At Washington’s National Portrait Gallery, the centennial of the 19th Amendment, which gave men and women equal voting rights, is being marked by “Votes for Women: A Portrait of Persistence,” a comprehensive exhibition that highlights the key figures and moments in the decades-long fight for women’s voting rights.

Originally set to open on March 1 (it was delayed by the recent government shutdown, which shuttered the Smithsonian network of museums), the exhibition tells part of the complex story of how we reached where we are today, throwing into relief the struggle for women’s suffrage and the place of women’s voices within the politics of the last century.

Spaced over six rooms and a corridor, “Votes for Women” includes 124 objects – from photographic portraits to pennants and posters – that curator Kate Clarke Lemay found in museums and private collections across the country. The famed purple, white and yellow banners carried by suffragists are featured alongside artworks created by women involved in the movement, photographs of women who ran for the presidency as early as the mid-1800s, and a video installation that uses images from the National Women’s Party.

Organized thematically and chronologically, the exhibition seeks to contextualize the full history of women’s suffrage from the movement’s early roots in the early 1830s to the ratification of the 19th Amendment in 1920.

“Suffrage didn’t appear out of thin air. It came out of the abolitionist movement,” Lemay said of the often-obscured links between the suffrage movement and broader American history. “For whatever reason it hasn’t made its way to the forefront of the American mindset when we think about American history.

By placing women’s suffrage within the broader context of women’s lives, Lemay hopes to highlight the role women have played in the story of their country: “This exhibition lets us rethink and reconsider who we put at the forefront of history.”

A complicated legacy

While much of the exhibition celebrates the white women who became famous during the fight for suffrage, the exhibition also explores the racial tensions that complicates their legacy and highlights the work of women of color. Despite being at the forefront of the movement, women of color – particularly black women – are often excluded from conversations about the movement, and their struggle for voting rights after the passage of the 19th Amendment is too often left out completely. For example, Native American men and women did not gain the right to vote until 1924, when they were granted citizenship, and due to Jim Crow-era laws like poll taxes and literacy tests, black people did not fully gain the vote until 1965.

Lemay wanted to avoid those blind spots. “Black women were organizing just as much as white women,” she says, pointing out that their exclusion from national organizations and movements prompted black women to start their own organizations.

However, that obscured history posed frustrating curatorial challenges. Because of their marginalized position, women of color were less likely than their white peers to be the subject of oil paintings and large photographs – the sorts of objects viewers traditionally see as markers of importance and influence. With this in mind, Lemay was careful to include similarly sized photographs of figures within the movement, rather than risk throwing some in a more celebratory light than others.

