‘What if I’m going to die?’ Bianca Balala risked it all to get a body that matches her gender identity

By Mailee Osten-Tan and Prim Chuwiruch Corben for CNN

Mindanao, Philippines and Bangkok, Thailand — By 8:30am on April 27, 2023, the Pratunam Polyclinic in Bangkok was already full. Women sitting in rows of plastic chairs occupied most of the already cramped reception area. An empty fish tank with dirty water stood in one corner of the room and a receptionist snapped instructions in broken English in the other.

It is here, according to the owner of the clinic, that hundreds of transgender women, from across Asia and further afield, come every year, hoping to get an anatomy that better reflects their gender identity – at a fraction of what it costs elsewhere.

On that Thursday, 29-year-old Bianca Balala from the Philippines was one of them. After years of “being trapped in a wrong body,” and working to save up the money for a gender affirming vaginoplasty, Balala finally took what she called the “longest journey of my life.”

The 12-hour trip started when she took a bus from her rural hometown in southern Philippines to Pagadian City, where she caught a flight to Manila. The next day, she boarded another plane to Bangkok. Balala checked into a hostel once she arrived, and four days later, she walked a short distance to the Pratunam Polyclinic, feeling nervous but determined.

A staff member handed her a dressing gown and gestured for her to get changed in an adjacent room with yellowed newspaper clippings of women in lingerie and before-and-after breast surgery pictures were taped to the walls. Then she was led up three flights of narrow stairs to a windowless operating room. After she lay down on an old operating table, her arms were strapped by the wrists to a narrow wooden plank placed horizontally under her upper back.

Listen to this woman who says she risked it all for gender affirming surgery

The small operating room was stuffed with random items, including a VCR, and empty boxes of breast implants were stacked up to the ceiling, Balala told CNN. The sight “shocked” her because it didn’t look like anything like an operating room.

Despite being told to leave all her belongings at the reception desk, she said she snuck in a pink rosary in her dressing gown pocket. Her mother had pressed it into her hands as they waited for the bus that would take her on a trip that would mark the end of one chapter of her life and the beginning of another.

“My heartbeat was so fast,” Balala told CNN. “I was just thinking, what if bad things happen to me?” Balala began to pray.

The reception area of Pratunam Polyclinic, Bangkok, in July 2023. Watsamon Tri-yasakda for CNN

Pratunam Polyclinic, opened in 1988 by Dr. Thep Vechavisit, has built a reputation, according to media reports, as a low-cost destination for gender affirming and cosmetic procedures including breast augmentation, nose jobs, and vaginoplasty, which involves rearranging genital tissue to create a vagina and vulva.

Balala told CNN that she was quoted $7,300 for a vaginoplasty by a clinic in the Philippines. In Thailand, few clinics publicly disclose their pricing. But one plastic surgeon in Bangkok charges between $6,500 and $12,000, depending on the surgical technique, according to his website. Another clinic in the Thai capital says the cost can vary from $10,000 to $17,000. But Pratunam Polyclinic offers vaginoplasty using the penile inversion technique for just $2,065.

Dr. Thep, as everyone calls him, said he performs roughly 350 vaginoplasties every year. Most of his patients are from Thailand but about 20% travel to the clinic from other Asian countries, including: India, China, Indonesia, Malaysia and the Philippines. They come despite the discrimination they face and the lack of healthcare support for transgender people in their home countries.

