At 91 years old, Jasper Johns is one of the most important living artists today, with auction sales worth tens of millions of dollars and a seven-decade career credited with changing the course of 20th-century art.

But the American artist has always been reluctant to engage with interpretations or even showings of his work, leaving curators to present it as they like – and viewers to reach their own conclusions.

His latest retrospective, “Jasper Johns: Mind/Mirror,” is a massive dual-city show featuring hundreds of paintings, sculptures, mixed-media works and prints, with one half on display at the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York and the other at the Philadelphia Museum of Art (PMA).

“I’m not very interested in exhibitions of my own work,” Johns told CNN over email. “As I’ve said before, the work is too familiar.”

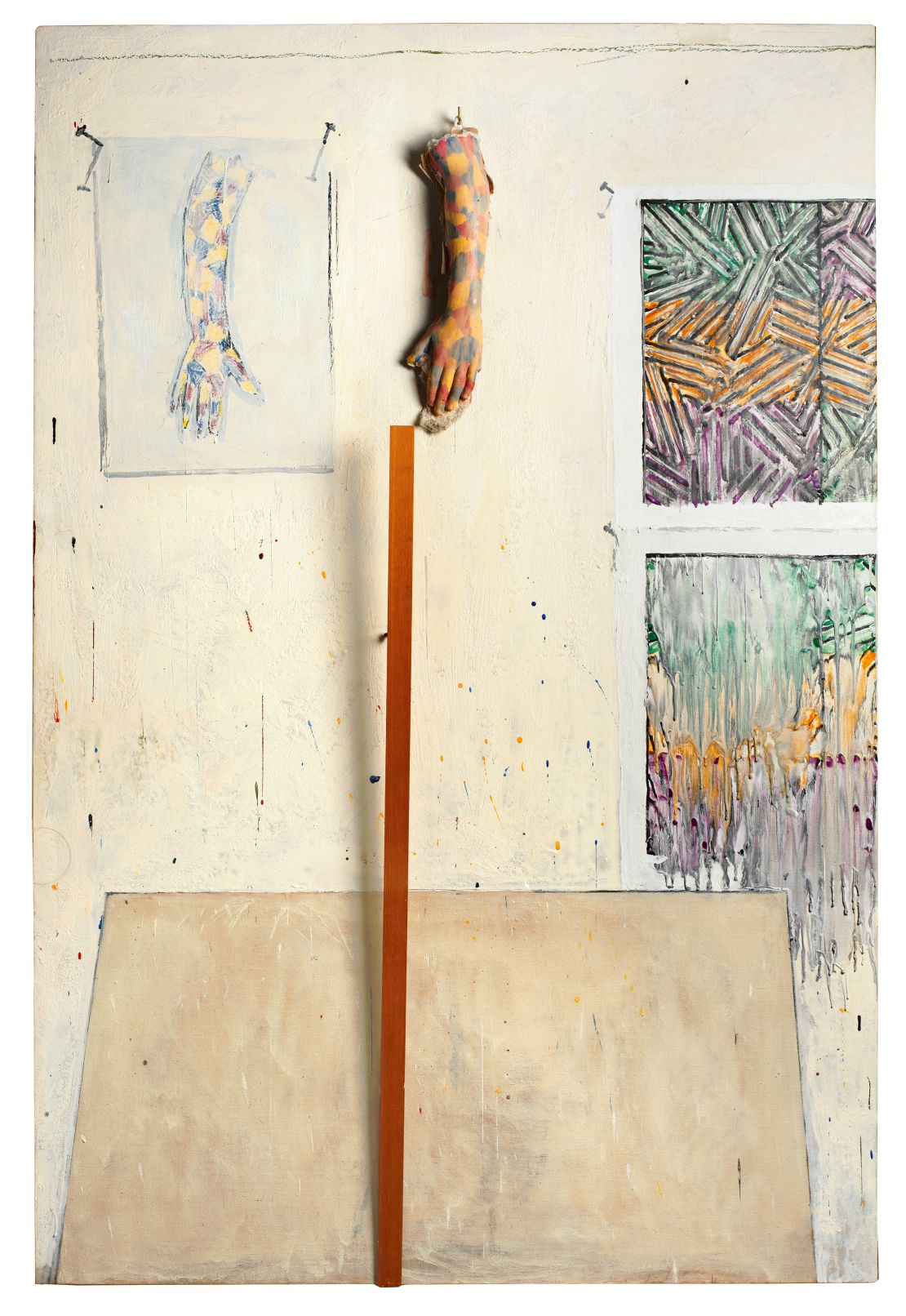

Johns has spent his entire career shifting viewers’ perspectives on the illusory quality of artmaking, contending with the picture plane and the nuance of reproduction.

