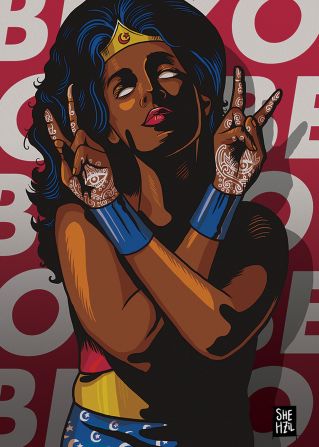

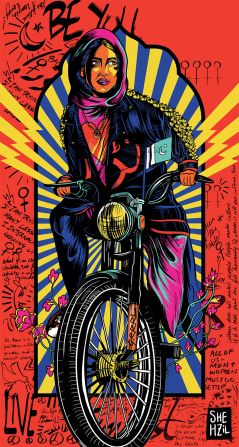

Shehzil Malik began producing feminist graphics as a form of “catharsis” – a counterweight to the gender inequality she sees in Pakistan. Her vibrant, subversive images, which include hijabi bikers, tattooed women and a brown-skinned Wonder Woman, were a defiant kind of therapy.

“Pakistan is a difficult place to be a girl,” she said from her home in Lahore.

Pakistani designer ignites debate with powerful feminist graphics

Coming from a wealthy family, Malik is profoundly aware that her experiences don’t reflect those of all women in the country. But many of the struggles she addresses cross boundaries of social class: oppressive beauty and sartorial strictures; pressure to marry; restricted independence and freedom of movement; sexual harassment and violence that Human Rights Watch describes as “routine.”

