Toronzo Cannon has more energy before 5 a.m. than some people can muster all day.

“Hey now, you OK? You gonna be cool today?” he asks one co-worker at a Chicago bus garage. “How you doin’?” he asks another. “These guys right here owe me money, so take a picture of all of them,” he jokes.

Cannon, 49, has been a Chicago Transit Authority bus driver for 24 years. He’s also a blues musician whose career is on the upswing, and his near tirelessness is working in his favor.

Cannon drives 10-hour shifts Monday through Thursday, then jets off on weekends to play the Chicago blues across the country and around the world. He spends his vacation time playing back-to-back international dates.

The contrast of strolling by the Eiffel Tower and steering a bus through the streets of Chicago isn’t lost on Cannon. Yet his day job keeps him grounded, provides his family with health insurance and yields vivid material for songs.

The Eiffel Tower was “right down the street for the most part, and now I’m on the West Side of Chicago getting cursed out by some lady that’s short a quarter,” he said.

“I’m a bus driver, so I travel through several tax brackets. You know, I see from the poorest of the poor to the richest of the rich.”

“The Chicago Way,” Cannon’s latest album and his first on renowned blues label Alligator Records, chronicles the human stories that unfold on both jobs.

A few hours after he gets off work, Cannon will go from bus driver to bluesman, swapping his CTA hat for a dapper chapeau as he takes us to some of the blues clubs he came up in.

‘Everything is moving, everything is loud’

Raw and rhythmic, blues music was developed by African-Americans in the post-Civil War South, with an emphasis on vocals that tell the stories of everyday people, usually of men, women and the ups and downs between them.

Starting during World War I and spurred by oppression and economic hardship, millions of Southern blacks headed for cities in the North as part of the Great Migration. The music traveled with them, and Chicago eventually became the epicenter of urban blues.

The solo acoustic blues of the South gave way to band music featuring electric instruments and drums after World War II, creating a grittier, more aggressive sound.

Muddy Waters, Howlin’ Wolf, Little Walter and Jimmy Reed put Chicago blues on the map in that era, and by the 1960s the music had gained a worldwide audience.

“When blues got to Chicago, it got dirty. It got dirty from the electricity of the city,” Cannon said. “As you get to the big city where everything is fast, everything is moving, everything is loud, that does something to you,” Cannon said.

“Chicago blues is not background music. You know, you need to be heard, you need to be looked at. You’ve got something to say.”

Instant vacation: The world’s best travel photos

Buddy Guy’s Legends

At 88, “Bar Room Preacher” Jimmy Johnson has witnessed his share of Chicago’s electric city living.

As this night’s headliner at downtown South Loop club Buddy Guy’s Legends, Johnson puts his gospel-tinged voice to the blues’ central theme:

Learn to love me or leave me. Either one you wanna do

Learn to love me or leave me. Either one you wanna do

Because strange things are happening. Something strange might happen to you

Johnson belts out these lyrics at the glossiest club on our two-night blues hop, a spot opened in 1989 by Chicago blues legend Buddy Guy.

The spacious club’s walls are dotted with photos, instruments and other mementos of the famous and up-and-coming artists who’ve played its stage.

“Buddy Guy’s is the premier blues club in Chicago,” said Cannon. “You get a bunch of national acts to come through. He’s like the man now, when it comes to the blues.”

Guy, 80, is often spotted at the bar and sometimes steps in to play a few songs when he’s not on the road. He plays a series of formal dates at his club each January.

READ: In defense of being a tourist

Rosa’s Lounge

About 10 minutes from downtown on Chicago’s Near Northwest Side, Rosa’s Lounge in Logan Square has a cozier neighborhood feel. Most of the performers are from Chicago, although bands from all over the world come through.

Late blues greats David Honeyboy Edwards, Pinetop Perkins and Homesick James all played Rosa’s.

On a recent Friday evening, Chicago blues guitarist Melvin Taylor’s fiery playing had patrons moving to the music. One particularly energetic dancer launched himself across the floor in a series of riveting, whole-body spasms.

This is a friendly club where colored lights, Christmas ornaments, larger-than-life photos of blues giants and glittery anniversary decorations create the kind of deep, layered history that’s only enhanced by zany self-expression and fans whose ages span at least a half-century.

And Rosa’s Lounge is a family affair. Musician and owner Tony Mangiullo arrived in Chicago from Milan in 1978 to play the blues, and he opened Rosa’s in 1984.

“The story goes Tony, the owner, loved the blues so much that he came to Chicago and didn’t leave, didn’t want to leave. He’s from Italy. And he built the club and he named it after his mother,” said Cannon.

Mama Rosa was definitely the impetus for the club.

“Mama said it was not enough for Mama to see me play drums. … She said, ‘You want to be here, you have to do a business,’” Mangiullo said.

Mama clearly knows what’s best for generations of blues fans, too.

READ: 5 of Chicago’s coolest neighborhoods

B.L.U.E.S. on Halsted

A sliver of a club, B.L.U.E.S. on Halsted on the North Side of Chicago in Lincoln Park is long on atmosphere, thanks to its decidedly no-frills aesthetic and tight quarters that leave little distance between patrons and musicians.

