After spending several days with the Haenyeo, a group of women on South Korea’s Jeju Island renowned for harvesting seafood from the ocean floor without scuba gear, photographer Peter Ash Lee said one conversation — with one of the youngest of the island’s “freedivers” — stood out from the rest.

“Her biggest concern was the fact that this tradition was ending,” Lee told CNN of Ko Ryou-jin, a third-generation Haenyeo. “She was speaking to me in Korean, and said, ‘I’m going to be the last one.’ Then she said, in English, ‘I’m the last mermaid.’”

Ko’s statement inspired the title of Lee’s new photography book, which not only spotlights the Haenyeo’s unique way of living and working — which was recognized by UNESCO as part of South Korea’s cultural heritage in 2016 — but also emphasizes how their long-standing traditions are increasingly imperiled by the climate crisis and the passage of time.

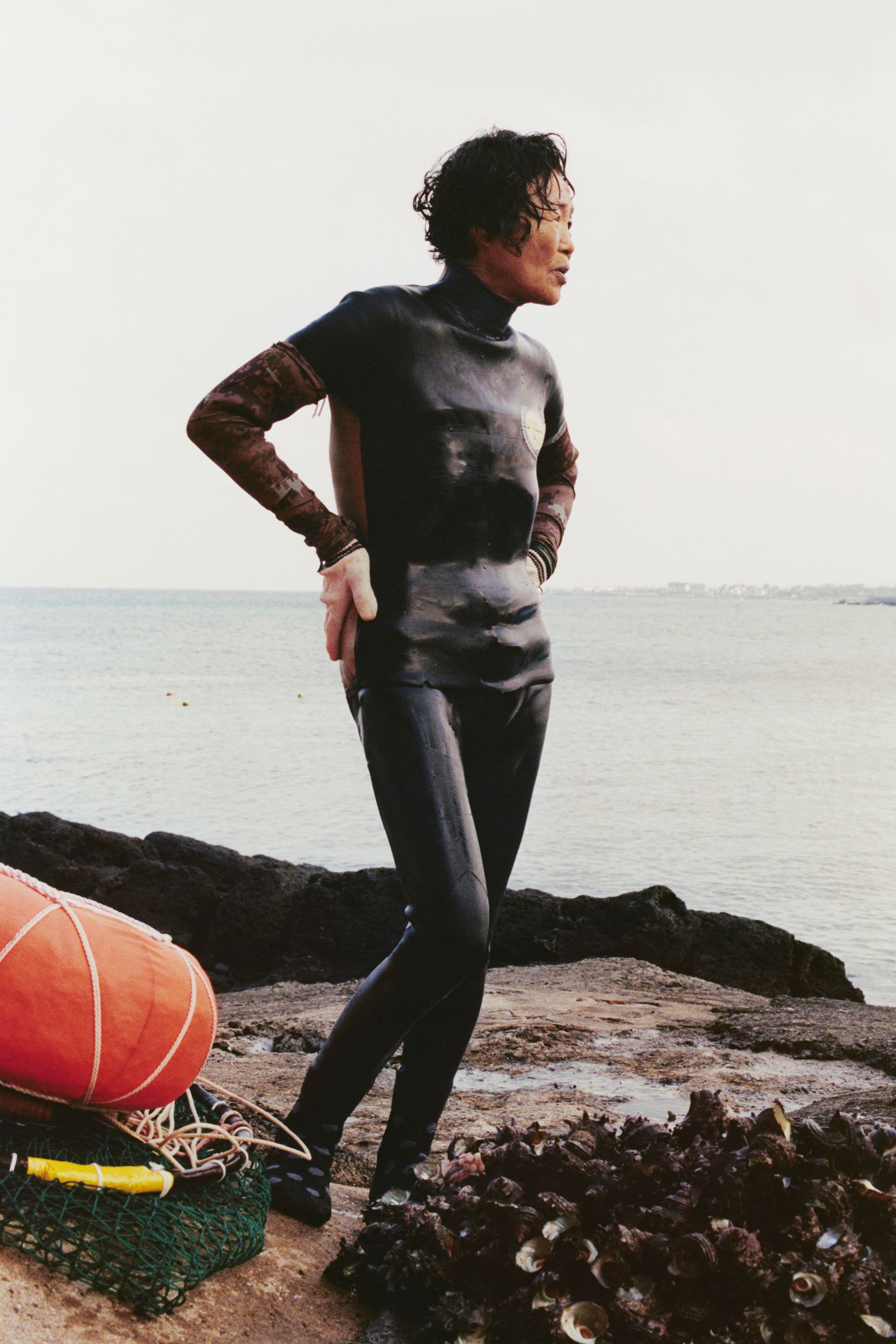

With introductory text from Ko, who Lee has kept in touch with since visiting Jeju in 2018, “The Last Mermaid” features portraits of the multi-generational group of women at work — preparing to dive with their hardy, hand-repaired equipment or emerging from the sea with their catches, hauled to the surface using nets and floats instead of modern mechanical equipment. Close-up images show the simple necessities of the job, such as the rounded lead weights the Haenyeo use to quickly sink down to the seabed as well as detailed shots of marine life, like the rows of suckers on octopus tentacles.

Lee lived in South Korea until he was seven years old, at which point his family moved to Toronto. He had always been aware of the Haenyeo, he told CNN, having visited Jeju as a child. “I think people see them almost as laborers,” he said, explaining how the Haenyeo’s unique way of life is somewhat taken for granted locally.

His desire to learn more about the community came later in life. “I was thinking a lot about diversity and representation and exploring my personal identity,” said the now New York City-based photographer, whose work has been published in Vogue, Dazed and the New York Times’ T Magazine. “As a Korean American and having spent most of my life in the US and Canada, it’s been a nice experience to go back and reconnect with my culture and heritage, and to try to share that with the world,” he said.

Bonding with the divers community over breakfasts from popular Korean bakery Paris Baguette, Lee spent long days with the Haenyeo — though did not dive himself. (“The water was very cold at the time!” he told CNN in an email.) The women, most of whom are in their 60s to 80s, would usually arrive early in the morning to prepare, including using a blood pressure machine to check that everyone was in good condition to dive, before spending their full day in the water.

