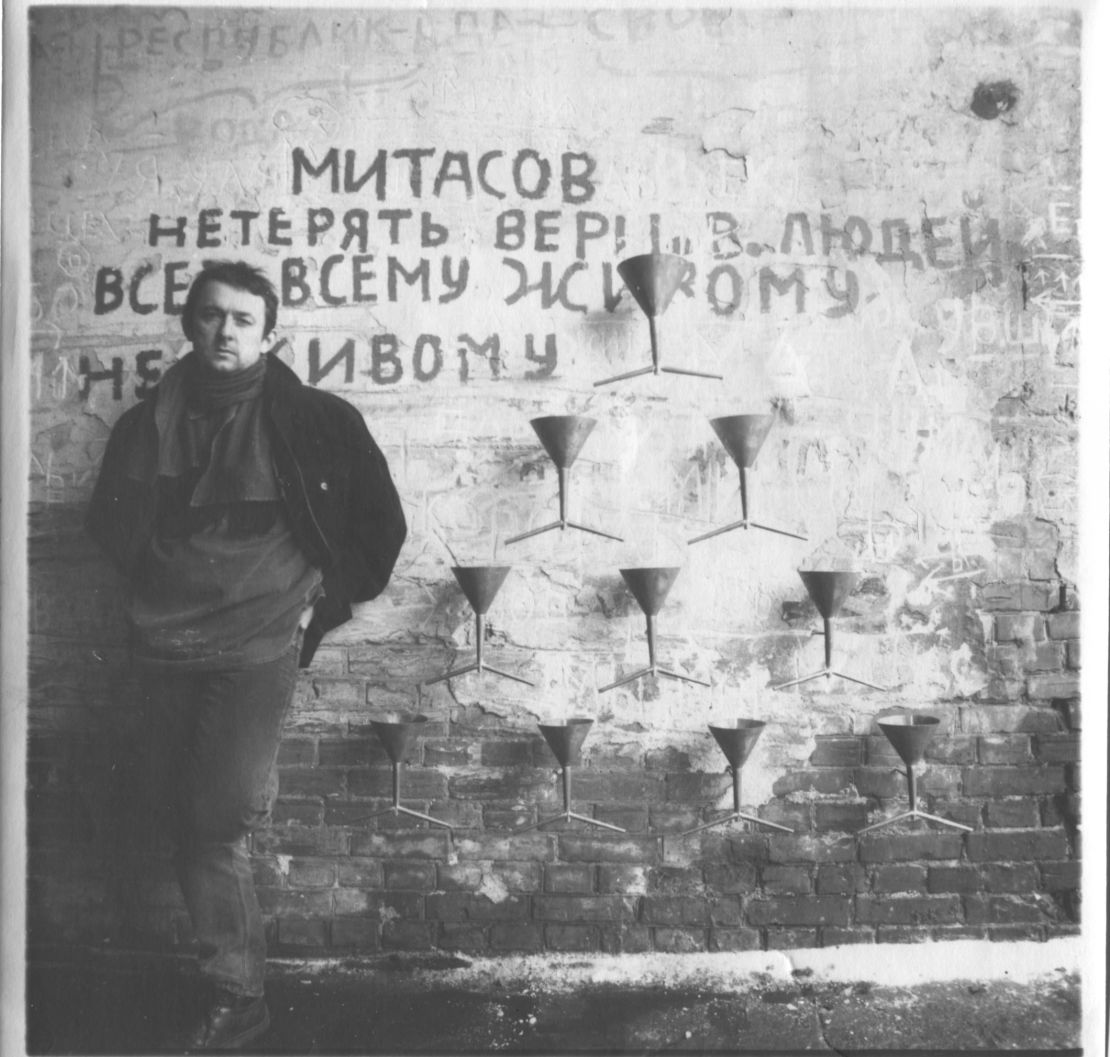

On the evening of February 24, just hours after Russia launched its full-blown attack on Ukraine, art curator Maria Lanko got into her car and left her home in Kyiv. Unsure of her exact plan, and with a potentially dangerous journey ahead, she packed only a few personal items into her trunk along with 78 bronze funnels belonging to one of the country’s most important living artists, Pavlo Makov. Her mission was to drive them out of the country to safety.

Last summer, 63-year-old Makov and his team of curators – including Lanko – had won a bid to represent Ukraine at the Venice Biennale, a prestigious international event known as the “Olympics” of the art world. The funnels were crucial parts of their proposed entry, a water fountain sculpture called the “Fountain of Exhaustion.”

