Few accessories have lived as complicated a life as the headscarf. The versatile fabric has been chosen by and impressed upon people for political, religious and practical purposes for centuries. It has been favored by revolutionaries and royalty alike. It can be either conservative or rebellious. Beyond its utilitarian origins as a source of protection from the elements, the headscarf remains at the center of contentious debate about women’s rights, identity, power and class.

In recent history, conversations about the headscarf have often centered on its use in Islam and the prejudice Muslim women have faced.

In 2013, Nazma Khan founded World Hijab Day – a day for both Muslim and non-Muslim women to experience wearing a headscarf. Celebrated on February 1, the initiative began in response to the bullying Khan, originally from Bangladesh, experienced growing up in the Bronx, New York. “In middle school, I was ‘Batman’ or ‘ninja.’ When I entered university after 9/11, I was called Osama bin laden or terrorist. It was awful,” reads a statement on the World Hijab Day’s website. “I figured the only way to end discrimination is if we ask our fellow sisters to experience hijab themselves.”

Throughout history, the headscarf has sat atop the heads of culture defining women – and men – from monarchs including Queen Victoria and Queen Elizabeth II to the daring flappers of the 1920s. Ranging from patterned prints to luxe fabrics to simple sheaths, the fashion item is wrapped in centuries of interpretation.

“There’s a reason why the (head)scarf has transcended time,” said Lynn Roberts, vice president of advertising and public relations at fashion outfitter Echo Design Group, over the phone from New York City. “When you’re wearing one, people pay attention.”

The order of the day

The headscarf was born out of necessity, with wearers across Mesopotamian societies using linens to safeguard their heads from the rain and sun, as well as aid in sanitation.

Head coverings were first written into law around 13th Century BC, in an ancient Assyrian text that mandated that women, daughters and widows cover their heads as a sign of piety. Headscarves were forbidden to women of the lower classes and prostitutes. The consequences of wearing the scarf illegally were public humiliation or arrest.

“There is this underlying idea of having your head covered as a way of symbolizing being a respectable person,” said fashion and textile historian Nancy Deihl of New York University in a phone interview. “The headscarf helps to control that.”

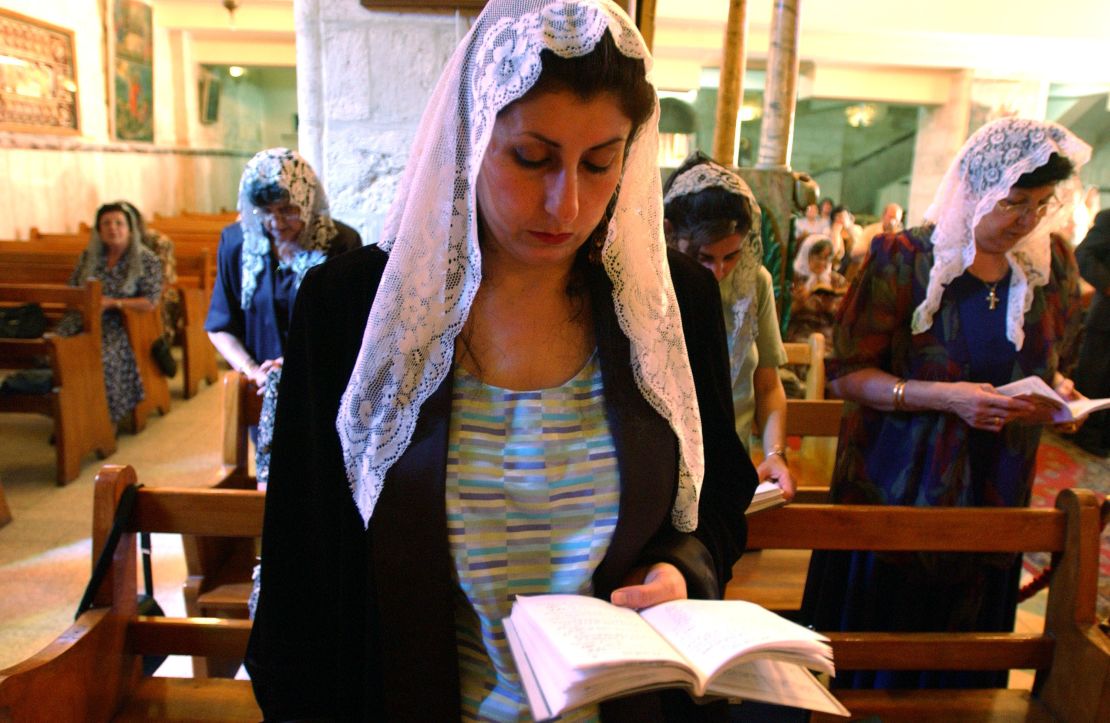

The headscarf was popularized in the religions that emerged from the region, with early Christians and Jews covering their hair with veils according to their sacred texts.

