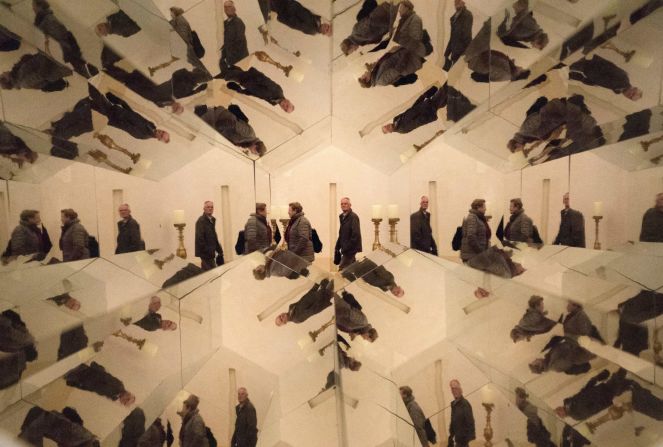

Olafur Eliasson likes to play with fire – but also ice, light, temperature and pressure. His larger-than-life art installations remix the elements and shock the senses to provoke a reaction, physical as much as emotional, in the viewer.

For his seminal 2003 installation “The Weather Project,” he put the sun and the sky in a hall of London’s Tate Modern gallery, complete with 200 lamps, mist machines and its own weather forecast service. People reacted to it in unprecedented ways: They started lying down to watch themselves in the mirrored ceiling, organized picnics, came in fancy dress – someone even brought a canoe.

Such a reaction is what he was hoping for: “When we are in a museum or a gallery, we are in a space in which exploration feels possible. It’s a situation where we’ve been cultivated to take more risks than we would in a street or a private space,” said the Danish-Icelandic artist who’s in London for the release of Phaidon’s “Olafur Eliasson: Experience,” a guide to three decades of his art.

“You behave differently when you’re moving through an art installation, which allows you to explore movement and the consequences on your body. It drives your brain into your body. It connects them at least.”

This is what great cultural institutions are there for, Eliasson said. “They are an opportunity for people to almost do a little fact-checking: Do I actually feel myself or have I become numb? That’s why it’s sometimes hard work to go to a museum – it’s not like going to a shopping mall, where you’re just being pleased, you’re kind of sleepwalking. In a great cultural institution, you’re being provoked, and you have to have an opinion about something.”

“The Weather Project” didn’t immediately stimulate an environmental discussion – in 2003 climate action was hardly the order of the day – but it undoubtedly represents Eliasson’s first step into that arena. Since then, he’s often earned the moniker of “environmental artist.”

In 2015, as world leaders were about to sign the Paris climate agreement, which the United States withdrew from in 2017, Eliasson put 12 massive blocks of glacial ice in a Parisian street for people to touch. Harvested as free-floating icebergs from a fjord in Greenland, they were meant as a stark reminder of the critical state of the Arctic ice caps.

Olafur Eliasson's brave new worlds

“I’m interested in what type of knowledge or experience makes people take action,” he said. “So when I did the ice blocks, I was looking at what the physical presence of the ice does to your body when you can literally put your hand on it. And it struck me that people would say, ‘Oh! This is cold!’ – even though theoretically we know very well that ice is cold. But it just shows us that the physical relationship with the world and the knowledge about the world are disconnected.”

That’s why the threat of climate change, he said, does not give us enough sense of risk to result in actual action. An emotional experience, on the other hand, can be a stronger driver of behavioral change than theoretical data.

“Climate awareness has never been so high,” he said. “There is basically no place in the world where a 12-year-old does not know what global warming is. We are reaching the point where everybody on the whole planet is being introduced to the notion of the greenhouse effect. So the headlines are not so good, but the trends underneath is. We don’t see convergence, we don’t see execution, we don’t see commitment yet. But I do think we are seeing change.”

That the cultural sector has been a massive source of that change is not surprising to Eliasson: “There is more money in the cultural sector than in the car industry,” he said. “We just forget it because it’s decentralized, it’s messy, it’s chaotic. We think it’s a small thing but it’s not, it’s like a huge network of things that are actually reflecting on critical questions.”

Can art save the world then? Eliasson said he is optimistic about the power, and the responsibility, of culture to inspire action despite “a lot of old institutions still governed by old white guys with white hair who have been sitting there way too long.”

“How can we organize our narrative so that we can have a more intimate relationship with the greater civic society? Maybe the cultural sector can offer solutions to some of the things that politicians are struggling with, such as not reacting on the climate – because they’re not,” he said.

In 2012, Eliasson founded Little Sun, a company that makes solar-powered products designed to replace kerosene lamps and power small electrical items in areas without a grid, such as sub-Saharan Africa. But it would be limiting to paint his interests and creations as confined to the environment.

For two months he opened a pop-up restaurant in Reykjavik, Iceland, with his sister and chef Victoria Elíasdóttir, inspired by the communal kitchen of his Berlin studio, which employs about 100 people. His passion for food is such that an upcoming personal retrospective he’s putting together at London’s Tate, opening in late 2019, might well include a full-size restaurant, too.

About the still work-in-progress exhibition, he’s only willing to say, “I’m happy to report it takes on a slightly larger ambition than my shows otherwise.” Brace yourselves.

Eliasson has also founded an architectural practice, which has recently completed its first building, a castle-like office block in Denmark. His previous flirts with architecture have resulted in the acclaimed Harpa Concert Hall in Reykjavik and the 2007 Serpentine Pavilion in London, among other efforts.

“I’ve worked with architects and in the process I’ve really come to appreciate the great artistic craft of architecture. So with my studio manager, who’s an architect I’ve worked with for 15 years, I’ve started a practice, simply acknowledging that there are things that architects just do better.”

The boundary between architecture and art is an increasingly blurry one, but Eliasson said he has no trouble picking his side. “For me, the question I’m answering is art, but the language I’m using to answer that question is architecture,” he said.

“But I’m an artist, and I’m very happy to be an artist.”

“Olafur Eliasson: Experience,” published by Phaidon, is out now. Top image: “Ice Watch,” Paris, 2015.