Australia’s Great Barrier Reef seems indestructible from afar: Its 2,600-kilometer-long clusters of corals are even visible from outer space.

But on closer examination, the story loses some of its beauty. The reef – along with the multibillion dollar tourist industry it supports – could be extinct by 2050.

That is what some scientists are warning will happen if nothing is done to halt the impact of human-induced climate change.

Rising levels of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere are causing oceans to warm, they argue, bleaching the reef’s corals to death.

“Most coral reefs have been seriously diminished already,” says Charlie Veron, former chief scientist of the Australian Institute of Marine Science and author of the three-volume, “Corals of the World.”

“Today’s children are almost certain to see the Great Barrier Reef trashed within their lifetime.”

What is coral bleaching?

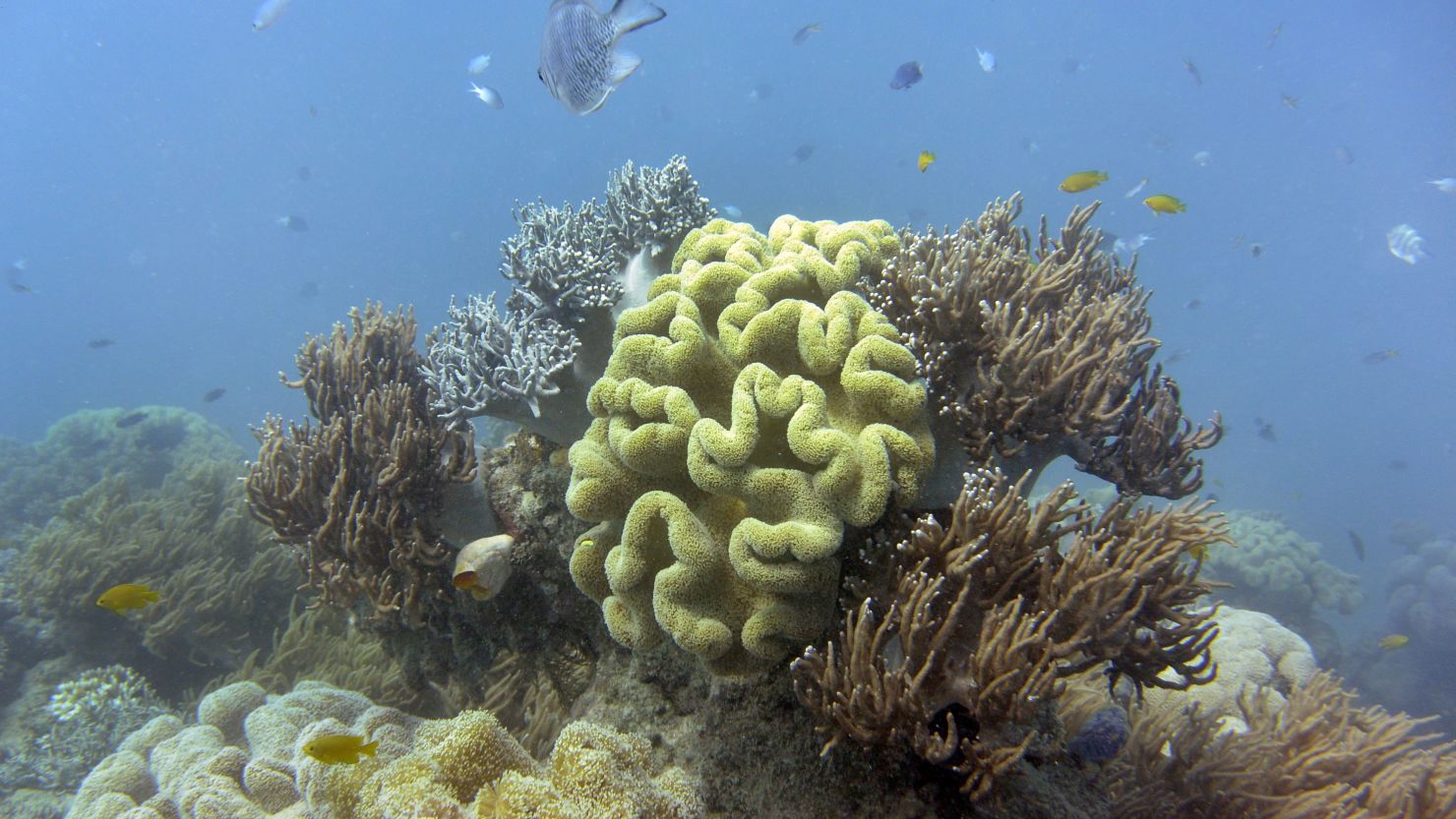

Coral bleaching occurs when corals, stressed by warming water, expel the symbiotic algae, which provide necessary nutrients. As a result, they turn colorless and their calcium skeletons get exposed. Unless the water cools, death is not far behind.