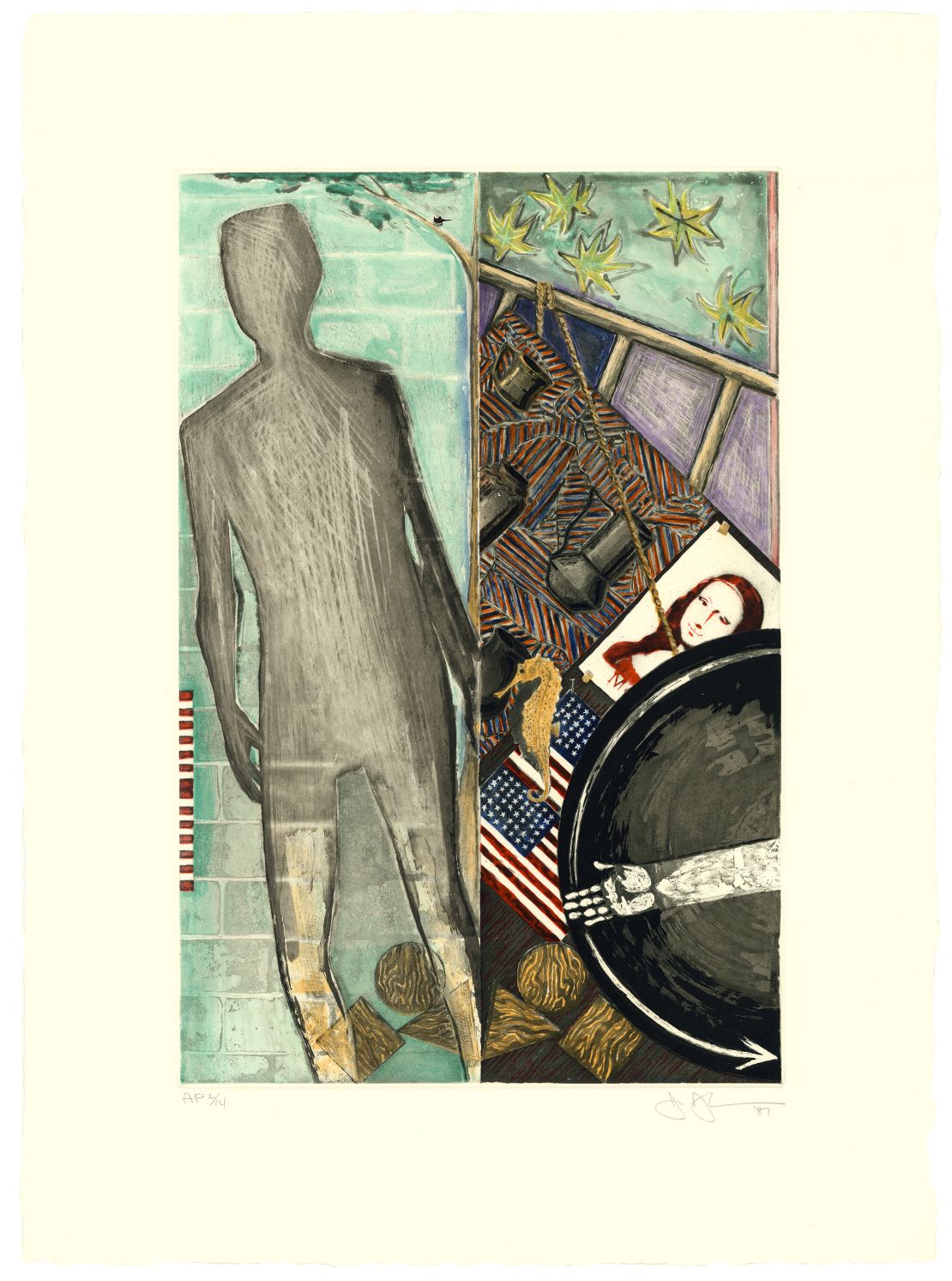

Glance at his works and you see the familiar motifs he developed early in his career – an American flag, a target, a series of numbers – but spend time with them and you start noticing the textures and imperfections. What actually makes a flag? It is both a physical object and a concept, a duality we perceive but perhaps never consciously consider.

