London-based designer Priya Ahluwalia uses her eponymous fashion label to explore her Indian and Nigerian heritage and tackle fashion’s colossal waste problem.

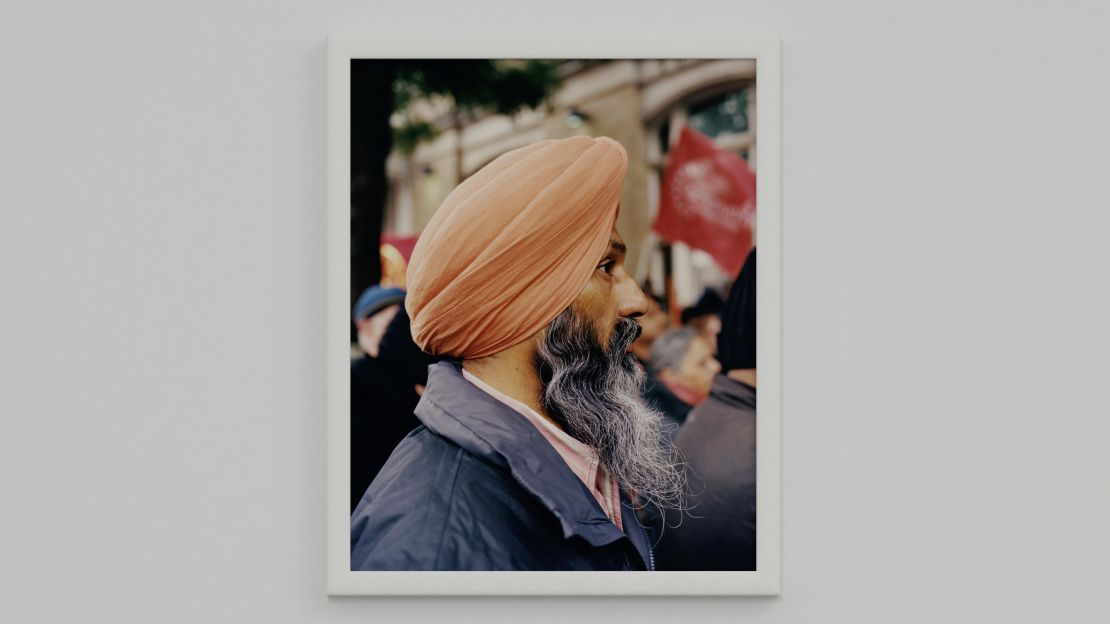

At London Fashion Week (LFW) in June, which went digital due to the coronavirus pandemic, Ahluwalia presented a virtual exhibition that displayed photos from her latest book, “Jalebi,” rather than a new collection of clothes. The project shines a light on West London’s Punjabi community in Southall, and was a statement about the rich cultural contribution of immigrants to the UK.

Ahluwalia’s first foray into photography was her 2018 book “Sweet Lassi,” released alongside her graduate collection for her Menswear MA at the University of Westminster. The book chronicled formative trips she took to Lagos, Nigeria, and Panipat, India, where she saw the scale of the second-hand clothing industry. The eye-opening experience influenced her sustainably minded practices, including her use of deadstock – old, unsellable fabric – in her designs.

For the VR exhibition of “Jalebi,” Ahluwalia brought together photos of her family with shots of Southall residents. Here, Ahluwalia discusses the exhibition and fashion’s role in social issues.

Why did you choose Southall as the focus of your latest book and recent exhibition?

I always visited Southall as a kid as it was the best place to get things for Indian cooking or Indian clothing. It used to be a big family day out and I enjoyed it so much. I started to realize as I was getting older that a lot of people (in London) had never heard of Southall, and I thought this was crazy seeing as we lived in the same city.

Brexit had just happened as well as the Windrush scandal and there was an increasingly hostile environment for ethnic minorities. I wanted to create a piece of work that celebrated the beauty in diversity.

What were some of the things that resonated for you while documenting Southall, and what do you want readers to take away from “Jalebi?”

I kept thinking about how as a community, (Southall is) so unique because of two specific cultures coming together in a specific geographical location. For example, a Punjabi community moving to Texas would create a different environment. The visual language would be completely different, the shop signs or the specific mixes of East and West fashion.

I also just kept thinking about how much I love Punjabi food, to be honest. I would be lying if I said the smells didn’t distract me a lot!

How did your journey documented in ‘Sweet Lassi’ inspire your use of deadstock in your designs?

In 2018 I visited Lagos to see my family. I noticed a trader wearing a London Marathon 2012 shirt and another wearing a Korean T-shirt. I was intrigued and dug deeper, moving forward on a hunch that the presence of these textiles heralded a larger story.

I learned all about the second-hand clothing industry which led me to visit Panipat, a city north of Delhi, to photograph the global garment recycling capital of the world. I was fascinated and also worried about how much we throw away. Visiting Panipat was life-changing and I decided to start my brand with sustainable principles.

Do you feel like it’s important for fashion brands to have a voice outside of their clothing designs?

Not necessarily, because I do believe every brand should do what feels right to them. I feel more like a multidisciplinary creative and so I think it reflects naturally into the brand. I also like the idea of storytelling and creating a world for anyone who is interested.

Many young designers seem to be directly commenting on racism, lack of representation in the industry and the climate crisis. Do bigger brands need to do more?

I think the correlation between young designers talking about these issues is that more young designers are of BAME (Black, Asian, Minority Ethnic) backgrounds than ever before. This means that for the first time, designers from ethnic minorities are able to share their stories and work through their own voice.

All big companies, not just fashion brands or magazines but businesses across all industries, need to consider whether their companies are feeding into a system that allows racism to continue and grow unchecked.

Talking specifically about fashion brands, I do think bigger companies need to do more. In the high street or affordable bracket of brands, I have been shocked by the amount of them that shared a Black square on #BlackOutTuesday but have also stopped paying their accounts to factories in Africa and Asia due to the pandemic, leaving the workers destitute.

To me this is a clear example of systemic racism, because the workers are seen as far away and unrelatable due to heritage and skin color – it is not seen as important to treat them fairly. These companies really need to implement these changes through every part of their supply chain. This to me is more important than virtue signaling at fashion week.

How do you think the pandemic will influence the fashion industry going forward?

I think it has shown that there are other ways to present ideas than very exclusive runway shows, like the VR exhibition used to display “Jalebi.”

I also love that this (presentation) has enabled people to see the project on a global scale and it has really increased accessibility. The idea of accessibility has been really important to me and I would love to continue to explore this in the future.