Editor’s Note: In October 2015, Balmain creative director Olivier Rousteing joined CNN Style as guest editor. He commissioned a series of features on the theme of #diversity, exploring issues around fashion, politics, gender, family, race and culture.

Story highlights

Contemporary fashion is deeply rooted in French history

The French designers of the 1960s and early 1970s challenged traditional elegance with radical ready-to-wear

As war and the sexual revolution influenced designers in the past, globalization has shaped the fashion landscape of today

I didn’t go to fashion school. I’ve been against formal education ever since I discovered Santa Claus isn’t real, so everything I learned about fashion growing up, came from reading magazines and looking at photos.

I remember watching this beautiful movie, “Falbalas” from French director Jacques Becker, showing the life of a couturier in the 1940’s and the production of a fashion show, when I was 12 years old. The show had movement, it had life, and it had theater and it really captured my imagination. I’ve been fascinated by designers who evoke drama ever since.

For that reason, I’m very proud to be from France, which has given the world so many pioneering designers. While I don’t believe there’s anything innate about the French and style, it’s impossible to deny that contemporary fashion’s roots are in this country. From the beginning, France – and Paris in particular – has been the capital and heart of fashion, with a long list of innovators who changed the way we looked at clothes, the body and even ourselves.

And as the world becomes smaller and the industry more global, that history and influence are more important – and wider felt – than ever before. Experimentation, variety and quality can come from anywhere today, but the ones who laid the groundwork for this did so in France.

French fashion innovators

Like many designers, I admired France’s most celebrated, original and audacious couturiers.

Christian Dior’s ground-breaking “New Look” changed the way women dressed around the world. His February 1947 collection’s signature rebelled against wartime uniforms, austerity and fabric restrictions — the waist was cinched, calves were shown and busts were celebrated.

Madame Grès had a wonderful haute couture house, Grès, and she worked in her own universe. Originally a sculptor, her silk jersey pleated dresses looked as though they had been pulled out of ancient Greece.

But it was the designers of the 1960’s and early 1970’s who truly pushed boundaries, challenging the traditional elegance of haute couture with radical prêt-à-porter (ready-to-wear) collections.

After decades of classic sophistication, this new wave of designers brought something fresh— in tune with the sensibility of the time in which we were living. They knew about the sexual revolution, about going into space, about modernism and architecture, and used that in their work. No one had seen anything like it before.

I started working with Pierre Cardin when I was 18. He was one of the industry’s top innovators. I’d always admired Cardin because he seemed like such a showman. He was so free, doing these geometric, sometimes abstract designs that were like architecture, which he had studied before he went into fashion. He also designed everything from furniture to industrial design to car interiors.

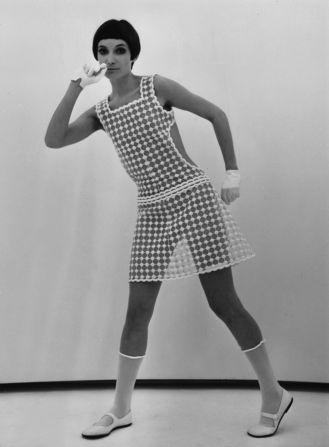

André Courrèges worked at Balenciaga for 10 years before opening his own house. He was a trained engineer before becoming a designer, and from early on I was always under the impression that he was starting a revolution. I realize now it was because he was actually dressing the real woman of the 1960’s — a modern woman who drove, rather than sipping cocktails at home. His clothes may have looked futuristic, but they were perfect for that moment.

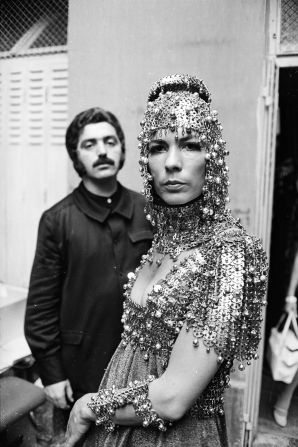

I also loved Paco Rabanne, who invented the incredible metallic dress. It was everywhere, worn by all the major yé-yé singers – the rock and roll girls of France — and Brigitte Bardot and Barbarella also wore Paco Rabanne. That was really important to me because I was always influenced and inspired by what actresses and singers were wearing. The jet set were just unfashionable and tacky – I looked to women with personality.