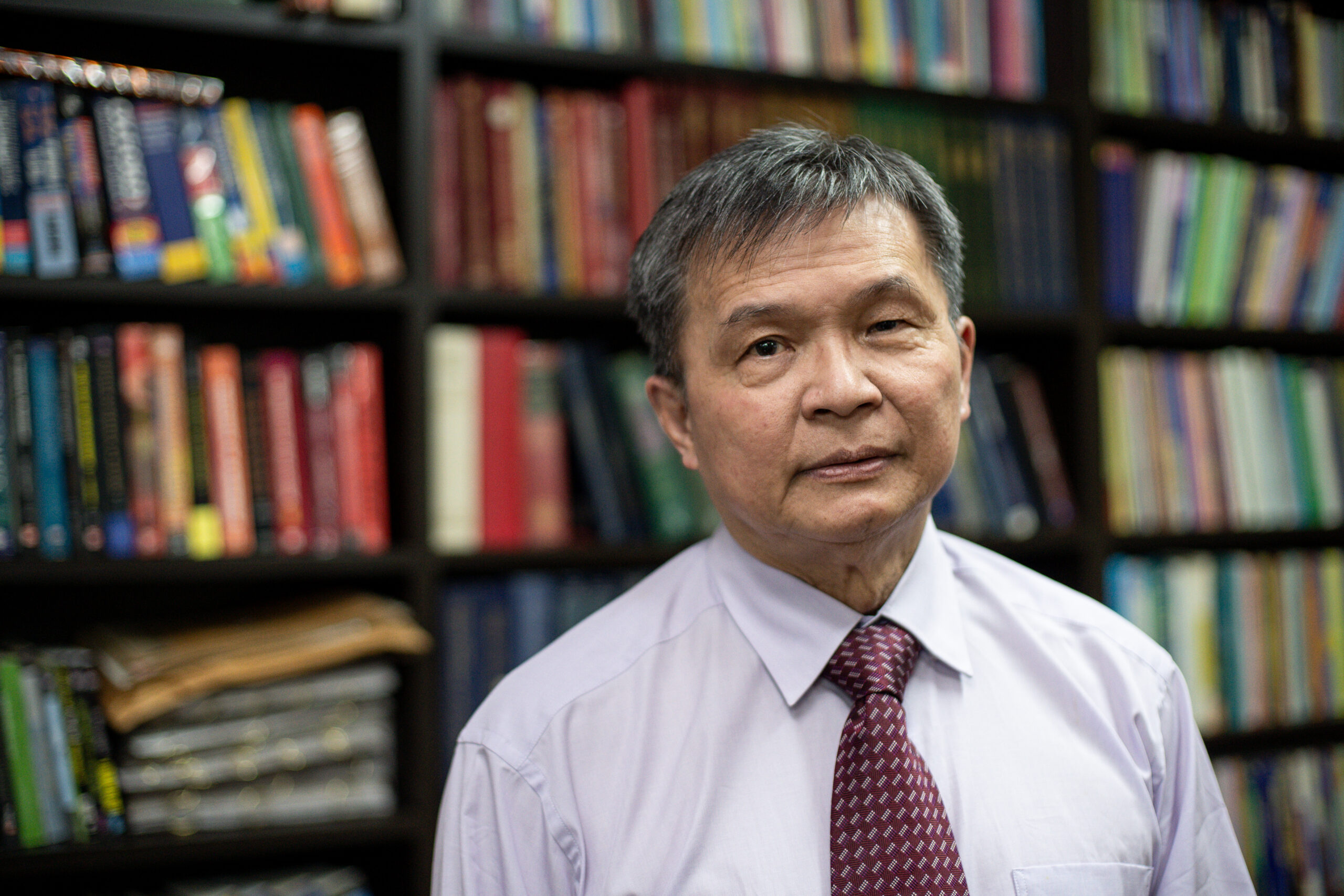

“People come to see me for my skills, not because of what my clinic looks like,” said Dr. Thep Vechavisit, 71, who founded and runs Pratunam Polyclinic. Watsamon Tri-yasakda for CNN

In the case of the Philippines, the national health insurance program, PhilHealth, does not currently cover gender affirmation surgeries for transgender people, said Dr. Albert Domingo, deputy spokesperson for the Philippine Department of Health.

Balala had known about the Pratunam Polyclinic’s low-cost surgeries for some time but said she had initially been reluctant to go to Dr. Thep. She told CNN that she’d heard mixed reviews. Some of his patients had been happy with their operations, but others said they’d experienced medical complications or been unhappy with the results of their surgeries, because they weren’t aesthetically pleasing. There were also complaints about the rudeness of the clinic’s staff.

But Balala would soon change her mind.

“I risked everything to go”

Balala was assigned male at birth. When she was around five years old, she remembers wrapping a handkerchief around her head to mimic long hair and telling her grandmother, “This is my hair. I am a woman.”

Her mother, Juhanna Balala, told CNN that she let Balala be. “She has always been my daughter.” Despite their strong Catholic faith, family members helped Balala accept her gender identity as she grew up.