“It is disgraceful for a wife to cut off her hair or shave her head, let her cover her head,” reads 1 Corinthians 11:6-7 of the Bible. “For a man ought not to cover his head, since he is the image and glory of God, but woman is the glory of man.”

Conservative groups uphold the traditions, from Catholic nuns who wear the habit, to married Orthodox Jewish women who don the tichel (a type of headscarf) or sheitel (a wig). In Islam, the Quran’s verses about modesty have been interpreted in different ways, with some regarding head covering as obligatory and others as a choice. Political systems, geography and ethnicity also play a crucial role in how and if women choose to cover their heads.

“In Saudi Arabia, for example covering was common for women before Islam,” said Faegheh Shirazi, author of “The Veil Unveiled: The Hijab in Modern Culture.” They were already covering as more of a practical answer to the harsh climate and intense heat.”

A tool for resistance

Like the black leather jackets worn by the Black Panther Party during the US civil rights movement and the beret popularized by Che Guevara during the Cuban revolution, scarves have become ubiquitous with social movements throughout history.

In 1786, Louisiana legislators enacted the Tignon Laws, requiring Black and mixed-race women to wrap their heads in cloth.

“The law shows that there was a lot of anxiety around Black people styling their bodies. In reality, Black and mixed women had already been wrapping their hair as a marker of an identity separate from the mainstream,” said Jonathan Michael Square, a scholar of fashion and visual culture in the African diaspora at Harvard University.

In the 1970s, the Mothers of the Plaza de Mayo, a group of Argentine women advocating for information about their disappeared children, began wearing white headscarves tied under the chin, known as “pa?uelos,” as a symbol of unity and a nod to cloth diapers the women used to raise their children.

In 2004, France banned religious garments including the Muslim hijab in state schools, and in 2010 banned full-face veils in public as well. Other countries have enacted similar rules; the United Nations has stated that the ban on full-face niqab could further marginalize Muslim women and is a violation of their human rights.

The bans have been met with public protests. In 2018, organizers staged a protest in France after a mother was banned from a school trip for wearing a hijab. Last year, demonstrators in Denmark wore makeshift coverings across their faces after a law was passed banning face-covering veils in public.

A Fashion fixture

As early as the 1910s French fashion houses were dreaming up designs that included colorful, embellished scarves on the head. Fashion plates for designs by French couturier Paul Poiret show headscarves in bold patterns, sometimes affixed with a centered jewel.

Following the Women’s Suffrage movement, women began enjoying more freedom in their lifestyles and their fashion. They donned bobbed hairdos, participated in sports and fitness, and covered their hair while riding in new convertible automobiles, according to fashion historian Sarah C. Byrd. Hollywood starlets including Anna Mae Wong and Evelyn Brent were captured on and off the screen with sophisticated silk wraps or more bohemian scarves that were worn wide across their foreheads.

Hermès debuted its first scarf in 1937, with an elaborate woodblock design on imported Chinese silk. The item became a fixture in high society, worn by Queen Elizabeth II of England, American First Lady Jacqueline Lee Kennedy Onassis and Princess Grace Kelly of Monaco, the last of whom once famously used her Hermès scarf to fashionably sling her injured arm.

World War II saw the return of the utilitarian headscarf, as women in the UK and US took up jobs in factories as men went off to fight.

“In Britain in particular, scarves were useful on two levels: promoting propaganda and moral messages, as well as helping women comply with the demands of working in a factory,” said Deihl. “It embodied putting a good face forward and remaining appropriate despite being in the midst of war.”

In the 1960s, the headscarf became a go-to among political counterculture and experimental fashion movements, from geometric Mod styles to agragrian bohemian looks.

“In mainstream culture, some women wore them to protect their hairstyles – think big bouffants or straightened, styles that took some time to do,” explained Byrd. “For hippies, these could be simple printed cotton or more decorative imported textiles.”

By the late ’90s, headscarves were closely associated with hip hop and R&B. The paisley print bandana, long associated with urban gangs and cowboy culture, received a softer update with chart-toppers including Aaliyah, Jennifer Lopez and Destiny’s Child sporting embellished versions in music videos and on red carpets.

In recent years, the headscarf has been part of a resurgence of ’90s trends. Fashion houses including Louis Vuitton and Jacquemus have debuted head coverings with modern takes on classic patterns. Celebrities including Rihanna, Bella Hadid and Hailey Baldwin are fans of the style.

Social media has also spawned a group referred to as Hijabistas – hijab-wearing Muslim women who use their unique style to redefine what it means to be a modern Muslim woman.

Headscarves have remained a staple because of their versatility and cultural longevity. When women cover their hair, they are continuing a centuries-long tradition with a polarizing history of strife, style and sensation.

“Hair wrapping has stood the test of time for a reason, because it works,” said Maria Sotiriou, the founder of UK brand Silke London. “To call it a resurgence would be to say it was lost at some point – instead I think there is now, more than ever, a sharing of knowledge between cultures.”