Jack Latham was on a mission to photograph farms in Vietnam — not the country’s sprawling plantations or rice terraces but its “click farms.”

Last year, the British photographer spent a month in the capital Hanoi documenting some of the shadowy enterprises that help clients artificially boost online traffic and social media engagement in the hope of manipulating algorithms and user perceptions. The resulting images, which feature in his new book “Beggar’s Honey,” provide rare insight into the workshops that hire low-paid workers to cultivate likes, comments and shares for businesses and individuals globally.

“When most people are on social media, they want nothing but attention — they’re begging for it,” Latham said in a phone interview, explaining his book’s title. “With social media, our attention is a product for advertisers and marketers.”

In the 2000s, the growing popularity of social media sites — including Facebook and Twitter, now called X — created a new market for well-curated digital profiles, with companies and brands vying to maximize visibility and influence. Though it is unclear when click farms began proliferating, tech experts warned about “virtual gang masters” operating them from low-income countries as early as 2007.

In the following decades, click farms exploded in number — particularly in Asia, where they can be found across India, Bangladesh, Indonesia, the Philippines and beyond. Regulations have often failed to keep pace: While some countries, like China, have attempted to crack down on operations (the China Advertising Association?banned the use of click farms for commercial gain in 2020), they continue to flourish around the continent, especially in places where low labor and electricity costs make it affordable to power hundreds of devices simultaneously.

‘Like Silicon Valley startups’

Latham’s project took him to five click farms in Vietnam. (The click farmers he hoped to photograph in Hong Kong “got cold feet,” he said, and pandemic-related travel restrictions dashed his plans to document the practice in mainland China). On the outskirts of Hanoi, Latham visited workshops operating from residential properties and hotels.

