Editor’s Note: “Another Round” won best international feature film at the 93rd Academy Awards on April 25. This story, published ahead of the awards, features an interview with director and screenplay writer Thomas Vinterberg about the production and the personal tragedy that shaped the film.

In a just world, the booze-soaked function rooms of the annual awards circuit would have spent the last few months raising a glass to Thomas Vinterberg. The Oscar-nominated director of “Another Round” has collected several garlands already, including a BAFTA, for his film about a quartet of Danish teachers who embark on a drinking experiment to shake off the ennui of middle age.

If ever a movie was suited to the bacchanalian rituals of Oscars season, his might be it. Alas, the pandemic.

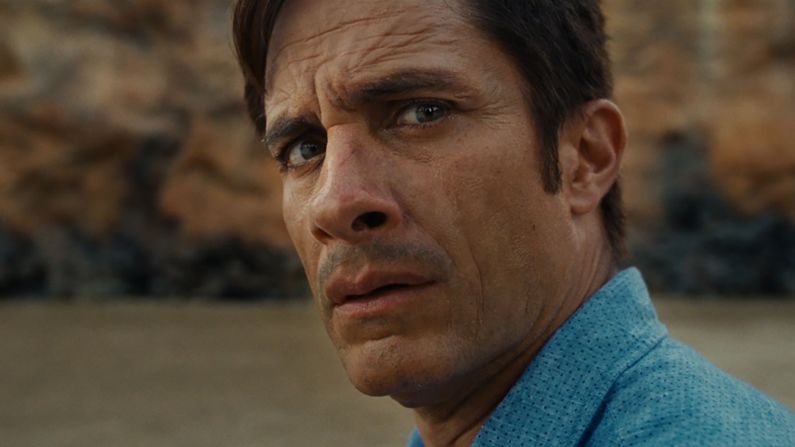

Starring Mads Mikkelsen alongside other Vinterberg regulars Thomas Bo Larsen, Magnus Millang and Lars Ranthe, the film’s characters Martin, Tommy, Nikolaj and Peter test out a psuedo-scientific hypothesis that humans are born with less alcohol in their blood than required for optimum performance.

Seeking to rectify that (and then some) they drink through the day, swigging from sports bottles, sniffing spirits and downing heady Sazerac cocktails of cognac and absinthe, recording their findings as they go. But as they start seeing the benefits, issues arise in their personal lives.

At first blush, its good-natured look at learning to find happiness again appears a long way from Vinterberg’s roots in Dogme 95, the radical filmmaking movement he co-founded in the 1990s, which disavowed cinematic conventions, denounced the industry’s artifice and even disallowed directors a credit. And yet elements arguably linger in its DNA.

Whatever reading of the film you make, its success at the box office and recognition at the Oscars – the heart of the establishment, where it is nominated for best international film and Vinterberg for best director – represents a remarkable career arc for the Dane.

It’s also remarkable that the film exists at all. In 2019, Vinterberg experienced a terrible personal tragedy when his daughter Ida died in a car accident. She had been set to perform in the movie, which was filmed on location at her school. The project went on hiatus; when the director returned, he would go on to make the most uplifting film of his career.

Ahead of the Academy Awards on April 25, CNN spoke with Vinterberg about what makes a good drunk performance, how “Another Round” connects with his other work, and finding a higher purpose on a film set.

The following interview has been edited for length and clarity.

CNN: Congratulations on your BAFTA win. How did you celebrate?

Thomas Vinterberg: With a whiskey sour and some champagne. It was a great night.

I wondered if you might’ve gone for a Sazerac…

Well, we’ve had some Sazeracs down the line.

Speaking of which, I’d like to ask about the drunk boot camp you did for preparation, where your actors drank and measured their blood alcohol content (BAC) like they do in the film.

It was a delightful experience but also a lot of hard work, to be honest. Acting is interesting, because when you have to convey something, it’s very much about hiding what you want to convey. It’s the same when you play drunk. You hide that you’re drunk; you measure your movements and you button up and you sit straight and try to walk straight. But what we really had to rehearse was technical stuff like articulation, or lack of articulation. And then what happens above 1.0 (% BAC), when you become physically challenged by the drinking. That’s where it starts looking silly on screen, and that’s what’s so difficult, so we rehearsed a lot.

I read that at one point this film was going to be an outright celebration of alcohol. When did you decide to alter that approach?

Pretty early in the process. We found that making a pure sort of provocation was a bit too arrogant, too young, too limited, and we felt it was more grand and truthful to tell the whole story about alcohol. This is something I normally steer away from, but I felt the moral obligation. I know people who have lost their lives to alcohol, and so has (writer) Tobias Lindholm.