Having heard mixed reviews about Dr.Thep, Balala held on to her faith as she underwent surgery at his clinic in Bangkok. Mailee Osten-Tan for CNN

As a teenager, she started to participate in local trans beauty pageants. Exposure to older trans beauty queens, who had undergone surgical transitions, made Balala think about getting gender affirming surgeries herself. “I wanted to have the surgery to become more confident in my body. It was really hard for me to have the male part.”

Not all people who identify as trans or non-binary feel they need surgery, but for some, the gender dysphoria or discomfort caused by the incongruence between their physical bodies and gender identity, can take a heavy mental and emotional toll. Globally, according to a 2023 review and meta-analysis of 65 selected studies, the prevalence of suicidal thoughts and attempted suicide among transgender people over their lifetime was 50%, and 29% respectively, and nearly half of the transgender people who had suicidal thoughts did end up taking their own lives.

Despite the distress Balala’s body caused her, the cost of a vaginoplasty was much more than she could afford. She said a clinic in Manila had quoted her $7,300 for the procedure.

But Balala lives hundreds of miles away in the southern Philippines, where the incidence of poverty among families in the province was estimated at around 44% in the first part of 2023, according to official government statistics. Most people in her rural hometown support themselves through farming or run small businesses. Balala sold husky puppies and, occasionally, sex online. “I hate to say it but it’s part of survival,” she told CNN.

According to Naomi Fontanos, a trans activist and founder of Gender and Development Advocates Filipinas, a non-profit organization campaigning for trans rights in the southeast Asian country, “A lot of trans women in the Philippines do cybersex” because workplaces continue to discriminate against trans job applicants or insist that they present as the gender they were assigned at birth.

Balala now feels more confident in her body. Mailee Osten-Tan for CNN

Despite saving whatever money she could, Balala thought she was out of options until her friend Lana made her an offer that was hard to refuse. Lana, whose name has been changed to protect her identity because she doesn’t identify publicly as transgender, had found a package for less than half of what Balala had been quoted in the Philippines. The online deal included a vaginoplasty, travel arrangements and nearly a month of accommodation with caregivers in Bangkok for just $3,200, said Balala. The only part that concerned Balala: the surgery would be with Dr. Thep at the Pratunam clinic. But Lana would be going too and even offered to lend Balala the $600 she needed to bridge the gap in her savings.

Worried but excited, Balala said yes. “I was really nervous. I heard a lot about ladies who had problems in their surgeries. I was worried what if I’m going to die? but I still went because it was my dream to have that surgery,” she told CNN. “I risked everything to go.”

A frugal doctor

Dr. Thep, 71, lives next door to his four-story clinic where he is the only surgeon. With a flush of pride, he told CNN that he’s performed at least one vaginoplasty every single day since 1998 when he first started offering the operation, and that he never takes a day off work. “How could I close on any given day?” he said. “It’s my own clinic on the line!” He also rarely stops for lunch, subsisting instead on cartons of chocolate milk.

When asked why he keeps his prices so low, Dr. Thep said: “I know what it’s like to not have money,” alluding to his humble beginnings. He said he grew up poor in a family where his parents didn’t encourage him to study. The low-cost surgery at his clinic also ensures a consistent influx of patients. As a result, he said, the clinic has always been profitable.

Dr. Thep told CNN that he keeps costs down by maintaining a basic infrastructure at the clinic, keeping staff numbers lean, minimizing the operational overhead, and spending money only on what’s essential. “People come to see me for my skills, not because of what my clinic looks like,” he said.

To illustrate how his surgical prices compare to other clinics, Dr. Thep matter-of-factly compared his work to “a plate of fried rice:” “At some auntie’s shop along the side of the road, it will cost 50 baht ($1.40), at a coffee shop it’s 200 baht ($6), and at a 5-star hotel it’s 300 baht ($8.30).” Prices depend on where the service is offered and what else is offered alongside the service, he told CNN. “It doesn’t mean that auntie’s fried rice is inedible.”

To offer his services as cheaply as he does, Dr. Thep also uses a local anesthetic combined with sedatives to perform the vaginoplasty, instead of general anesthesia, which would need to be administered by an anesthesiologist.

