‘You have no idea how important it is to feel that someone cares about you’: Inside a pioneering school for transgender students

By Diego Jemio, for CNN

Buenos Aires, Argentina — Lariana Guerrero Lera was born in Salta, a province in northern Argentina that has some of the highest poverty rates in the country. She was assigned male at birth but tells CNN that even as a five-year-old, she didn’t feel like a boy.

Both school and home life were difficult for Guerrero. She didn’t fit into the conservative society around her and says her father stopped talking to her the day after she wore a dress to a party.

“I come from a conservative Catholic family. Elementary school was an extremely hostile environment back then,” Gurrero says, calling the “harassment” she experienced “overwhelming.”

So, at 16, not wanting a confrontation with her father and wanting greater freedom and community, Guerrero moved to Buenos Aires, Argentina’s bustling capital. With no formal education or trade skills, she took up sex work to survive.

Then one day a transgender friend told her about a school she was attending that she thought could help other people like herself and Gerrero get their high school diploma as adults.

Lariana Guerrero Lera described school in her hometown, as a child who knew she was different, as “a hostile environment.” Nicolas Borojovich

“We were touching up our makeup in a cab, driving through the red-light district… that’s when I started considering the possibility, [of going back to school],” Guerrero says. She was 25 years old at the time.

It took Guerrero a year to act on the tip her friend had given her. At the time of writing, the 27-year-old, who now identifies as a transwoman, was one of 290 people studying at the Bachillerato Popular Travesti, Trans y No Binarie Mocha Celis, the first-known high school in Latin America for trans students.

An educational and cultural hub for the transgender community

Mocha Celis, as it’s typically called, opened its doors in 2011, the year before Argentina’s Gender Identity Law was passed. The Law is a groundbreaking piece of legislation that grants all individuals over the age of 18 the right to change their legal gender identity without undergoing gender affirmation procedures.

The institution was named after Mocha Celis, a trans woman who never graduated from high school and whose 1995 killing in Buenos Aires remains unsolved. Starting with a cohort of just 35 students, the facilities were modest, with classes held in a boxing gym.

“In the early days, we actively sought potential students in areas where sex work was prevalent, such as hotels and other establishments where we knew they might be,” recalls Virginia Silveira, a graduate of the institution who now teaches research techniques a few hours a week at Mocha Celis.

Virginia Silveira came to Mocha Celis as a student and now teaches at the institution. Nicolas Borojovich

Today, Mocha Celis is a free public school – which, according to a case study on it published by the UN, takes in more than 100 students a year between 16 and 60 years old, and offers an official curriculum, taught through a gender-sensitive lens. Its diplomas are nationally recognized, and the institution relies mainly on state funding though it also accepts public donations. As well as offering diplomas, Mocha Celis runs numerous other projects aimed at eliminating the various barriers that trans people face, with services ranging from job training to finding work placements and offering emotional support.

“Beyond being a school, we aspire to be an educational and cultural hub for the transgender community,” Francisco Qui?ones Cuartas, one of the founders of Mocha Celis tells CNN. “The driving force behind this school was to respond to a population that was persecuted. We wanted to reverse that situation, starting with education. We are immensely proud of the history we have built.”

Many students affectionately call it the “school of tenderness” because it represents so much more than a traditional educational institution.

The school aims to be inclusive – admitting students from other marginalized groups such as single moms, afro-descendant people, indigenous people or people living with disabilities – but it specifically exists to respond to a history of discrimination against transgender and non-binary people in Argentina.

