A delegation from Easter Island is preparing to visit London to ask for the return of a huge statue from the British Museum.

The 2.5-meter basalt figure has been part of the museum’s collection since 1869 – but now the islanders want it back.

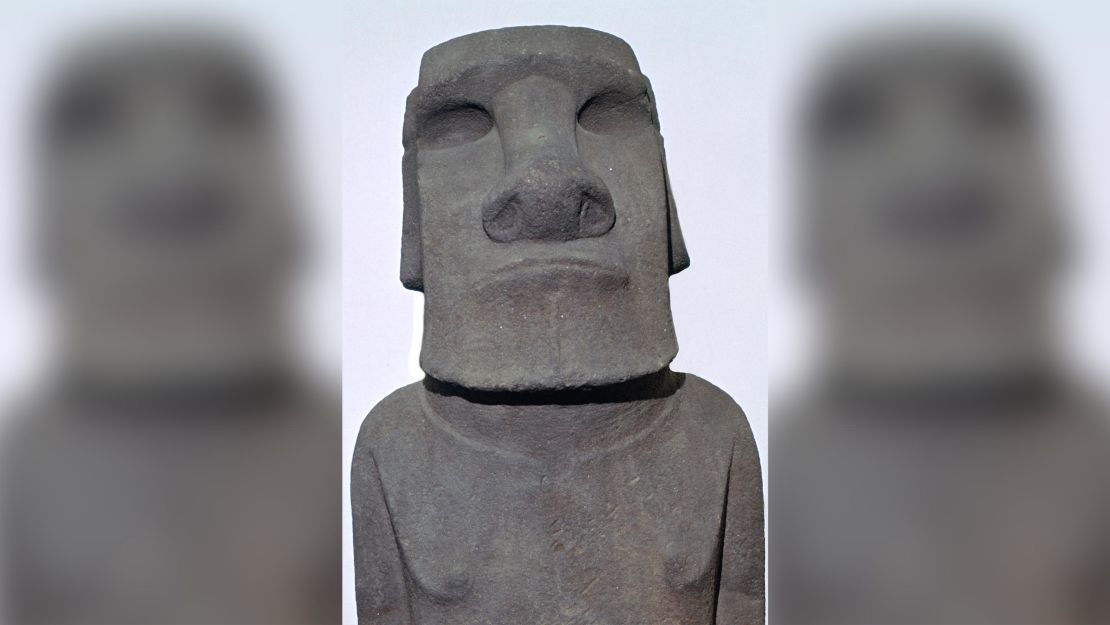

Easter Island, known as Rapa Nui in the local language and governed by Chile, is famous for the moai statues that dot its landscape.

A delegation including Carlos Edmunds, president of the council of Rapa Nui elders, and Felipe Ward, Chile’s minister for national property, will travel to London to underline the significance of the moai and discuss its future. The group will arrive in the UK capital next week, the Guardian reported.

Islanders carved the statues to commemorate their ancestors and believe that the moai are an incarnation of dead relatives. According to the British Museum, around 887 moai were erected between 1100 and 1600 A.D.

Hoa Hakananai’a – which is Rapa Nui for “lost or stolen friend” – is one of only 14 moai made from basalt, with the majority carved from softer volcanic rock. The statue is estimated to weigh about 4.2 metric tonnes.

“We very much look forward to this meeting and having an opportunity to have a discussion directly with the Rapa Nui community,” the British Museum said in a statement. “The subject of the talks would involve taking the delegation to see Hoa Hakananai’a and then discussing any future proposals they have.”

While some want the original statue returned, others have proposed a deal involving a replica moai and a financial donation from the British Museum, which would be used to protect the Rapa Nui cultural heritage, according to Spain’s EFE news agency.

Conservation is an increasingly important issue for Easter Island, with growing concerns about the impact of tourism.

Despite its isolated location in the middle of the Pacific Ocean, a five-hour flight from the Chilean capital of Santiago, the island has become a popular tourist destination.

With visitor numbers putting pressure on local infrastructure, the government in August introduced a 30-day time limit for visits.

Interest in the island was also piqued when scientists revealed that its history might be more complicated than previously thought.

For decades, researchers believed that the original population of the island destroyed itself through infighting and depletion of natural resources.

However, a study published in August showed that the society was sophisticated and collaborative.

“Ancient Rapa Nui had chiefs, priests, and guilds of workers who fished, farmed, and made the moai. There was a certain level of sociopolitical organization that was needed to carve almost a thousand statues,” lead study author Dale Simpson Jr., an archaeologist at the University of Queensland, said in a statement at the time.