“I don’t think general anesthesia is needed for vaginoplasty. Local anesthesia with sedation is safe for patients,” Dr. Thep told CNN, adding that hiring an anesthesiologist would add “at least 30,000 baht ($800) to the surgery cost.”

Dr. Thep at his clinic in Bangkok. Watsamon Tri-yasakda for CNN

But Dr. Jess Ting, a surgeon with New York’s Mount Sinai Center for Transgender Medicine and Surgery told CNN, “It is uncommon to do major gender affirming surgeries under local anaesthesia,” Dr. Ting, who was referred to CNN by the non-profit World Professional Association for Transgender Health (WPATH), wrote in an email, “General anesthesia allows the patients to be free of pain during these intricate and prolonged operations. Anesthesiologists play a vital role in the operating room monitoring the vital signs of patients and ensuring that they are adequately anesthetized, so they don’t experience unnecessary pain.”

Likewise, Dr. Chettawut Tulayaphanich, who has been doing gender affirming surgeries in Thailand for 25 years, told CNN that he would never recommend vaginoplasty under local anesthesia unless his patients had a pre-existing condition that would make general anesthesia unsafe.

A 2021 review of the considerations for anesthesia used in gender affirmation surgeries said there was a growing need for doctors to look for more effective modes of anesthesia to improve surgery outcomes. General anesthesia and local anesthesia with sedation are both used in gender affirmation surgeries, the review stated, but the choice of which mode to use should only be made after a “cautious evaluation” of the surgical procedure and a discussion of the patient’s expectations.

WPATH’s guidelines recommend that surgeons provide patients with detailed pre- and post-operative consultations, including an explanation of potential consequences, while being sensitive to local cultural realities. Balala, and two other patients who spoke with CNN but were not comfortable revealing their transgender identity publicly, said they received very little consultation from the doctor or nursing staff throughout their experience.

When asked whether he offers detailed consultations to his patients, Dr. Thep said: “As long as patients have a certificate from psychiatrists, one of whom should be from Thailand, clearing them for the surgery, I go ahead with the surgery.” He added that he prescribes “lots of rest” after the surgery.

Patients rest after undergoing surgical procedures at Dr. Thep’s clinic. Watsamon Tri-yasakda for CNN

Balala, who acknowledges that she didn’t ask any questions of Dr. Thep, remembers being “awake, but eyes closed” during the procedure. She said she sometimes felt pain and could hear the nurses chattering around her. A series of thoughts was running through her mind.

“What if there are complications? What will happen to my family? What will happen to my dogs?”

After about two and half hours, Balala was wheeled off into a cramped recovery room and transferred onto a narrow, stiff bed chair, which she told CNN was “very uncomfortable.” When she asked for her phone, she said, a clinic employee shouted at her, “Shut up! Sleep! Shut up!” Only a few of Dr. Thep’s employees speak English well, so their communication with patients tends to be curt.

Dr. Thep said that he is aware of these complaints but they don’t bother him. “I am not in the market to run after patients like other clinics do who lure patients with sweet language,” he said, adding that sometimes he tells his staff to learn English but many of them don’t, and he doesn’t force them because most of the time he is around to talk to patients and “these days most patients anyway have smart phones and we use google translate to communicate with each other. It is no problem.”

When Balala eventually got her phone 24 hours later, she called home crying, telling her mother Juhanna that she was uncomfortable in the bed chair, that the staff was rude, and that she was worried about post-surgical healing. Later, Juhanna told CNN that she wondered at the time whether her daughter was in good hands.

Aftercare courtesy of a hostel that was once a cafe

Balala and Lana had booked their medical tourism package through Fukelya, a hostel owned by a social-media savvy Filipino entrepreneur, Simon Po II. After spending three nights at the clinic, Balala was taken to the hostel to recover. It was just five minutes away from Dr. Thep’s clinic. Lana who had her surgery a day later, joined Balala at the hostel on the following day.

Opened in 2022, Fukelya was once a café. An empty cake fridge and bar counter remain on the ground floor. It is one of several businesses that have sprung up around Pratunam Polyclinic to meet the demand for post-surgery accommodation and aftercare. Though none of these businesses are formally connected to Pratunam Polyclinic, Dr. Thep told CNN he advises his patients to stay close so that they can return for routine check-ups and antibiotics every morning for two to three weeks.