It’s one of the first clubs Cannon played. “They put me on on a Thursday, I remember it. And I’ve been playing there for years. It’s a smaller club, more intimate,” he said.

Like many hometown musicians who’ve reached wider audiences, Cannon now plays most of his gigs on the road, but he still plays Chicago clubs about five times a year.

B.L.U.E.S., which opened in 1979, books primarily Chicago musicians, from elder statesmen like Eddie Shaw and Jimmy Johnson to younger artists who are still getting established on the club circuit.

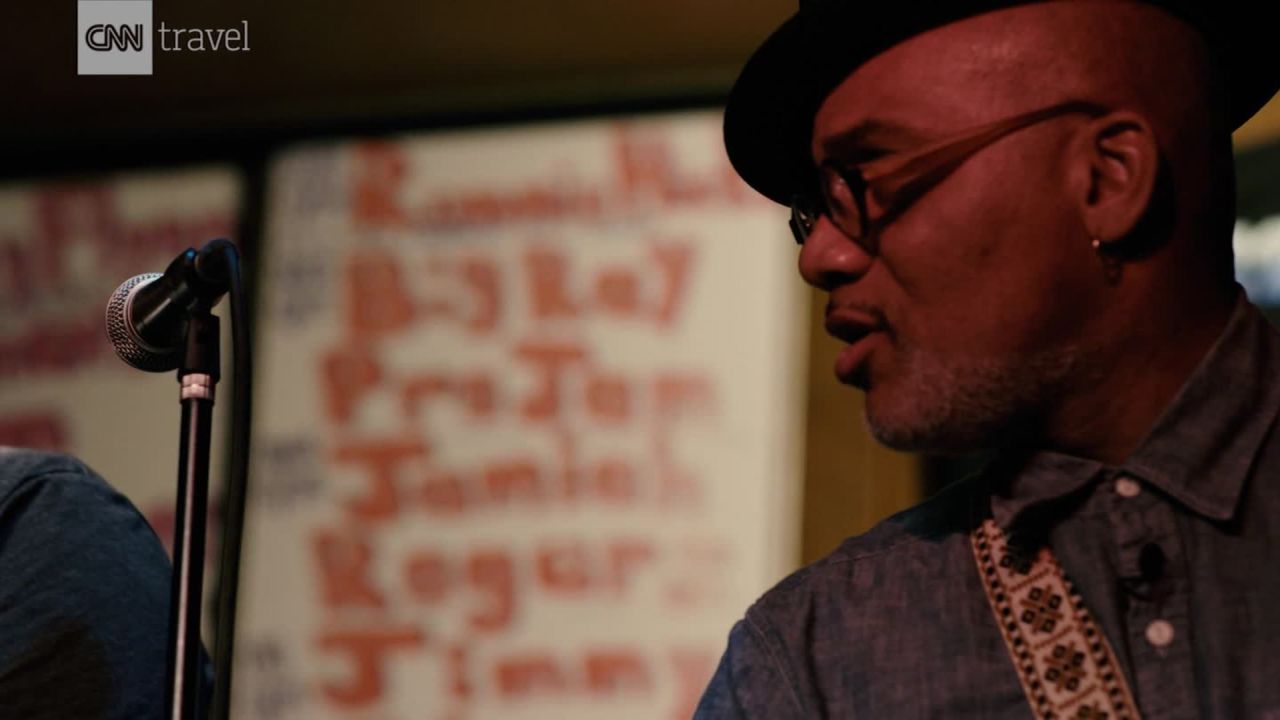

Tonight, clubgoers are perched on the cracked vinyl barstools, soaking up bluesman Jimmy Burns’ soulful tunes.

Burns also graciously ceded the stage to Cannon and Mike Wheeler, who popped over from a gig across the street at Kingston Mines to play a few songs with his friend.

The two clubs on Halsted Street have a friendly rivalry. Kingston Mines is larger, with two stages and meal service. B.L.U.E.S. keeps its offering to blues and booze.

Wheeler, 56, and Cannon, 49, are among the local artists building on traditions passed down from longtime bluesmen like Burns, 74.

And by and large, they’re doing it the Chicago way.

“I think the Chicago way means, you know, working hard and kind of using what you got to get what you want,” said Cannon.

“There’s certain things that you do in life to let people know that you’re here, and my way of letting people know that I’m here is my blues.”

If you go

Buddy Guy’s Legends: Cover charges are $10 or $20, depending on the night, and shows that start after 8 p.m. are 21 and over. Seats are first come, first served. The club serves Louisiana-style Cajun and soul food at lunch and in the evening.

700 S. Wabash, Chicago 60605, https://buddyguy.com/

Rosa’s Lounge: Cover charges range from $7 to $20. Reserved seating is available. The club doesn’t usually serve food, although catering is available for special events. Patrons can also bring food or order for delivery.

3420 W. Armitage Ave., Chicago 60647, https://rosaslounge.com/

B.L.U.E.S. on Halsted: Covers range from $5 to $10. 21 and up. On Sunday nights the cover at B.L.U.E.S. gets guests into Kingston Mines and vice versa.

2519 N. Halsted St., Chicago 60618, https://www.chicagobluesbar.com/