Today, over 90% of the Great Barrier Reef shows evidence of bleaching following a 2016 heatwave that saw sea temperatures in Australia reach record levels, triggering the most damaging and widespread coral bleaching event on record, according to a paper published in the journal Nature in March.

A further bleaching event this year, which followed on directly from last year’s has accelerated the damage and left no time for reef recovery.

Great Barrier Reef suffering ‘unprecedented’ damage

Bleaching has been observed on the Great Barrier Reef since 1982, with severe “bleaching events” occurring during the El Ni?o of 1997-98 and later in 2002 and 2006. During the 2002 episode, it was reported that bleaching affected more than 50% of the reefs, with 5% permanently damaged.

“As time goes on and carbon dioxide increases, the likelihood of mass bleaching goes ever higher,” says Veron. “There is no rate as such, just an ever-increasing probability.”

But that’s not the only big threat. Increases in carbon dioxide decreases the ocean’s pH, which causes acidification and has devastating consequences for the skeleton-building corals as well as marine life, Veron adds.

Planning for the reef’s future

Considered one of the seven natural wonders of the world and listed as a UNESCO World Heritage site, the reef is home to one-third of the world’s soft corals – as well as more than 1,500 species of fish and six of the world’s seven marine sea turtle species.

“Coral reefs harbor at least a quarter of the ocean’s biodiversity – if these fail, there will be a domino effect to most other ecosystems and the outcome could well be a mass extinction,” says Veron. “The only thing that will save coral reefs is to drastically slow the rate of increase of atmospheric carbon dioxide.”

The Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority (GBRMPA), the government agency that manages the reef, takes a similar view on the threats.

In its 2014 Outlook Report, it identified a number of key risks affecting the reef, the most serious of which is climate change. The others are continued declining water quality from catchment run-off, loss of coastal habitats from coastal development and impacts from fishing.

In 2015, the Australian and Queensland governments released a grand framework for protecting and managing the reef until 2050. They said one of the main goals of the Reef 2050 Long-Term Sustainability Plan is to make the reef more resilient to climate change and announced investment of $1.5 billion (AUS $2 billion) over 10 years.

“The reef is undoubtedly facing challenges,” says a GBRMPA spokesperson. “But it is in a better position than most other coral reef ecosystems around the world as management strategies employed over the past 30 years have been instrumental in helping strengthen the reef’s resilience.”

Earlier this year, UNESCO expressed “serious concern” about the back-to-back coral bleaching events that affected the reef in 2016 and 2107 and warned that Australia needed to accelerate its efforts on improving water quality to meet 2050 Sustainability Plan targets.

Industries and livelihoods also at risk

Climate change is not only threatening the reef’s fragile ecosystem, it’s also putting at risk the livelihoods of industries and communities that depend on it.

The marine park authority estimates that the Great Barrier Reef Park contributes about $5.76 billion (AU$7.55 billion) a year to the Australian economy, mostly through tourism and recreational fishing.

But while some scientists fear the worst, it appears their dire predictions over the reef’s future have yet to put a dent in the tourism industry.

About 2.8 million people visited the marine park in 2016, according to the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park authority.

“There is no evidence that visitor numbers to the (area) are currently being affected by perceptions that the reef is under threat,” said a Tourism Queensland spokesperson.

“(We) have long marketed the Great Barrier Reef as one of our major natural attractions that visitors from around the world can experience. We will continue our marketing focus along these lines.”

Even so, a number of operators admit they are worried about what the future holds.

Husband-and-wife duo, Brenda and Alan Irving, have been operating their scuba diving business, the Whitsunday Dive Centre, in the Whitsunday and Cairns regions of north Queensland since the late 1970s.

They’ve tried to weigh up the differing views on the reef’s long-term health, and what it means for their family business.

“I really don’t know what to think,” Brenda Irving says. “Obviously my business would cease to exist (if the reef became extinct). The number of people wanting to learn how to dive would diminish to the point where only one or two operators would remain.”

At present, however, she remains philosophical. “I’ve survived some pretty catastrophic events in the past, and I dare say that I’ll survive some in the future.”

Quicksilver Group – considered the largest Great Barrier Reef cruise company in the region operating out of Port Douglas and Cairns – said it was also taking the climate change threat very seriously.

“We are very concerned and are doing everything we can to reduce our carbon footprint and remove stress from the reefs we visit,” says Quicksilver Group’s environment and compliance manager, Dougie Baird.

Even so, scuba-diving fanatics David and Leyah Namoff, from Miami, aren’t taking their chances. They have always dreamed of diving Great Barrier Reef since they earned their diving certification in the 1970s. They’re getting ready to travel to Australia this month to dive off the reef.

“As a diver, it makes me sad to see the destruction of a reef that has existed for centuries, if not longer,” says David Namoff. “It makes me anxious to see the Great Barrier Reef before this occurs.”

The best tourist attractions that no longer exist

Editor’s note: This article was previously published in 2011. It was updated, reformatted and republished in 2017.