“Glassafe,” the above concept where seats are fitted with protective shields, has been proposed by Aviointeriors.

Plexiglass dividers between passengers, new staggered row layouts, zig-zag seating, space-age transparent bubbles around travelers’ heads – just as new divider screens popped up in shops and restaurants around the world in response to the Covid-19 pandemic, so came a wide variety of new concepts for airline seating.

In the months since, while mask mandates, hand gel and disinfectant wipes have become airline must-haves, a fundamental change to what we see when we sit down inside an aircraft cabin hasn’t followed.

At the same time, the scientific and medical understanding of how the SARS-CoV-2 coronavirus is transmitted has proceeded apace. Infection is now known to be largely via the droplet and aerosol (rather than fomite, or touch) routes, which affects the kind of protective barriers that are most effective.

Indeed, the most effective barrier is closest to the mouth of an exhaling passenger: the humble face mask. That’s why airlines are, by and large, mandating them – and banning passengers who endanger others by not wearing them.

Despite close quarters, the aircraft environment does not seem to be much higher risk than other inside spaces. Flights have continued in many parts of the world, and very few have turned out to be infection clusters themselves.

It seems that the widespread requirement to wear face masks onboard aircraft, high-efficiency particulate air, or HEPA, filtration on many aircraft and some unique aspects of the inflight environment, are likely to have contributed here.

“The reasons for the apparently low rate of in-flight transmission are not known,” noted the International Air Transport Association (IATA), an airline trade body, “but could encompass a combination of the lack of face-to-face contact, and the physical barriers provided by seat backs, along with the characteristics of cabin air flow. Further study is anticipated.”

The challenges of modifying airplane seating

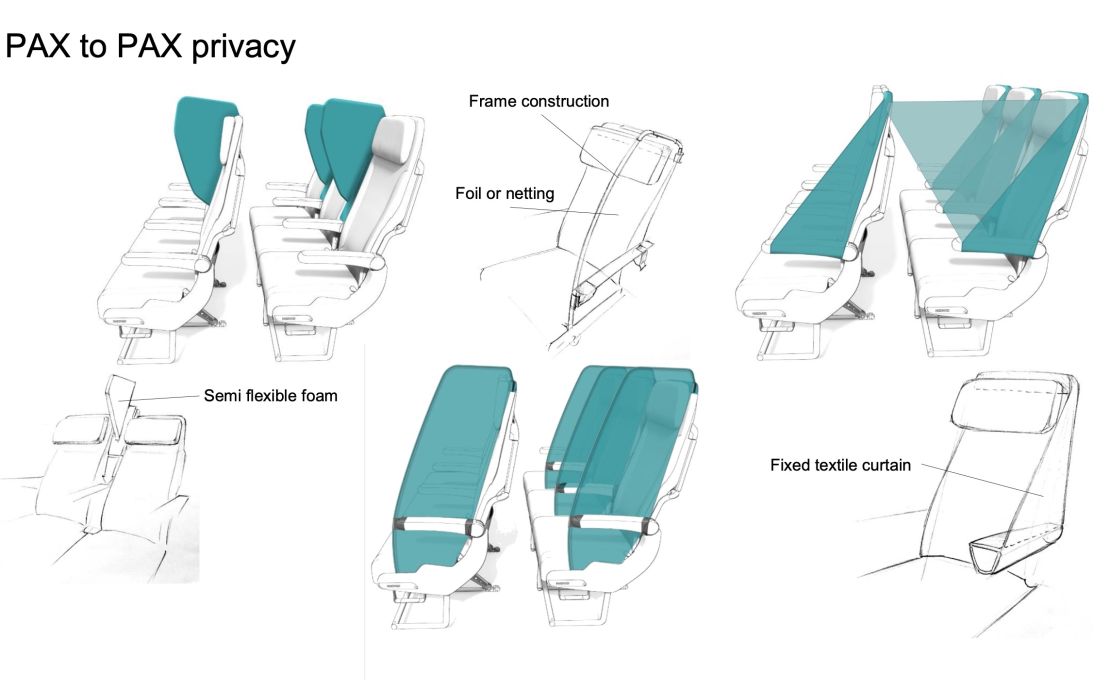

During the first half of 2020, a wide variety of cabin additions were proposed to combat the spread of Covid-19 and to reassure passengers. Transparent barriers clipping into the seatback pocket, foam inserts for the top of the seat, sculpted headrest shrouding add-ons and more.

