Andrew Alexander King will never forget the first time he took on Tanzania’s Mount Kilimanjaro, Africa’s tallest peak and the world’s largest freestanding mountain, in 2018.

But it wasn’t the summit that surprised the climber. It was the greeting he received when he came down, as local mountain guides gathered around him in a celebratory dance.

“It turns out they were excited because they’d never seen an African American climb,” he tells CNN. “And I was kind of just blown away by that.”

According to the American Alpine Club’s inaugural 2019 State of Climbing report only 1% of surveyed climbers identified as Black. “No one should be surprised to hear that climbing is dominated by White men,” outdoor guide and author James Edward Mills wrote in the forward of the report; of the club members surveyed, 85% were White and 72% male.

While this is a US-based poll, and the first of its kind, the lack of non-White climbers is seen and felt worldwide – from Mt. Kilimanjaro to Mt. Everest.

CNN recently spoke with King and two other Black climbers on what it will take to make the sport more diverse and inclusive across Africa and beyond.

The trailblazing mountaineer

Saray N’kusi Khumalo - CEO, Summits with a Purpose

Near-death accidents and summit failures have not slowed down mountaineer Saray N’kusi Khumalo. The Zambian-born mother of two holds a corporate job, hosts a podcast, has climbed some of the tallest mountains around the world – and still has the time to run a non-profit that focuses on education in Africa.

“My grandfather always used to say, ‘if you don’t live a life of service, that’s a life wasted,’” she tells CNN.

In 2013, she founded Summits with a Purpose in South Africa – with every climb, she raises funds to help build schools and libraries.

Khumalo’s climbs are also making a difference in the name of diversity. After she successfully completed her first big summit in 2012 – Mt. Kilimanjaro – Khumalo knew she was meant to be a mountaineer. And while she took note of the lack of diversity in her sport – “very much White-male-dominated,” she says – she never let that discourage her.

“I am an African, a very proud African when I’m on the mountain. And I’m told that the (other climbers) don’t think that I belong,” Khumalo says. “I make sure that (when) they see an African, somebody that looks like me, they remember that we are capable.”

Not long after her first-ever summit, she turned her eyes toward the world’s tallest peak: Mt. Everest, located in the Himalayas.

The first three attempts were grueling and heartbreaking for Khumalo: she experienced everything from natural disasters to losing consciousness in the “death zone,” Everest’s top stretch over 8,000 meters (26,000 feet) above sea level, where oxygen is dangerously low.

On May 16, 2019 – her fourth bid – she succeeded, becoming the first Black African woman to reach the summit. In total, only eight of the 4,000 people who’ve ever summited Everest are Black.

“I have a love/hate relationsship with Everest,” Khumalo recounts. “I don’t know if it was my greatest achievement more than just getting myself up every time I fell.”

She’s currently working on completing the Explorers Grand Slam, the quest to summit the seven highest mountains in the world and reach both the North and South Poles. To date, she has accomplished five of the summits.

Khumalo is humbled by what she’s achieved so far, but she notes, “I don’t think that I’ve broken those stereotypes yet; there’s still a lot more work to be done,” adding that representation should extend beyond the mountain tops, too.

“It’s not just about Everest; representation … is a gift that we need to leave for the next generation wherever we are,” she says, calling on her peers to step outside their comfort zone to show that Black people belong in all spaces.

The motivating explorer

Andrew Alexander King - CEO, The Between Worlds Project

Andrew Alexander King says the first mountain he ever climbed was getting out of the projects in Detroit, Michigan.

Today, the avid explorer says he’s climbed over 66 mountains. His long term goal is to climb the 14 highest mountain and volcano peaks on each continent. If he accomplishes this, he’ll be the first Black man to do so. But that’s not his motivation.

“If an individual does not see themselves at the top of Everest, at the top of Kilimanjaro … they will not pursue that because they will feel that subconsciously they do not belong,” he says.

When King began climbing more seriously in his twenties, he says, “the lack of diversity was very pronounced” and he had a heightened awareness of being the only Black person on the mountain. While climbing Aconcagua, the tallest mountain in South America, he says he was the only Black person on the expedition team – despite it being a diverse group.

“There (were) a lot of racial jokes and tension and I had to stand up for myself,” he recalls, adding that people assumed he didn’t have the aptitude for handling a tough climb.

“It did make me feel insecure, but I also use that insecurity as my rocket fuel to keep moving forward to break through that glass ceiling,” King says.