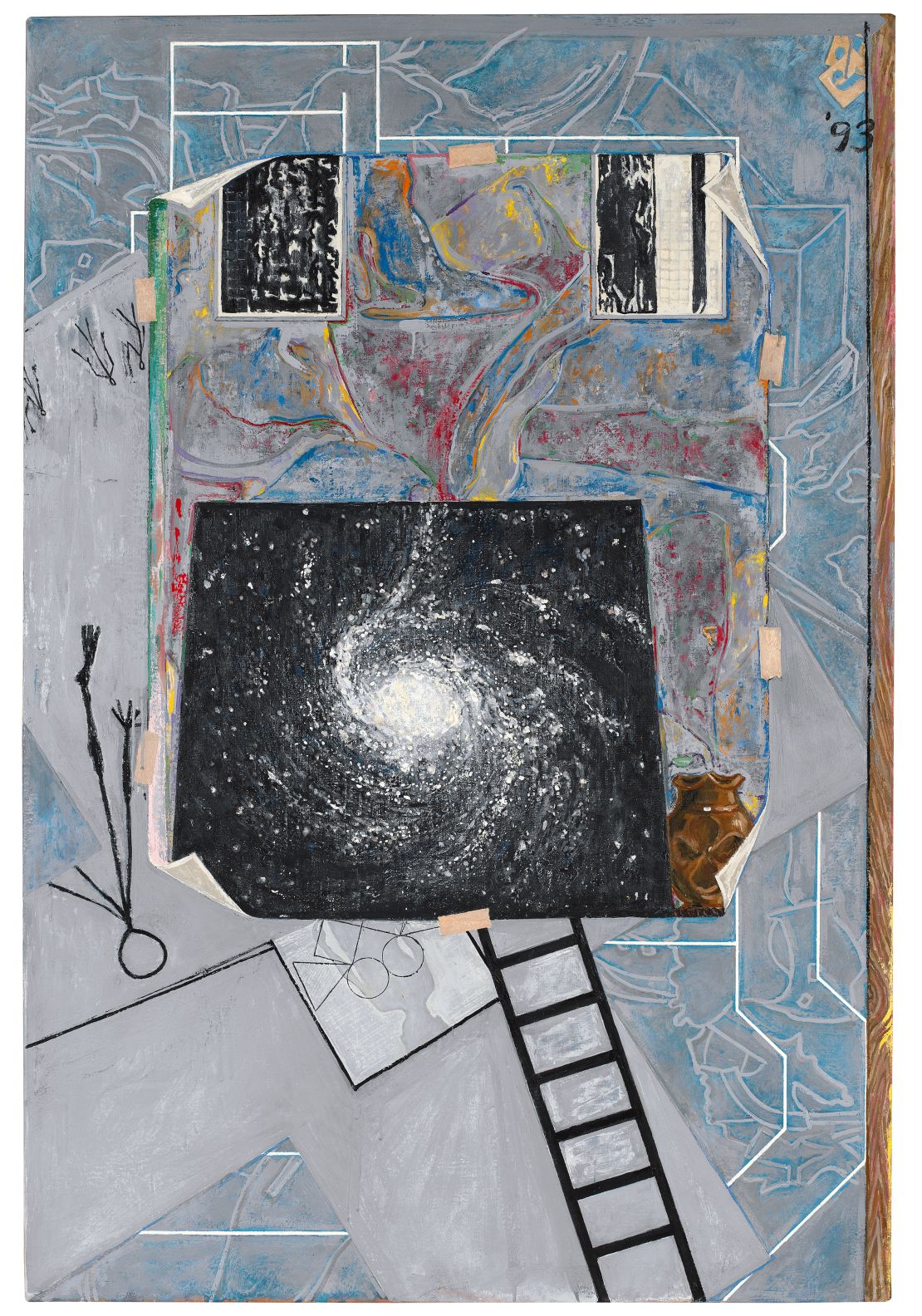

A painting of a tabletop strewn with papers, one of which depicts the white speckled whirl of a galaxy, similarly toys with our perception. The image-within-an-image presents a swirling mass of stars that contains the vast mysteries of life, yet is itself contained within a canvas.

By exploring the work of an artist who continually returns to the same symbols and ideas, “Mind/Mirror” is a journey into Johns’ own galaxy of visual touchstones, repeated across time and two physical spaces. The show’s title references the themes of doubles and mirroring that are repeated across his work.

“Our goal was to make a single show in two halves that were complementary to one another, and that the sum would be greater than the parts,” said the Whitney’s chief curator Scott Rothkopf, who staged the show with Carlos Basualdo, senior curator of contemporary art at PMA. Rothkopf writes in the exhibition catalog that Johns’ approach helped usher in a number of new movements, including Pop Art, Minimalism and conceptual art.