The women welcomed Lee into their ranks in a way that reminded the photographer of his close relationship with his late grandmother. “Historically on Jeju Island, it was a matriarchal society, it’s the women who were diving and providing for the family, and they were the breadwinners,” Lee said. “There was this special connection… family is such a big part of the culture.”

The Haenyeo are insistent on keeping their traditions alive by using simple equipment, like neoprene wetsuits that are constantly mended and repaired, said Lee. “It was almost like history captured. They haven’t changed their way of life for the past 60 years or so.”

Yet Lee also observed challenges manifesting between old and new, with the climate crisis forcing the Haenyeo to adapt their fishing methods. The changing climate has warmed waters around Jeju by about two degrees Celsius in the last 36 years, according to a 2023 study in the journal Sustainability. Ko told Lee that it’s now no longer possible for the Haenyeo to follow the sustainable fishing practices they have cultivated over the decades due to changes in marine?ecosystems. An overpopulation of sea urchins, for example, has disrupted the divers’ regular harvesting patterns, while warmer waters have attracted poisonous and predatory sealife like snakes and octopi to the area.

Ko also told Lee that, in years past, divers could easily find their primary catch — a kind of marine mollusk called turban conch — which is often exported to Japan, where it’s considered a delicacy. Now, she says the Haenyeo have to swim out for a full hour before they start finding any. “Not only has their work become more hazardous, but it’s harder to find marine life to catch” said Lee. “Their sustainability practice has been broken. They have to work that much harder to make a living.”

Jeju’s diving traditions may date as far back as the 5th century, and the fact that the Haenyeo have quietly persevered and persisted in their traditions amid the tumult of Korea’s recent history is not lost on Lee. “(It’s) a place that has changed so much in such a short period of time, from a war-torn country that was quite poor into a developed country, and all of that is on my mind,” he said.

But those rapid economic and social developments in South Korea have meant that younger generations are often less drawn to living and laboring as the Haenyeo do, according to Ko. She has been trying to recruit more young women to join her community, but told Lee it has been a challenge. Still, there has been some success: since Lee visited the island, another younger diver has joined the Haenyeo, meaning that for now, Ko is no longer the “last mermaid.”

“It’s just amazing that there’s been this tradition that’s been around for over a thousand years,” said Lee, who is planning an exhibition of the photographs in South Korea’s capital Seoul in the spring. “I feel it’s important to preserve as much of that history as possible, because the sad thing is, I don’t know how sustainable it is.”