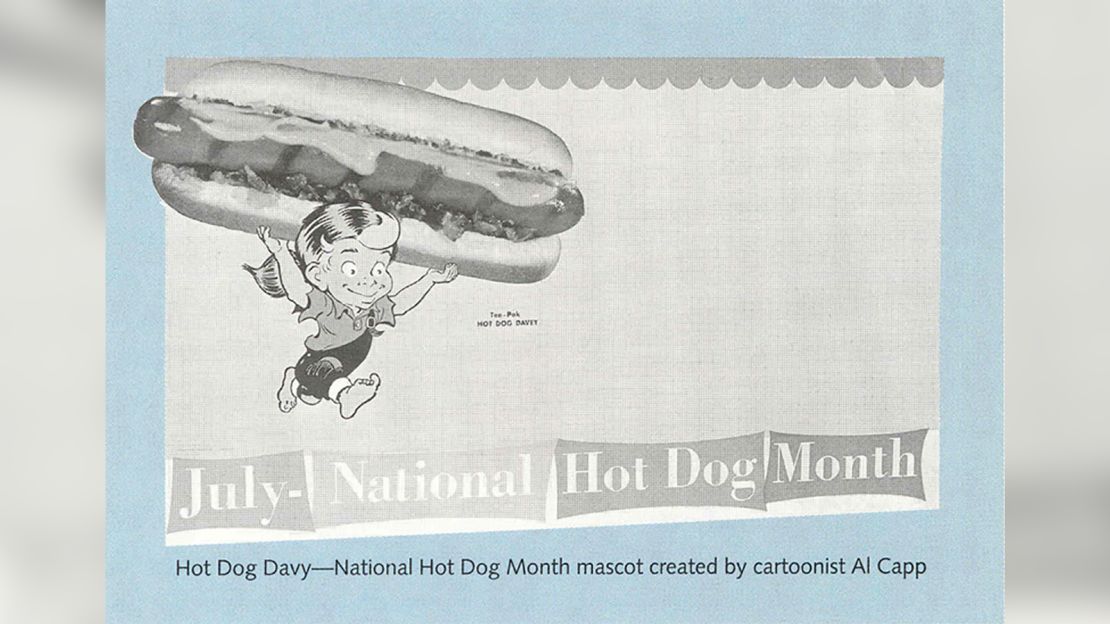

That’s a bit of a relief, for those looking to celebrate National Hot Dog Month in July. Break out the mustard.