Simon Po II prepares beds for Dr. Thep’s patients who will recover at his hostel, Fukelya. Watsamon Tri-yasakda for CNN

When CNN toured the hostel in the summer of 2023, the rooms at Fukelya were laid out like dormitories. Each bed had an emergency button that patients could press to call a caretaker to bring food or other supplies, help them walk to the toilet, or deal with emergencies. Buckets were placed between each bed for patients to empty their own catheter bags. None of the staff at Fukelya were medical professionals, but Po hired a nurse who came by, once a week, to check the patients’ vitals and change their bandages – though these services are also provided at the clinic. If a patient showed signs of distress, Fukelya’s staff contacted the clinic directly, Po explained.

Complications and compromises

The recovery process was fraught. Balala waited anxiously to see if her surgery had been a success and if she’d heal without any complications. She repeated a phrase one of her friends who’d had surgery at the clinic told her: “Don’t expect too much.” For Balala and other trans women CNN interviewed, a “good enough” vulva was much better than the distress of gender dysphoria.

But Balala worried. She’d heard stories of operations gone wrong and had seen it for herself when, one day, the woman lying next to her in the clinic “pooped from (her) vagina.” She had developed a rectovaginal fistula, when a hole forms between the rectum and vagina. It occurs in 2% to 17% of vaginoplasties.

“These cases happen, and no surgeon can claim that they never had a case of fistula,” Dr. Thep told CNN, adding he has had “very few” cases of patients developing fistula, and when they do he said: “I treat them for free.”

Dr. Alvin Jorge, who runs Cosmedics, a Manila-based clinic, said that as many as 20 women, who had received vaginoplasties at different clinics in Thailand, approached him every year with various complaints. Without specifying which clinics they came from, he said their problems included difficulty urinating, the death of labial tissue, narrowing of the neo-vaginal canal which can make penetrative sex difficult, and displeasure at how their vulvas looked.

Bianca Balala recovers after undergoing surgery at Pratunam Polyclinic on April 27, 2023. Courtesy Bianca Balala

At Fukelya, Balala said she killed time watching Netflix, listening to music, or scrolling through social media. A week after her operation, she saw her vulva for the first time at the clinic during a check-up. She told CNN she immediately called her mom. “I told her I am happy. I am happy because I am fully a woman.”

After spending about three weeks in Thailand, Balala returned to the Philippines. Juhanna greeted her at the airport with a large bouquet of flowers. Back home, she has tried to avoid any strenuous activity as Dr. Thep recommended. But she told CNN she has found it hard to follow another of the doctor’s instructions: making sure she washes herself with clean water, which is difficult as the family home has no bathroom or access to clean water. They usually wash out in the open, with water in buckets, collected from community taps, and buy drinking water.

Despite this, Balala has healed well and told CNN she is excited about being able to wear leggings, short skirts, and a bikini without hesitation. “I always wanted to wear sexy clothes and feel sexy in my body.”

Bianca displays her beauty pageant sashes and photos at her home in the Philippines. Competing in trans pageants gave her a sense of pride in her identity. Mailee Osten-Tan for CNN

The day CNN went to see Balala in the small pink house she shares with four family members, two of her aunts had come to visit and the family sat gossiping under a soursop tree, eating lechon, a Filipino speciality of pork belly slow roasted on an open fire. Balala held a small dog in one hand and gesticulated wildly with the other at her young cousins who were prodding tadpoles in the pond. The struggles she faced to get to Thailand and the fear that gripped her occasionally while she was there are now only a hazy memory.

She is full of gratitude for the Pratunam clinic and said she’d recommend Dr Thep – who many of his patients call “father Thep” – to other trans women like her.

“Dr. Thep fulfilled the dreams of the transgender [people],” she said as she relishes having what she had so long wanted. “I wanted to have surgery not just to become a woman. The main goal is to be free. To free ourselves.”

If you or someone you know might be at risk of suicide, you can reach out for help by calling these numbers:

In the US, you can call or text 988-The Lifeline provides 24/7, free and confidential support for people in distress, prevention and crisis resources.

For support outside of the US, a worldwide directory of resources and international hotlines is provided by the International Association for Suicide Prevention. You can also turn to Befrienders Worldwide.