I knew Frank Lloyd Wright’s name before I knew anything about his work.

Maybe it was from the worst Simon & Garfunkel song ever. Maybe it was just a name thrown around in art class under the rubric of “Person You Should Have Heard Of By Now.”

But when I finally did discover Wright’s work, it was by accident – a trip to the Guggenheim Museum in New York City.

Stunned by the building as much as the art inside it, I looked up the name of the architect only to find a very familiar set of names – Frank Lloyd Wright.

For most Americans, Wright’s name is associated with houses. He believed that quality design could be affordable, that people should live in harmony with nature instead of closed off from it, and that you didn’t need a lot of space to live comfortably – all, to my ear, very American ideas.

This June, Wright fans around the world will celebrate the 150th anniversary of the architect’s birth, with New York’s Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) kicking off an exhibit dedicated to his life and work on June 12.

But my own personal journey into Wright sent me to the Midwest, where he was born and where many of his most singular designs still stand.

Wisconsin

Wright was born in Spring Green, Wisconsin, to a mother of Welsh heritage. He honored that heritage in the name of his home and studio there, Taliesin, (tally-essen), which is Welsh for “shining brow.”

Like many icons, Wright was as well-known for his life as for his work. He was known for his scandalous relationships with women and for often having financial problems, refusing to pay bar tabs or going wildly over budget on building projects.

Arguably the most controversial was “The Taliesin Murders,” when a disgruntled employee set fire to the Wisconsin estate, resulting in the death of, among others, “Mamah” Borthwick Cheney, the woman for whom Wright had left his wife of 20 years.

Today, the murders aren’t part of the typical Taliesin tour – although guides will answer questions if asked directly, and some will show you a charred section of the roof that was singed in the fire and never replaced – but they remain a key part of Wright’s mythology.

However, it was a more recent cultural reference that crossed my mind: All I could think about was the recent death of Taliesin Myrddin Namkai-Meche, the young man in Portland who defended two young Muslim girls from an attacker and was killed in the process – was he named for Wright’s famous home? And if so, what kind of awful symbolism was this?

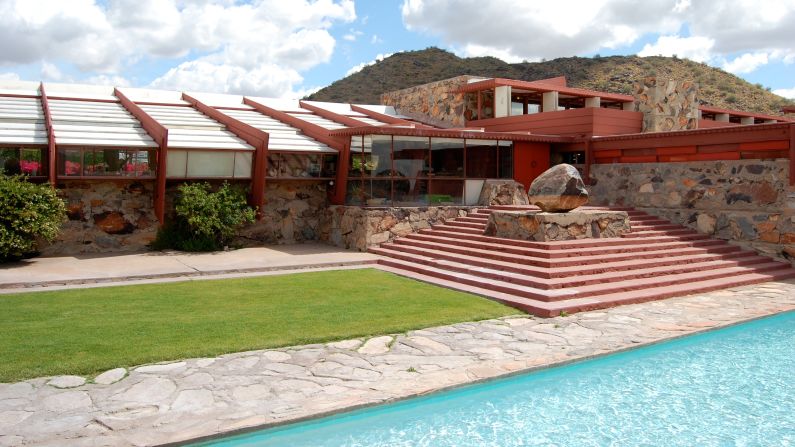

Taliesin is a great place to get introduced to some of the signature elements of Wright’s style, which will begin to feel familiar once you’ve seen a few of his structures – long straight beams, short ceilings that give way to larger open spaces, outdoor elements like plants brought indoors, heavy emphasis on natural light, and a major lack of storage space.

(Wright was known for hating basements and closets, as he believed that if he gave people room to store stuff, they would buy more stuff. Think of it as forced minimalism.)

Visiting Taliesin could easily fill an entire day – there are multiple buildings on the compound, including a school, and the grounds are expansive.

But Wisconsin had so many other riches – and just opened up an official Frank Lloyd Wright trail this year – I had to keep moving.

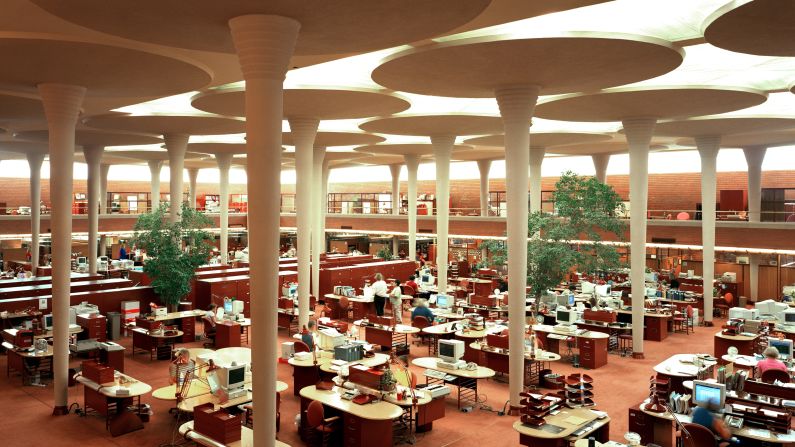

Within a single day, I saw several of Wright’s most notable buildings: the offices for the SC Johnson complex in Racine (where Wright cleverly integrated building materials like glass tubes, and where he built a dumbwaiter so scientists could send each other things from different floors), and sweeping Wingspread (which began as a home for Johnson’s then-president and is now used as event space).