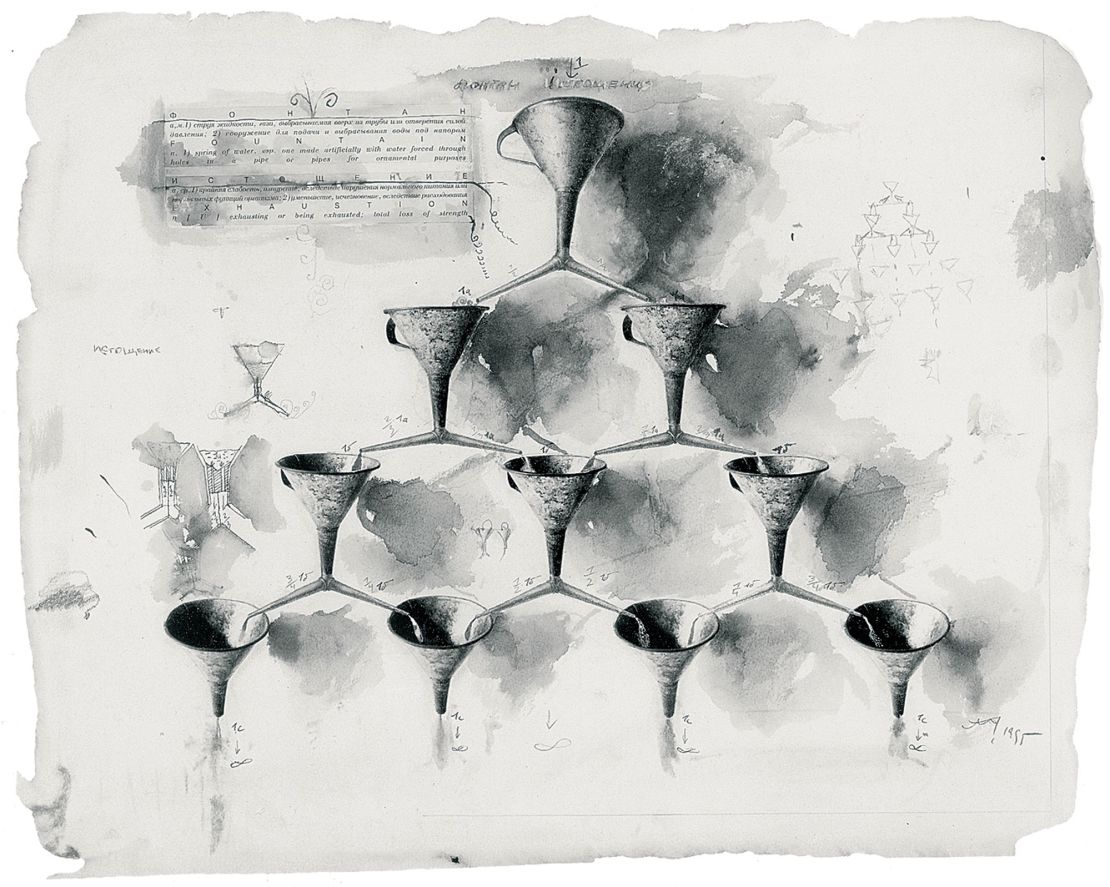

The artwork was first conceived in Kharkiv, a city in northeast Ukraine, where Makov has lived and worked for over three decades. It was the mid-’90s, and the post-Soviet country was still undergoing a period of transition after its people voted for independence in a 1991 referendum. The fountain was intended to be a metaphor for the social and political exhaustion Makov witnessed as his country grappled with the civic and economic challenges of rebuilding an independent state. Constant water shortages in the city also inspired him to view the project from an ecological perspective as he ruminated on the idea that resources are finite.

Over the years, “Fountain of Exhaustion” took many forms, from sketches and prints to technical drawings and physical installations. The version planned for Venice was to be the first fully functioning fountain, with the 78 funnels mounted in such a way that the initial stream of water divides again and again as it makes its way down the triangular arrangement, its flow weakening until it reaches the bottom.

The week before Russia invaded Ukraine, Makov and his team ran a test on the newly constructed fountain to ensure the water flowed properly. Thanks to design and technical assistance from Forma (ФОРМА), a Kyiv-based architectural practice, the installation worked. The team was elated.

Soon after that, everything changed. While the threat of conflict had been building, giving the team time to consider contingency plans, the sudden attack on Ukraine made the possibility of unveiling the installation in Venice, then less than two months away, seem impossible.

The journey from Ukraine to Italy

Personal safety was the team’s priority in the conflict’s early days, as they scrambled together escape and shelter plans with family and friends. One of Lanko’s co-curators, Lizaveta German, was heavily pregnant and living in an apartment in Kyiv when the war began. Just days away from her due date when the first missiles were launched, German wanted to stay in the city to be close to her maternity ward. But as the situation worsened, she and her husband made the difficult decision to move west to Ukraine’s cultural capital Lviv, a city that was under less immediate threat. There, she was joined by the project’s third co-curator, Borys Filonenko.