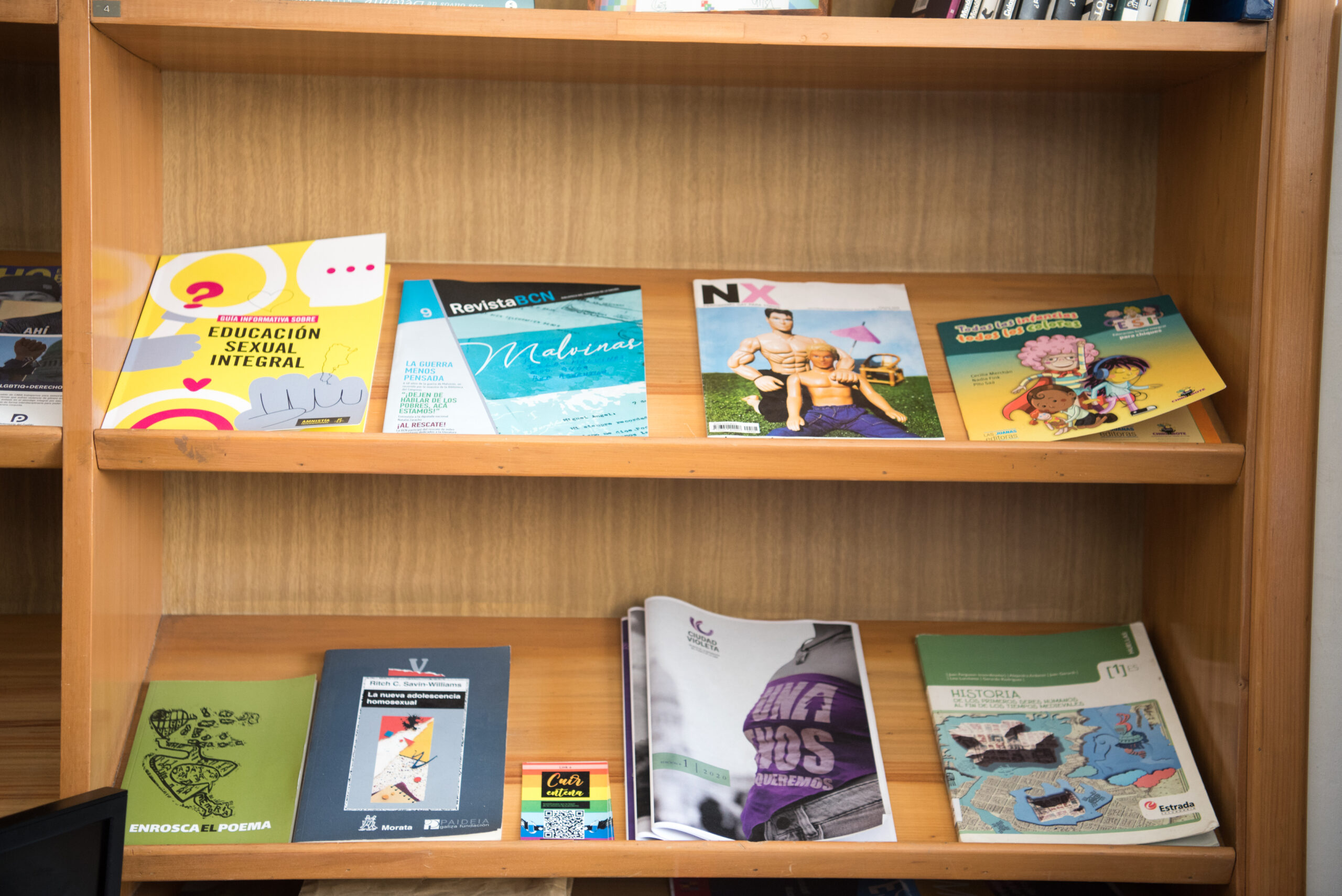

Reading material on sex and sexuality education on display at the Mocha Celis school in Buenos Aires. Nicolas Borojovich

According to a 2023 study conducted by the Mocha Celis and by the Public Ministry of Defense, this community is still denied fundamental rights including access to education, healthcare, decent housing, and employment opportunities. The report outlines how trans people in Argentina suffer great difficulties in obtaining formal and dignified employment due to stigmatization, discrimination and low levels of education. It also details personal accounts of arbitrary detention and mistreatment by the police.