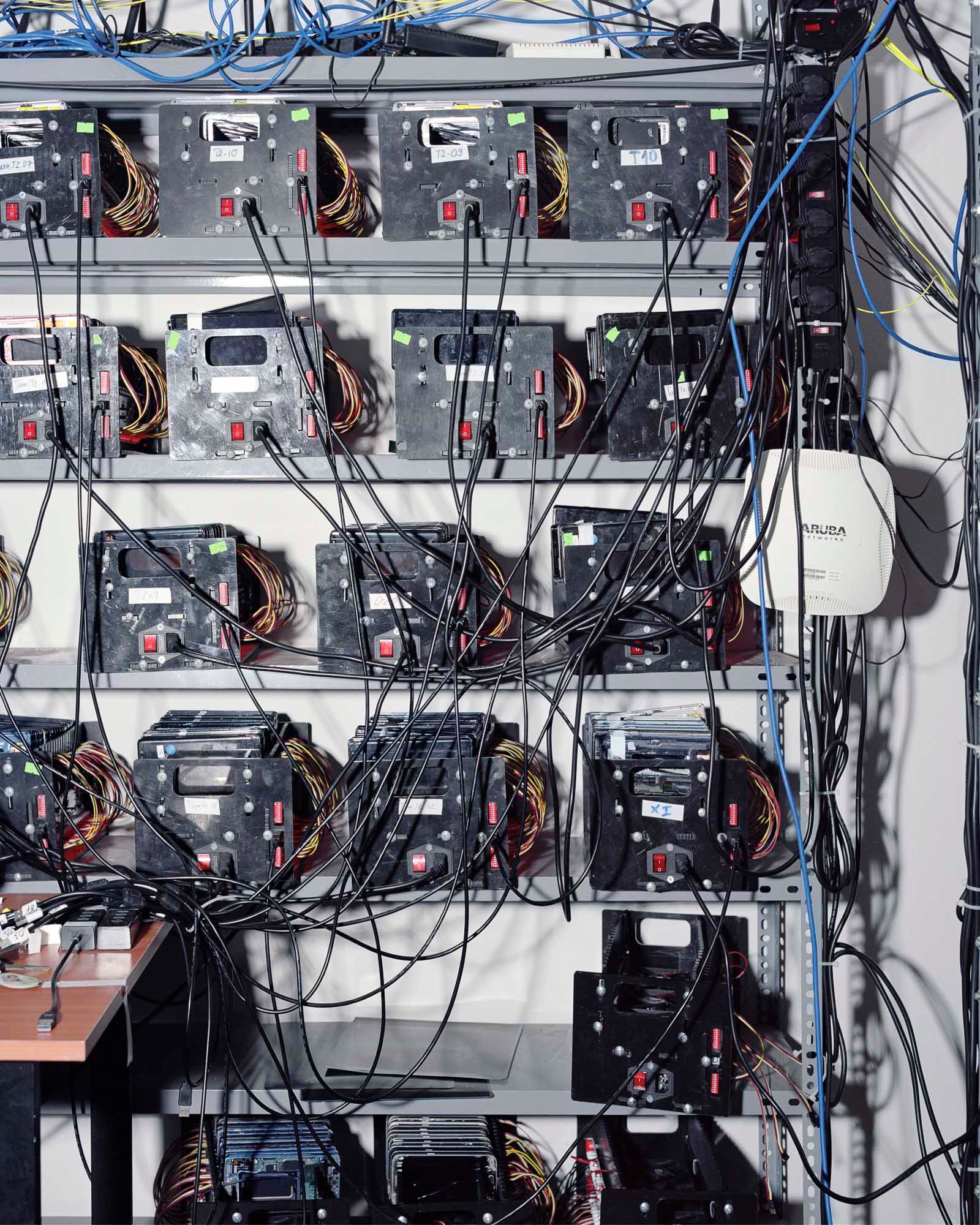

Some had a traditional setup with hundreds of manually operated phones, while others used a newer, compact method called “box farming” — a phrase used by the click farmers Latham visited — where several phones, without screens and batteries, are wired together and linked to a computer interface.

Latham said one of the click farms he visited was a family-run business, though the others appeared more like a tech companies. Most workers were in their 20s and 30s, he added.

“They all looked like Silicon Valley startups,” he said. “There was a tremendous amount of hardware … whole walls of phones.”

Some of Latham’s photos depict — albeit anonymously — workers tasked with harvesting clicks. In one image, a man is seen stationed amid a sea of gadgets in what appears to be a lonely and monotonous task.

“It only takes one person to control large amounts of phones,” Latham said. “One person can very quickly (do the work of) 10,000. It’s both solitary and crowded.”

At the farms Lathan visited, individuals were usually in charge of a particular social media platforms. For instance, one “farmer” would be responsible for mass posting and commenting on Facebook accounts, or setting up YouTube platforms where they post and watch videos on loop. The photographer added that TikTok is now the most popular platform at the click farms he visited.

The click farmers Latham spoke to mostly advertised their services online for less than one cent per click, view or interaction. And despite the fraudulent nature of their tasks, they seemed to treat it like just another job, the photographer said.

‘There was an understanding they were just providing a service,” he added. “There wasn’t a shadiness. What they’re offering is shortcuts.”

Deceptive perception

Across its 134 pages, “Beggar’s Honey” includes a collection of abstract photographs — some seductive, others contemplative — depicting videos that appeared on Latham’s TikTok feed. He included them in the book to represent the kind of content he saw being boosted by click farms.

But many of his photos focus on the hardware used to manipulate social media —webs of wires, phones and computers.

“A lot of my work is about conspiracies,” Latham said. ” Trying to ‘document the machines used to spread disinformation’ is the tagline of the project. The bigger picture is often the thing we don’t see.”

Click farms around the world are also used to amplify political messages and spread disinformation during elections. In 2016, Cambodia’s then-prime minister Hun Sen was accused of buying Facebook friends and likes, which according to the BBC he denied, while shadowy operations in North Macedonia were found to have spread pro-Donald Trump posts and articles during that year’s US presidential election.

While researching, Latham said he found that algorithms — a topic of his previous book, “Latent Bloom” — often recommended videos that he said got increasingly “extreme” with each click.

“If you only digest a diet of that, it’s a matter of time you become diabetically conspiratorial,” he said. “The spreading of disinformation is the worst thing. It happens in your pocket, not newspapers, and it’s terrifying that it’s tailored to your kind of neurosis.”

Hoping to raise awareness of the phenomenon and its dangers, Latham is planning to exhibit his own home version of a click farm — a small box with several phones attached to a computer interface — at the 2024 Images Vevey Festival in Switzerland. He bought the gadget in Vietnam for the equivalent of about $1,000 and has occasionally experimented with it on his social media accounts.

On Instagram, Latham’s photos usually attract anywhere from a few dozen to couple hundred likes. But when he deployed his personal click farm to announce his latest book, the post generated more than 6,600 likes. The photographer wants people to realize that there’s more to what they see on social media — and that metrics aren’t a measurement of authenticity.

“When people are better equipped with knowledge of how things work, they can make more informed decisions,” he said.

“Beggar’s Honey,” co-published by Here Press and Images Vevey, is available now.