Time unfolding

It is rare to see such a diverse span of work from a living artist in a single show (though, as Rothkopf points out, 94-year-old Alex Katz will have a similar honor at the Guggenheim next year). Time is central to any retrospective, yet it is especially potent in “Mind/Mirror,” unfolding not just over the course of the galleries, but like invisible strings between works that were created years and often decades apart.

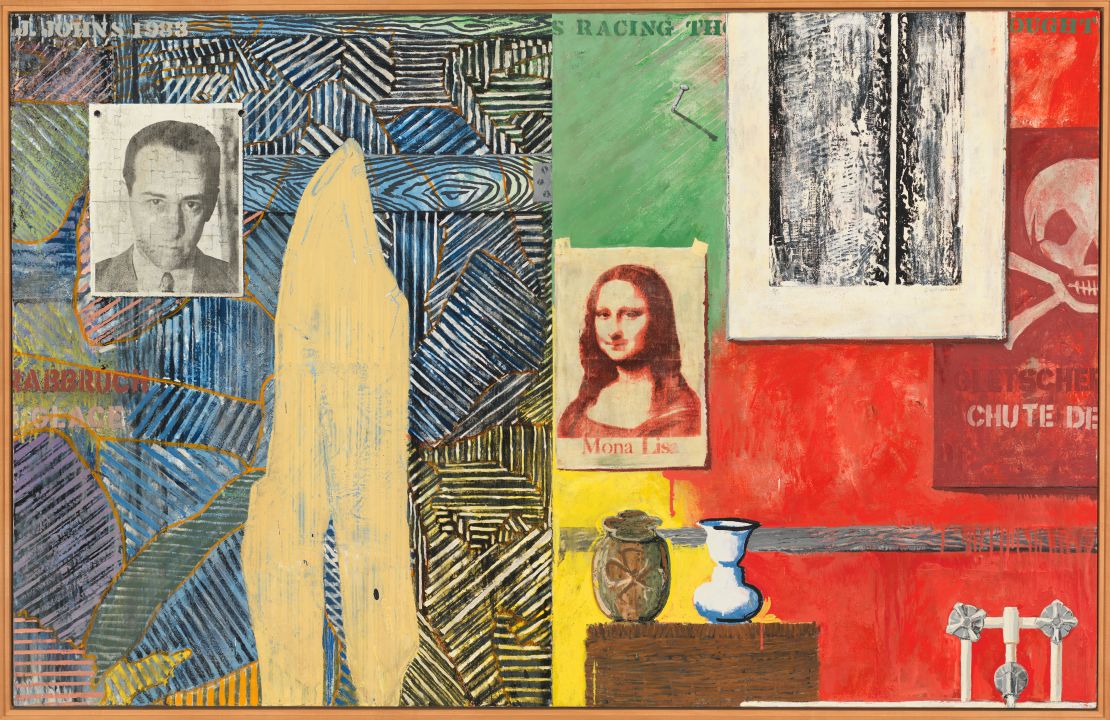

Images appear and reappear, like the “Mona Lisa,” Johns’ own wandering stick figures and the famous illusory drawing that is both a duck and a rabbit. A 2007 sculpture features a cast of choreographer and dancer Merce Cunningham’s foot hidden among a grid of aluminum numbers; the original, cast 40 years earlier, hangs uptown in Lincoln Center.