“I had never dared to finish high school due to discrimination. Mocha Celis is a space where I feel comfortable, free from judgement, and where I find teachers who understand me,” Guerrero tells CNN. “It is the starting point for dreaming about the possibility of a different life because I used to believe that I would die doing sex work.”

‘I learned about the right to education and felt welcomed. When that happens, you become motivated to fight for more rights that you now know are yours.’

Many students arrive at Mocha Celis disheartened by their previous experiences within the education system, where they say they endured mistreatment, harassment, and violence. Many tell CNN they faced discrimination when attempting to use restrooms, regularly heard derogatory comments, or were even expelled from school. As a result, the school does more than educate, it affirms its students on a human level.

Manu Mireles, a teacher and the school’s academic secretary recounts what one student told him of their experience: “One student told me this is the first time that an institution looks me in the eye, calls me by my name, and treats me with respect.”

The school is in the Balvanera neighborhood, located in the center of the Buenos Aires. It occupies a two-story building owned by the Ministry of Education. There, the atmosphere is one of study and camaraderie. Some students also find an opportunity to start enterprises, such as one initiative that trains transgender people how to provide care for the elderly.

Mocha Celis is the first-known high school in Latin America to help trans adults earn their high school diploma, but it also takes in students from other marginalized backgrounds. Courtesy Luciana Leiras/Mocha Celis

Guerrero tells CNN about the jobs she is currently holding down, as a dog walker and an employee in a small cooperative that produces shoes and clothing for transgender community. She also tells CNN that it took her time to adjust to being in a learning environment.

“When I started studying, I was quiet and passive. But with each passing class, I wanted to know more. Now I want to learn about administration and accounting. The excitement of learning has engulfed me,” Guerrero says.

Despite progressive legislation in the form of the Gender Identity Law and a Trans Labor Quota (which establishes a minimum requirement of 1% representation of the trans population in public administration) trans people are still far from equal, according to separate research published by Argentina’s Ministry of Public Defense and the Public Policy Implementation Center for Equity and Growth (CIPPEC).

CIPPEC, a non-partisan think tank that works to improve public policy, reported in 2020 that transwomen in Argentina had a life expectancy of just 37, compared to an average of 77 for the rest of the population. The organization called them “the most vulnerable population group” in the country. According to the report, there are many reasons for the high mortality rate including limited access to healthcare, HIV prevalence, exposure to violence from both the public and the police, and suicide.

For Mocha Celis, sustainable funding remains a challenge. The institution’s academic secretary Manu Mireles tells CNN that the costs that the Ministry of Education doesn’t pick up are the ones that enable the institution to offer the supplementary services it does.

“The next challenge is to get the Ministry of Education to pay for all the positions involved in space management,” Mireles says. “At the moment, they pay for the teaching positions and some management positions. But the ministry does not pay a few others, such as the support teams. They are essential for our proper functioning.”

After graduating from Mocha Celis, Virginia Silveira became the first person of any gender in her family to attend university. Nicolas Borojovich

As for the future, the November 2023 presidential election of far-right libertarian Javier Milei, might be a cause for concern for trans rights more broadly, and Mocha Celis specifically.

Among his first acts after taking up office on December 10, Milei eliminated the Women, Gender and Diversity Ministry and threatened during his presidential campaign to eliminate sex education in schools.

And so the future might be uncertain, but for now, Mocha Celis continues to change the lives of its current students like Guerrero, and past students like now part-time teacher Silveira.

Silveira tells CNN that with the support of her classmates and teachers at Mocha Celis, she became the first person – of any gender – in her family to attend university, where she’s studying law and working part-time in counselling and victim support at the Public Prosecutor’s Office.

“Through Mocha Celis, I learned about the right to education. I always felt welcomed and supported” she says. “When that happens, you become motivated to fight for more rights that you now know are yours, such as access to decent housing, employment, and healthcare.”

“You have no idea how important it is to feel that someone cares about you.”