Cabin interiors supplier companies around the world scrambled to see what they could do in the event that airlines wanted to make these big changes to their cabins.

Some companies even proposed new ways of arranging the seats, such as the Janus seat from Aviointeriors, where passengers face in alternating directions.

The proposed barriers attached in a variety of ways to the seat, and that led to very specific challenges in bringing them on board. Many of these challenges intersect, of course.

To start with, any addition to the aircraft cabin needs to be certified as safe in a variety of ways.

It must be fire-resistant and not give off fumes that might be toxic to passengers. It needs to resist incredible forces without shattering, creating sharp edges or blocking passengers’ emergency egress from their rows.

That’s true whether it’s attached to the seat or provided by the airline –?as in, for example, a foam insert to create barriers from the row behind. These barriers would, in essence, create a “sneeze guard” between rows.

Perhaps most complicatedly, anything attached to the seat in particular needs to undergo crash testing, which has become more arduous in recent years as regulators insist on ever-safer travel.

For seats and anything attached to them, this includes loading them with crash dummies and the attachments and firing them down a sled to crash with 16 times the force of gravity, without the dummy taking simulated major injuries.

“Certification has been the main challenge,” explained Mark Hiller, chief executive officer at Recaro Aircraft Seating. “When you add a feature to the seat that increases weight, the entire seat must be recertified. It’s not an easy process, but creating a long lasting, durable solution is what we are focused on.”

Recaro has proposed a number of barrier-style additions, as well as antimicrobial technology to be embedded in seat materials during the manufacturing process.

All in all, it’s much more complicated than your supermarket putting a plexiglass partition between you and the cashier.

Cost and timing are major factors

Airlines would also have to keep all of these cabin additions maintained, replacing them due either to basic wear and tear or to misuse by passengers unfamiliar with them.

Over the years, aircraft cabins have been designed and refined to be incredibly sturdy – one seatmaker openly advertises the robustness of its tray tables by having prospective customers stand on them – but the speed at which these new products have been developed may well mean that they would need to be refined after installation.

And that after-installation period is crucial. Any additions, whether temporary or permanent, need to be cleaned and serviced regularly. Adding time to the already constrained schedules of airline cleaners creates complexity and cost, while airlines would also need to keep stocks of spares across their operations.

Cost overall is certainly a factor, as airlines worldwide enter their deepest financial crisis of modern times.

“We are aware of the fact that airlines are cash strapped at the moment,” Recaro’s Mark Hiller noted, “so we must be able to prove that these solutions will provide peace-of-mind for passengers and deliver return on investment.”

So far, Recaro has no takers on its proposals for Covid-era modifications to airline seats.

Timing, too, is a point against the implementation of many of these measures?– both the expected timing of widespread vaccine availability in early to mid 2021, and the time needed to design, certify, manufacture, and install new seats or barrier additions.

In essence, there’s little benefit in completing an expensive program just a couple of months ahead of the vaccine.

Some changes are more likely than seat barriers

For now, the best ways to combat Covid-19 seem to be around minimizing contact between passengers –?and between passengers and crew.

Service standards have been changed to reduce the amount that crew circulate within the cabin, and meals have been rethought to reduce the amount of time they stay open to the air while being prepared and eaten, although food is not thought to be a transmission route.

So what is changing? Well, some of the most intense work is on baking in antimicrobial –?including antiviral?– properties into the materials used for seats and the cabin.

Tapis, a company that makes fabrics and leathers for aircraft interiors, released in August its 9-series Ultraleather with “antimicrobial, silver ion technology embedded in the surface layers that prevent leaching and efficacy loss,” which the company explained “provides a safe shield for aerosol borne micro-organisms within the aircraft to create a low risk, safe environment for passengers.”

This type of material essentially disrupts the functioning of microbes, including viruses, and tests have proven promising on the coronavirus that causes Covid-19.

Fundamentally, this is the kind of product that airlines seem to be betting on: no massive changes during the pandemic, but acknowledging that passengers aren’t going to become any less interested in onboard hygiene when the eventual Covid-19 vaccine eases the public health crisis.

John Walton is an international transportation and aviation journalist based in France, specializing in airlines, commercial aircraft and the passenger experience.