“His sense of returning to an image or an object and reconsidering it with the distance of time is an essential engine of his art,” Rothkopf said, adding that this idea is especially pertinent for those traveling to see both parts of the show. “Between these two cities, some people might have a day in between or a week or a month. And so how memory relates to perception and this passing of time, and this journey between these two places, had a parallel to some of the aspects of Johns’ art.”

“Mind/Mirror” was originally scheduled to celebrate Johns’ 90th birthday in 2020, but it was delayed by the coronavirus pandemic. Over the course of the past year, Johns said he had been “working in the studio, for the most part, on a print that took a long time,” as well as gardening when time and weather allowed. When the Museum of Modern Art in New York recently mounted a major show of Cézanne’s drawings, Johns attended, having loaned some of the works. He recalled that it was “amazing,” saying: “I wish I could have visited it again.” At the time of his own show opening last month, however, he was “at home recuperating” following a fall at his home.

Though Johns says he has no interest in the direction of his shows, he was not completely absent from the curatorial process, according to Rothkopf. In preparation for the exhibition, Rothkopf and Basualdo visited the artist every few months.

“We would talk to him about his new work, we’d share ideas, we’d ask questions, we’d look at his archive – and he was the number one lender to the exhibition,” Rothkopf explained. “Where he was less involved was that he didn’t make any specific recommendations or decisions about what the contents of the show would be, or what the ideas to be explored were. So, he really observed this notion that he’s the artist; he makes his work, and we’re the curators and our work is to make the show.”

‘He’s been miscast’

British artist Cecily Brown, who first met Johns in the 1990s and later joined the board of a foundation he co-founded in the 1960s, believes the media often misunderstands his work.

The artist’s motifs can prompt guessing games – they are sourced from art history, everyday objects, the media and his personal life, such as remembered floorplans of his grandfather’s home or a photograph from Life magazine showing the hunched form of a devastated soldier. There has also been much speculation about the “green angel,” a form he has returned to in his paintings over the decades but whose origins he has declined to explain.

“??I feel like he’s been miscast a bit about being so mysterious, like he’s some sort of Holden Caulfield figure who refuses to engage,” Brown said in a phone interview. “I feel like the work itself is what he wants you to engage with… I think the trouble with people feeling that there’s a mystery to solve is that then there’s going to be a moment where they feel like they got it. And then what happens?”

The Whitney show forges links between Johns’ art and personal life – works possibly reference the late artist Robert Rauschenberg, with whom Johns had a romantic relationship in the 1950s, while silkscreened newspaper details may allude to the crimes of his former studio assistant, James Meyer, who stole and sold his unfinished paintings. Artworks that evoke a keen sense of loss and grief fill the rooms, Johns’ own shadow looming like a spectral figure in several of the paintings.

Brown said she relates to the “restlessness” and “obsessiveness of making and remaking,” and that, even with Johns’ most emblematic works, clue-seeking through his visual lexicon isn’t the point.

“The meaning is always shifting,” she said. “The target or flag is really almost just a ground to contain this shifting meaning. And it’s a mistake to try and pin any of it (down).”

Johns first painted the American flag just ahead of the Vietnam War, two years after being honorably discharged from the Army. His flag representations have been continually mined for political meaning. But for a viewer in the 1950s, a visitor to “Mind/Mirror” today and Johns himself, the flag almost assuredly has different implications.

Brown summed it simply: “I think it’s all there for the looking.”

“Jasper Johns: Mind/Mirror,” running concurrently at the Whitney Museum of American Art and the Philadelphia Museum of Art, is on view through February 2022.