The office, done in Wright’s trademark dusty “Cherokee red” hue and with chairs and other furniture designed by the man himself – he loved the idea of having full creative control, even though he had never formally studied carpentry– gives off a major “Mad Men” vibe.

Despite Wright’s international fame, not every building is as well-maintained as Taliesin or SC Johnson. Many have fallen into disrepair, cared for only by a committed team of local Wright fans and preservationists. One such example is the “Burnham Houses,” named because they occupy a full block of houses on Milwaukee’s Burnham Street.

The Burnham homes include duplexes – a curious anomaly, as Wright was best known for single-family homes – and are being purchased and fixed up one by one by the Wright in Wisconsin group. They’re of particular interest to Wright fans, as it’s the only time he designed multiple buildings on the same street.

Like many Wright groups around the country and the world, Wright in Wisconsin is hoping that the surge of interest around the 150th will bring in additional funds and support for their work.

Another such project is the AD German Warehouse, whose volunteer docent wagers it is the least-visisted Wright site in the world. The warehouse had fallen into disuse, and some locals – who still resent Wright or have a story about a bar tab he ran out on and never paid – wanted to tear it down.

Preservationists won out, though, and now a group of local volunteers have even gone so far as to hire experts in Hazmat suits to clean years’ worth of animal and bird feces out of the building. Now, there’s a small gift shop, the occasional guided tour, and the happy discovery of Wright artifacts from a retrospective of his work the architect put together in Italy.

The next day, it was on to Wisconsin’s capital of Madison, where one of Wright’s most enduring designs was not completed until after his death – Monona Terrace, a community center and event space – and he designed a project with special personal meaning, the First Unitarian Society Meeting House, which was a church whose founders included his parents.

As a designer of public places, it seems fitting that Wright’s designs would evolve over time. Monona hosts weddings and high school proms, while the First Unitarian Society shares its space with a local synagogue.

Iowa

Although Wright designed several hotels in his lifetime – including the now-demolished Imperial Hotel in Tokyo, which began his longtime appreciation for Japanese design – the only one still standing is the Historic Park Inn in the small town of Mason City, Iowa.

(There’s some debate about this – Wright had a major role in Arizona’s Biltmore Hotel, but was not listed as the architect of record.)

Wright was commissioned to design a law office and a hotel in Mason City, which have since been combined into one single building – it’s probably the only hotel in the world that also contains a legal library.

The town, whose other claim to fame is inspiring the setting of River City in Meredith Wilson’s musical “The Music Man,” might not otherwise be on the radar of international tourists, but thanks to its Wright connection travelers regularly visit from as far away as Germany and Brazil.

And while some Wright buildings get a reputation for being uncomfortable to live in – remember that thing about him hating closets – the hotel has been modernized with conveniences like Wi-Fi and TV without destroying the original design, and, don’t worry, the beds are delightfully cozy.

Because of Mason City’s remoteness – about 140 miles south of Minneapolis and 140 miles northwest of Cedar Rapids – many Wrightaholics combine their stay at the Park Inn with visits to Cedar Rock – a home Wright designed for the wealthy Walter family – and the Stockman House, a quintessential brown-and-white home in Mason City.

Although I only visited two US states, I was able to fit more than a dozen Wright properties onto my schedule – and that’s nothing compared to some of the other diehard Wright fans I met at Taliesin and elsewhere, some of whom have clocked more than a hundred homes and buildings so far.

But with Wright it’s not just about quantity, about crossing names off a list.

His work has helped me to understand some of what it means to be American.

Unlike many great architects of the past, Wright didn’t design ornate palaces or cathedrals – he made homes, many of which were in the range that a regular family (granted, a regular family with an appreciation for design and a willingness to put a piano in the living room even if they didn’t know how to play) could afford.

He made public spaces, like Monona Terrace, where people could take classes or interact with civic leaders.

When he designed servants’ quarters, they too were elegant– he believed that rich or poor, everyone deserved access to great design and to beauty.

Yes, his personal life had scandal. Yes, he could sometimes be a real pain to work with.

But his ideas continue on well beyond his life, and places from Manhattan to Mason City are studded with examples of his work – nearly everyone in the United States is within driving distance of something he created.

In a big, diverse, eclectic country like this one, it’s a rare feat – and an important one.