Lanko, meanwhile, was still driving. After six days on the road, the 78 funnels crammed into three boxes, she crossed the border into Romania. Later, exhausted from the near-constant travel, she made a rest stop in Budapest, Hungary, before eventually ending up in Austria’s capital, Vienna.

There she waited for Makov, who was working on his own evacuation plan. He had been in Kharkiv when the war began, gathering his family in his apartment for the first two days. But the city was under such heavy bombardment that they were forced into a bomb shelter for nearly a week, and as the situation worsened, the artist decided to flee, driving out of the city with his 92-year-old mother, his wife and two other women.

German gave birth to a baby boy on March 16 in Lviv. Speaking to CNN in a hotel in the city ten days later, she reflected on art’s role in times of extreme crisis. “I do believe that art has this symbolic potential to celebrate people’s lives and to show that we are still here – to show that Ukraine isn’t just a war victim,” she said.

By that point, Lanko had made it to Italy. She found a production company in Milan that agreed to re-create the parts of the installation she had left behind in Ukraine.

Suddenly, it seemed that – against all odds – they would make it to Venice. There was also a growing sense among the team members that they should act as ambassadors for their country. As their fellow Ukrainians fought Russia on the front lines, served in hospitals and took volunteer roles, Makov and his team were beginning to mount a different kind of defense against the invasion.

“Ukrainian art has been overshadowed for a very long time by Russia,” said German, holding her baby close to her chest. “The cultural field has to be a battlefield as well, and we have to fight.”

Weeks later, Lanko, Filonenko, Makov and German (with her infant) were eventually reunited in Venice to complete final preparations together.

Attention ‘paid by blood’

Speaking on Monday, two days before the project’s press unveiling, Makov said he did not think of himself as an artist but rather a citizen of Ukraine whose duty it is to represent his country.

“I realized that it would be important for Ukraine to be represented (at the Biennale).”

With an influx of interest from media and the art world, the sculpture, once a broad reflection on how the world has exhausted itself, had taken on a new meaning. It had, by default, become a piece of “war art” – and being in the spotlight has proved difficult for the team. “It’s a little bit paid by blood,” said Lanko.

“We embrace all the attention because we understand that we’re the ‘speakers’ at the moment – the ambassadors of our country and of our culture,” she continued, explaining that she hopes the conversation surrounding the pavilion can address Ukrainian art more generally.

As it turns out, Makov was not the only Ukrainian artist whose work was on show during the Venice Biennale’s opening week. A solitary work by the late Maria Prymachenko hangs subtly near the entrance of the main pavilion, in the festival’s Giardini area – a quiet tribute to one of the country’s most esteemed 20th century artists, whose name made headlines last month when a museum containing more than a dozen of her works was attacked by Russian forces. It’s feared that not all of the art was salvaged from the blaze.

A message from the President

Further afield, in a building about 30 minutes walk from the main Biennale site, there also stands a exhibition of work made by Ukrainian artists over the last few weeks. It’s a powerful reminder of the many creative people who have been impacted by the war, and another example of the determination and resilience of Ukrainian artists.

One such artist, Lesia Khomenko, is showing a series of large-scale portraits called “Max in the army,” which she named after one of her subjects: her husband, Max, who joined the military resistance. Another work, “Difficulties of Profanation II” by Nikkita Kadan, sees large pieces of shrapnel and rubble – collected from Donbas in 2015 during the last Russian attack on Ukraine, and then from Kyiv in 2022 – hanging from a frame.

Speaking via video at the exhibition’s opening event, President Volodymyr Zelensky of Ukraine said, “Art can tell the world things that cannot be shared otherwise,” as he urged the audience to support his country with art, words and their “influence.”

The exhibition’s curator, Bj?rn Geldhof, orchestrated the show in just four weeks. During a walk-through of the space, he said: “Creating in war time is not easy. But that’s one of the things we wanted to do is show the incredible resilience that Ukrainian contemporary artists have.”

This strength of character was on full display at the Ukraine pavilion on its opening day. A press conference to mark the unveiling began with a moment of silence for the people in Ukraine. And while media and visitors continued to voice suggestions that the team behind the installation are heroes, Makov and his curators batted away platitudes by reminding people that the real heroes are those on the battlefield, in the hospitals and in areas under siege.

The team was also measured in its assessment of art’s ability to end conflict. “I’m always saying that art is more diagnosis than a medicine,” said Makov. “I’m not quite sure it can save the world, you know? But it can help to save the world.”

Speaking weeks before, Lanko had expressed similar views: “Art won’t stop the war right now, but it might stop the next one,” she said.

For German, the “Fountain of Exhaustion” is not a symbol of optimism, but she believes the fact they got it to Venice at all will “give hope” and show that Ukraine is capable of forging ahead in the darkest of times.

“Even although the war is still around, we are capable of building our future.”