Seven years ago he founded The Between Worlds Project, which aims to help the communities where he climbs. With each expedition he goes on, he works with local non-profits on issues they are facing such as sexism, racism, climate change and inequality.

When CNN spoke with King, he was on his way back home from a two-month trip in Tanzania and Kenya where he had been volunteering in an orphanage, working with the Moving Mountains Trust and climbing Mt. Kilimanjaro and Mt. Kenya alongside locals.

“The seeds that we’re planting are going to grow – I will probably not see it in my lifetime, but we have to start planting it and nurturing it now,” King says of increasing representation. “Diversity in outdoor sports is an issue that we have to tackle together.”

The barefoot climber

Peter Naituli - Rock climber

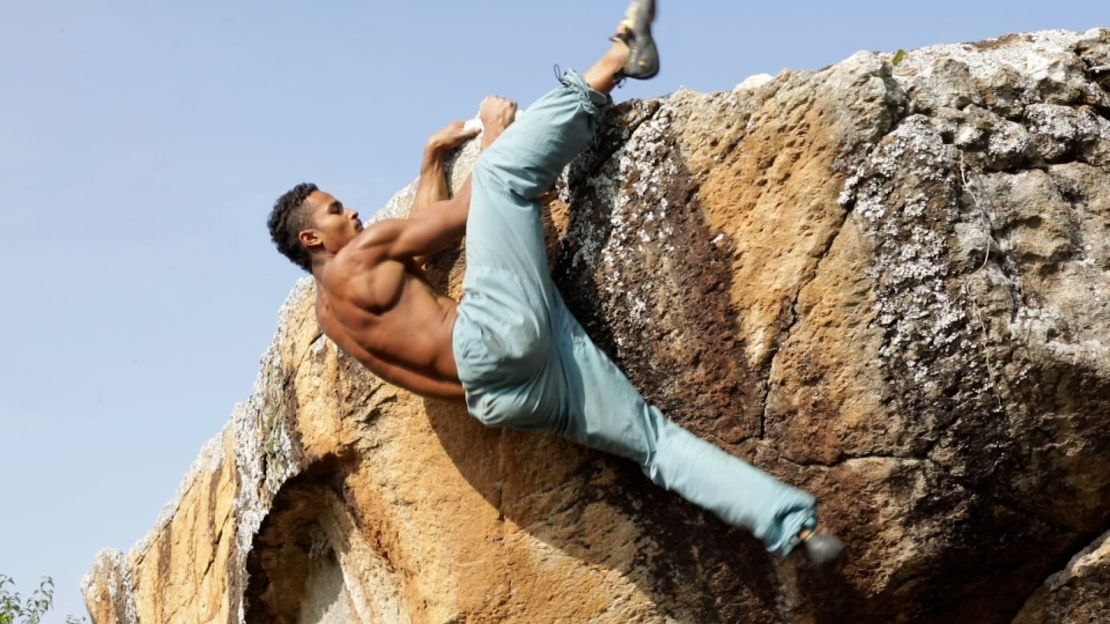

Peter Naituli is a Kenyan rock climber known for scaling mountains in his bare feet.

Without experienced climbers to guide him when he was growing up, he said he dove right into the riskier aspects of climbing – including free-soloing, which is climbing without a safety system. Through his remarkable physical feats, like climbing Mount Kenya without a rope or footwear, Naituli is proving Kenya’s place in the climbing world.

“(As a kid) one thing that was a bit boring in my climbing is I didn’t have anyone else sharing the passion with,” he tells CNN. “It was just me trying to keep the fire alive.”

In 2021, Naituli was featured in the documentary “Cold Feet,” with the intention of showcasing Kenya as a climbing mecca, in the hopes that it’ll help grow the local industry – and dispel the notion that climbing is a White sport.

“It’s not just a Western activity, it’s something here in the country, and just by watching someone else do it, (Kenyans) can have something to live up to,” he says.

Non-profits such as Climbing Life Kenya and Mountain Club of Kenya are making climbing more accessible and reducing the barriers to participate. In 2012, Climb BlueSky – the first public climbing gym in East Africa – opened its doors in Nairobi.

Still, Naituli says he’d like to see more gyms and increased access for climbing in Kenya, noting that the talent exists, but the opportunities do not.

“Having a story from a country like Kenya with the Kenyan climbers as the protagonists, that is a story which we need to tell,” Naituli says, showcasing “a different look on Kenya, a different look on the world of climbing.”