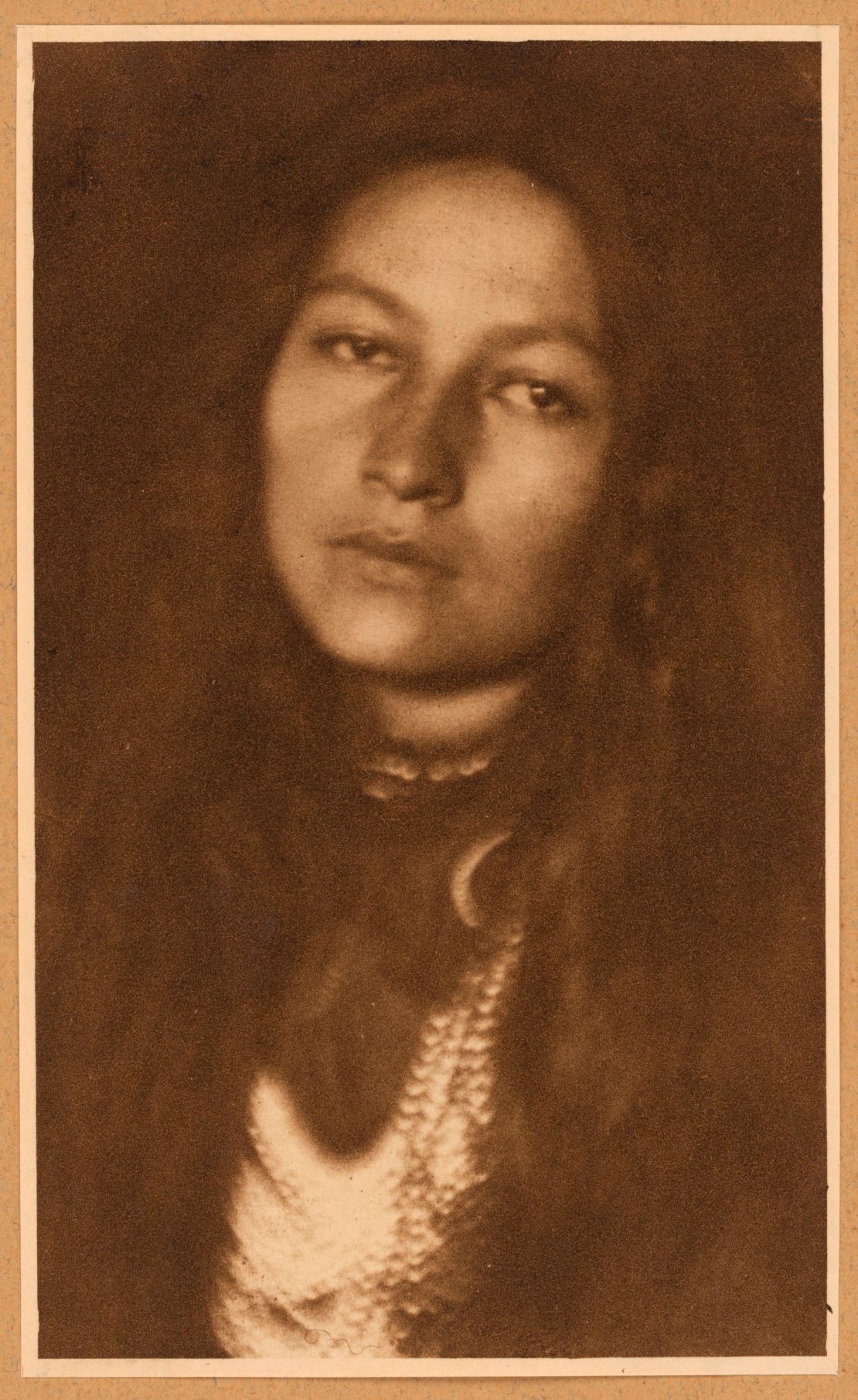

Finding photos of women of color taking part in protests was also a challenge. For example, a grainy scanned newspaper image was the only representation she was able to find of African-American journalist and civil rights leader Ida B. Wells at the historic 1913 Woman Suffrage Procession – the first parade of its kind in Washington – where she refused to march at the back with the other black participants, as she was told to by organizer Alice Paul. (Paul had wanted the parade to be segregated.)

“The ‘sisterhood’ has always been fraught,” NPG director Kim Sajet said of the discrimination that existed within the women’s suffrage movement. “This exhibition tries to take on the messy side of that history.”

“Votes for Women” ends with a look at the battles that followed the 19th amendment, including black women’s fight for the Voting Rights Act of 1965, the struggle of Indigenous communities, and the continued lack of representation for territories like Puerto Rico, where American citizens still don’t have voting representation in Congress despite being able to cast votes for the presidency. Lemay characterizes these fights as a “lonely road” too often overlooked in favor of celebrating the success of the early suffrage movement.

By framing the movement and its successes within the larger conversation around citizenship, the rights it brings and the ways in which those rights are denied to others, “Votes for Women” moves past simplistic narratives and reminds visitors that fights for citizenship and human rights are always intertwined and never over. This message is made even more resonant as activists fight the continuing fallout of the Supreme Court’s overturning parts of the Voting Rights Act in 2013, including state voter ID laws that disproportionately impact communities of color and home address restrictions on voter registrations that impact Native Americans.

As a result, the exhibition is more layered, nuanced, and challenging than many conceptions of suffrage have allowed.

“It’s not so much a celebration as a mark along the way,” Sajet says. “There were still more journeys to go, and to this day.”

“Votes for Women: A Portrait of Persistence” is on at the National Portrait Gallery in Washington until January 5, 2020.

Top image: A photo of African-American civil rights leader and investigative journalist Ida B. Wells c. 1893.