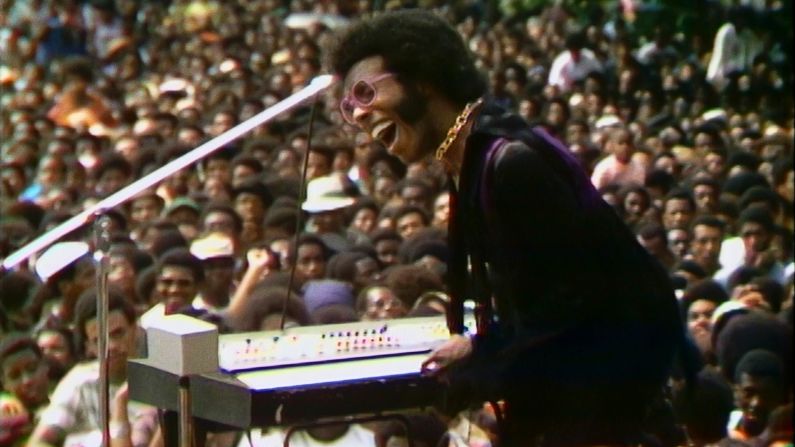

This film is distinctly Danish – you can’t separate it from its context. You’ve spoken about this idea, that through specificity you can connect with a wider audience. Do you think the industry is in a good place right now for independent filmmakers, and filmmakers working outside of English, to be able to tell their stories without the need to compromise or stray into generalization?

I’ve been saying this, that the level of specificity is what makes it universal. Other movies that I’ve seen this year – in “Nomadland” and “Minari” and others – live from this specificity, and that’s what makes them rich. And so does “Another Round;” it is so much grown out of Danish soil and Danish drinking culture.

I had to write about something I know. So it did not only become about Denmark, it became about my daughter’s school, and the neighborhood which I’m in, and teachers that I’ve met in my life. And I wrote it for my friends – specifically for these four actors. Familiarity and specificity were incredibly important to make it believable.

You’ve described this as probably the most honest film you’ve made. Could you explain that?

When I did my graduate film back in the day, “Last Round” (1993), it was so naive and so open and unguarded. And then I grew older, got a career, became famous, and you become increasingly corrupted and intentional. And it’s a constant battle against those things. In this case, I felt it was so important from the beginning that it was raw and honest, or else it would lose every element of value; it would just be silly provocation. Then I lost my daughter, and we were all paralyzed with grief. And I guess it disarmed us completely and left us very open. I don’t know how to explain it, otherwise. It’s as if the film took control of itself and we just followed.

You stepped away from the production after your daughter’s death, then came back. What made you return?

It gave a me purpose in life and kept me away from the freefall. And I felt there was a higher purpose in making a movie for her. Before her death it was an ambition to make a life-affirming film; that became a necessity. I wanted to celebrate the life that we lose so easily.

Just having a place to go in the morning was a huge help. They (the actors) carried me through, I think. They granted their entire life to this, and so did the film crew, and hopefully it’s on the screen and the hopefully it’s there to honor her memory.

I wanted to rewind to 1998 and your film “The Celebration” (the first Dogme movie). Both the main character in that film and in this one down a glass of wine, and both narratives pivot on that moment. It might’ve been a coincidence, but is “Another Round” in dialogue with any of your previous films?

It’s not intentional, but it’s obviously a signature of a kind. I think it has a lot in common with my whole career, this film. It primarily has to do with the whole Dogme thing, because it’s about a group of people embarking on a crazy project without knowing whether this is going to end good or bad, and which creates a lot of love and solidarity between them, because it’s connected to an element of risk.

The glass of wine in “The Celebration” serves exactly the same purpose. It’s like it’s an agreement you make with yourself and your surroundings: now things are going to spin out of control. And in both films, it’s about control. In (“Another Round”), they’re purposely trying to lose control, because control has taken over their lives.

On the subject of Dogme, this film ends on a cathartic moment, where we have this pitch perfect piece of additional music – something not allowed by the Dogme manifesto. Looking back, do you see the benefits of breaking your own rules?

So you’re saying this is very far from a Dogme movie?

Well, it is and it isn’t …

If I put on the hat of the (Dogme) Brotherhood, this would be considered a very decadent movie because it’s full of my own tastes. It’s full of me, and that was what we tried to abstain from back in the Dogme days – which was obviously impossible, because the more we undressed, the more personalized it became. So we were sort of caught up with our own rules.

This is not a Dogme movie, yet some of the same virtues have been taken back. It’s a handheld movie. It’s a movie that has rough edges; it’s bumpy. It’s kind of an uncontrollable beast. We don’t use score to smooth it out. We let it live through its unevenness, and that has given us the same element of honesty, I guess.

I was speaking to the production team of “Nomadland,” and they mentioned Dogme when describing their approach. How do you feel about this idea you came up with pretty quickly–

(In) half an hour.

How do you feel all these years later, about Dogme finding its way into different filmmakers’ lives in different parts of the world, in totally different contexts?

I’m super proud. It was a complete cleansing of moviemaking and it was a nice mirror to have had. If I say, ‘now we’re putting up a lamp’ (on set), we think about why we do it. When we add score, it is because we want to tell you something, it’s not just because that’s how you do it. We took away the conventions of filmmaking, and I understand why other filmmakers need that mirror sometimes.

Lastly, what are you plans for Oscars night?

My plan is to dress up and try to remain calm. And on the night I’ll have a Sazerac, for sure.