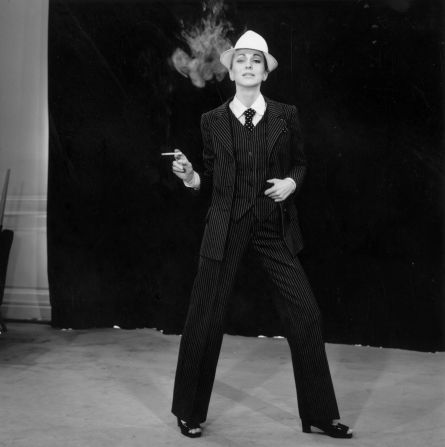

Then there was Yves Saint Laurent, who was always different from the others. He was scandalous and really reflected change – the sexual revolution, the rise of liberal beliefs in France – in a glamorous way. He approached innovation fabulously, showing a woman in a suit, but without sacrificing her femininity.

Learning from those who paved the way

I’ve always tried to be honest and push boundaries in the same way as those before. I never wanted to dress the classic, elegant type and I realized early on in my career that what the critics say is chic isn’t always so.

My career really began in the mid-1970’s. By then, Paris had somehow become more conservative. Fashion wasn’t like what you see in the movies: after the hippie period of the 1960’s, people began to dress with less of a sense of adventure, as if they were rejecting fashion, and dressing very plain. I wanted something else, and so what I did at the beginning shocked a lot of people.

After Pierre Cardin, I went on to Jean Patou, an old couture house that no longer exists. It was stereotypical of the more traditional French fashion code. When I arrived to work in my biker boots, they said “But why? Where is your motorbike?”

And so I decided that when I created my own collection, I would push the limit of what’s beautiful and what’s not.

When I started designing for myself in 1976, many found my work too sexual, and for a long time the French fashion press ignored me. “He plays, he makes games, it’s not real clothes,” they said.

Of course they were real clothes, just simply put together and played with. Who says you can’t wear a biker jacket with a tutu, or that men can’t be sexy and androgynous?

The younger generation of women responded. They wanted that mix, and I was doing something that pleased them.

So much changed since then. Now, Saint Laurent, Courrèges and Cardin are heroes in French fashion history, and the French press hasn’t criticized me nearly as much over the last 20 years — making me question whether I’m doing something wrong!

The latest generation of French designers is doing wonderful things – Olivier Rousteing makes beautiful clothes for beautiful people at Balmain; Nicolas Ghesquière is fantastic; I love the attitude of Hedi Slimane at Saint Laurent – but dynamic designers from other countries are keeping rebellion and difference alive in this country too.

Like war and occupation shaped the ’40s, and the sexual revolution changed the world in the ‘60s, globalization has changed the landscape of today.

Now more than ever, Paris Fashion Week is where the world’s most talented and provocative strive to build their brands and share their point of view because they know what Paris represents: creativity, audacity and, still, prestige.

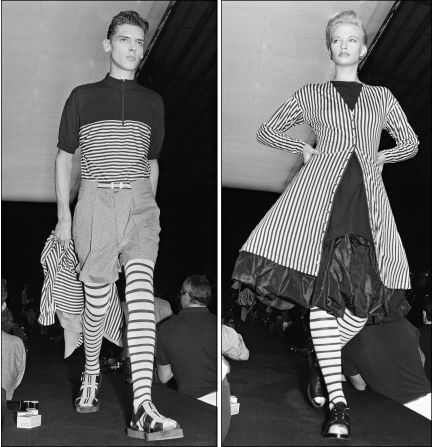

Here I think of the creative Japanese designer Rei Kawakubo of Comme des Gar?ons, my former assistant Martin Margiela from Belgium, Vivienne Westwood from England, and Rick Owens from America – all of whom have shown on schedule here.

Like the French visionaries I admired when I was growing up, these international designers have opened my eyes to incredible – and sometimes shocking – new concepts and ideas. They have their own world and their own identity, and do things you cannot expect from anyone else.

How very French of them.

As told to CNN’s Allyssia Alleyne