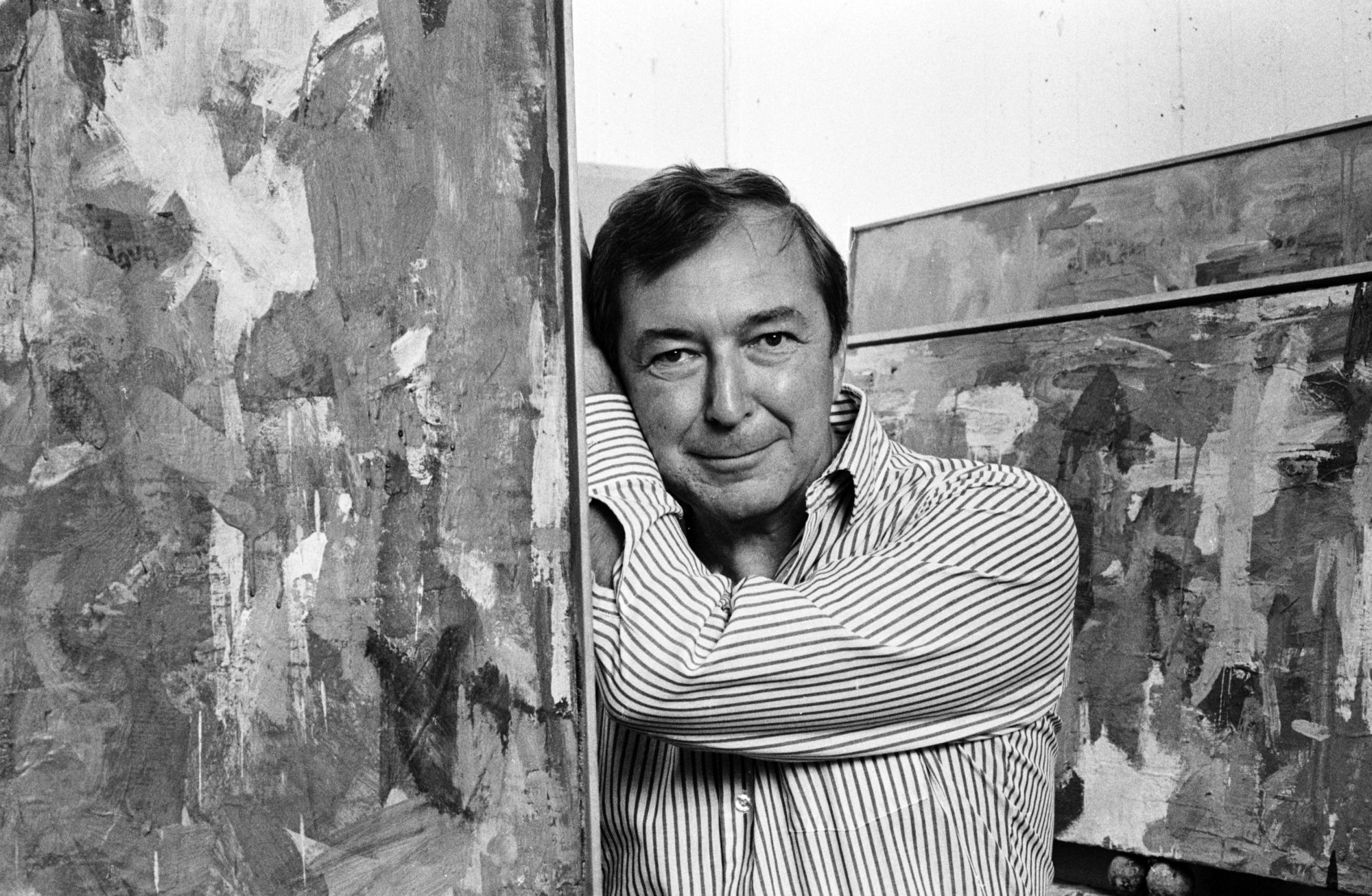

Top image: Jasper Johns photographed with his work at the Whitney in New York City, October 1977.