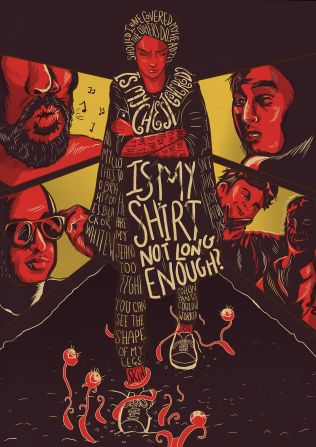

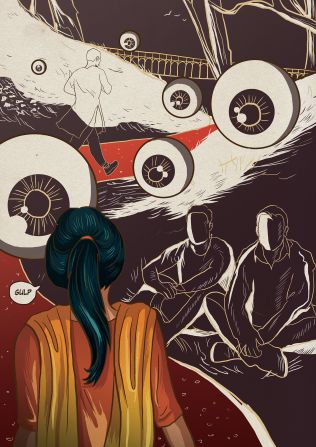

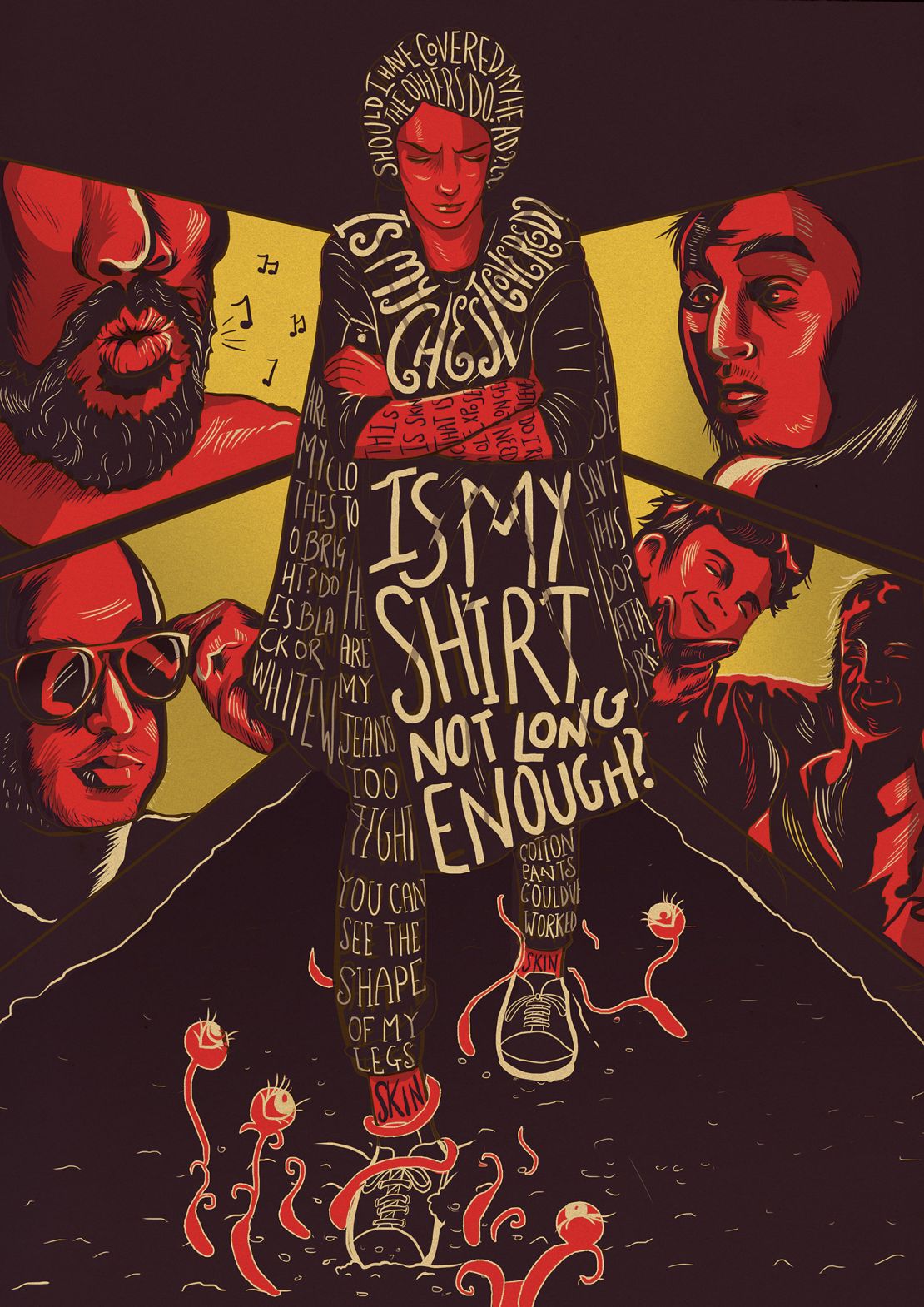

Her first series, which was about “the anxiety of stepping outside,” was unflinching in its critique of the status quo. One of the comic-style illustrations, which drips in satire, depicts the preparation required for women to become “socially acceptable” – necklines, hemlines, shawls, hair, makeup, embellishments. Another graphic shows a collection of floating eyeballs looming over a lone woman.

Walking the streets is “not what Pakistani girls do,” said Malik, whose own predilection for public space inspired the series.

“Everyday without fail,” she has written of her daily walks, “I’d be followed, heckled, sung to and stared at. I’ve been groped more times than I can remember.”

Sparking conversations

By creating aspirational graphics for women and girls, Malik hopes to undercut popular, patriarchal consciousness. She was prepared for a misogynist backlash, but she didn’t anticipate just how popular the images would become.

The series and its accompanying hashtag, #womeninpublicspaces, went viral, sparking long-awaited conversations about women’s attire, street harassment and sexual assault. Malik’s social media following shot into the thousands, while messages of support and solidarity flooded in.

“It all just developed a life of its own online,” she said. “It was one of those cosmic moments – everyone started talking about women in public spaces.”

Wittingly or not, Malik has decided that she’s “sort of a propaganda artist.” In one of her most shared works, Malik depicts a woman removing skin-lightening cream as part of her “Brown is Beautiful” series.

“When I was a child,” read the accompanying words, “my fair-skinned grandmother would scrub me with pumice stone till my skin was raw to try to wash away my brownness.”

In the years that followed, Malik said she felt compelled to try everything – including various toxic concoctions – to meet a beauty standard that regards lighter skin as more desirable. The cycle only stopped when she traveled abroad.

“Surrounded by women of all colors and shades,” she said, “I finally felt beautiful.”

Malik believes that her images have proven popular because they narrate a collective trauma.

“I feel like all of us are struggling with identity 99 percent of the time, because it’s just not acceptable to be yourself,” she said. “When something goes against the grain, it really hits a nerve.

“Women who have been sitting on difficult feelings for a long time don’t have to express things for themselves – someone has said it for them.”

Wearable feminism

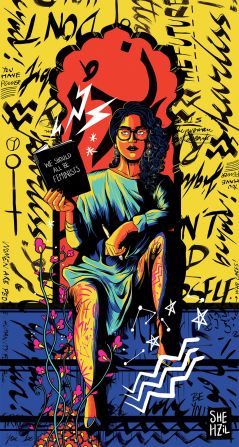

Late last year, Malik launched one of the first clothing lines in Pakistan to be explicitly marketed as “feminist.”

Produced in collaboration with Pakistani fashion brand Generation, the collection of tops, tunics, jumpsuits and jackets are printed with Malik’s illustrations, in addition to quotes from Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s book “We Should All Be Feminists,” and empowering statements in Urdu and English.

“(The collection is) not for the male gaze, but for women to recognize their own inherent strength,” she said. “This (clothing) line was an experiment to see if I could make artwork that would be seen on a national level and (that could) normalize the idea of feminism and strong women.”

As well as making the collection “wearable” and acceptable in Pakistani society, Malik also wanted “to create something of beauty that sparks conversations.”

“A person becomes a walking, talking artwork,” Malik said. “You don’t have to go to a gallery; the work isn’t behind closed doors. I want everyone – friends, family, cooks – to ask questions, so people have conversations they wouldn’t otherwise have.”

The collection sold out soon after its release, and Malik, who often visits stores carrying her merchandise – in order to watch shoppers’ reactions – claims she has seen men taking interest and even wearing some of her items. “The way people have embraced it has been amazing to watch,” she said.

There are, of course, millions of Pakistani women without internet access or significant disposable income who may never encounter Malik’s work. Simultaneously pleased with the potential of her art and aware of its limitations, she hopes her future creations can reach the women in less economically privileged positions. They are, she believes, the country’s hidden heroes.

“If you go to the villages, those women are way cooler,” she said. “They’re farmers, they’re driving trucks, they’re mothers, they’re getting sh*t done. They’re not the ones given the mantle of ‘feminist,’ but I feel like they’re doing so much more than me.”