The best amp simulators we tested

Best amp simulator for most guitarists: Strymon Iridium Effect Pedal

Best budget amp simulator: NUX Amp Academy Guitar Pedal

Best amp simulator app: Native Instruments Guitar Rig 7 Pro

The latest guitar amp simulators can give you pro-quality tones without the fuss of setting up heads, cabinets or microphones to capture your sound. And since they’re more affordable than even, they’re perfect for home recording and practice, letting you concentrate on your sound while keeping the peace with your family, friends or roommates.

To find the best amp simulator for your practice and recording needs, we called in a dozen popular models and then played, practiced and recorded with them for months. While we think all these devices sound great, after putting them to the test, we’ve found the best ones for your specific playing, practicing and recording situation.

The Iridium is the best known, most popular amp modeling pedal, and it's easy to see why. It’s simple to use, flexible enough for any playing or recording situation and sounds great.

Packing a surprising number of useful features under the hood at half the price of the competition, the Amp Academy is a great choice for anybody looking for a good-sounding, flexible amp modeling pedal on a tighter budget.

The latest update to the venerable amp modeling software, Guitar Rig 7 Pro adds useful new amps and effects to an already expansive palette, sounds great and lets you build any guitar or bass rig you can imagine — and costs less than anything similarly capable.

Best amp simulator for most guitarists: Strymon Iridium Effect Pedal

$399 at Sweetwater and Amazon

The Strymon Iridium is likely what most guitarists think of when they think of an amp simulator pedal — quick access to classic tones in a convenient package that works well on a pedalboard, on a desk for recording or on its own for practice. The Iridium is a popular tool for musicians of all skill levels, from home hobbyists to studio pros, and it’s easy to see and hear why. It’s simple to use and sounds great without any tweaking at all, and even though it’s got a very straightforward feature set, it’s easy to configure to suit your needs.

The amps sound great, which is unsurprising if you are familiar with other Strymon gear. A front panel switch gives you simple access to three models: “Round,” which approximates a Fender Deluxe; “Chime” for AC30 sounds; and “Punch” for Marshall Plexi sounds. Whichever you choose, you first run through Strymon’s analog preamp front end, which gives you solid overdriven tones and plenty of headroom for clean sounds.

The nine onboard cabinet IRs (three slots per amp model) are likewise very, very good-sounding choices, ranging from a 1-inch-by-12-inch cabinet for the deluxe up to a Marshall 8-inch-by-12-inch cabinet if you need to get (virtually) loud. Should you dislike the onboard cabs you can replace them with your own IRs via Strymon’s app; IR loading is simple, and the Iridium can load long, high-resolution impulse responses (up to 500 milliseconds at 24 bit, 96kHz)?for very realistic (or unrealistic, if you prefer) tones.

Overall, the sound palette tends toward vintage tones. You get lovely, very usable interpretations of the classic Fender, Vox and Marshall sounds, and the tone and drive controls act just the way you’d expect. (That works per model as well. For the Chime model, the mid control is repurposed as a treble cut control, as you’d expect to see on a Vox AC30.) You don’t get amp reverb or tremolo circuits, however, and there’s no effects loop. That said, this isn’t really a heavy-gain device, so you should be fine running your time-based and modulation effect either before or after the Iridium (we tried both) for good results.

A “Room” control gives you just that. It’s another IR stage, with a choice of small, medium and large spaces and a level control. It’s simple and sounds good. It’s not amp reverb and doesn’t try to be (though it might have been nice had Strymon added a spring reverb sim), but it provides a pretty convincing approximation of amp-in-a-room tone.

The Iridium can run in stereo. You get left and right outputs, while the single input jack is a TRS jack, meaning you’ll need an adapter if you’re running both outputs of a stereo instrument or pedal or preamp into it. You can’t, however, run different amps or cabinets left and right as you can with the Walrus ACS1, DSM & Humboldt Simplifier or Boss IR-200. You can also sum the stereo input into mono via a rear panel switch; if you do that, both outputs give you a mono output — convenient as a splitter if you don’t need a true stereo image.

Despite the simple onboard controls, you can save up to 300 presets within the Iridium. You just can’t access more than one without an external controller. Strymon’s own MultiSwitch can be used to access three presets, or you can select from the full complement of 300 using a MIDI controller such as the Morningstar MC8 that we used in testing. MIDI input is via a 1/4-inch TRS jack that doubles as an expression pedal input (you can assign it to any parameter or use it as a volume control) or connector for the MultiSwitch.

The Iridium isn’t perfect. While there’s plenty of gain on tap here in the Punch model, it isn’t oriented toward modern sounds and you may want to think about something else if you’re in pursuit of tight, high-gain metal sounds. An effects loop would be a nice addition for pedalboard management purposes and for those who like effects between the amp and output stage.

The Strymon Iridium sounds great, and it’s dead simple to use, which is why you see it on so many pro and enthusiast pedalboards. It’s hard to get a bad sound out of it, and playing through it really feels like playing through a good amplifier. It doesn’t offer quite the range of options and features that some of the more recent competition does, but it is still a very compelling choice for anyone looking to replace or complement an amp.

Best budget amp simulator: NUX Amp Academy Guitar Pedal

$199 at Amazon, Target and Guitar Center

The NUX Amp Academy offers an impressively broad range of models, with 12 easily accessible amps (six can be active on the pedal at any one time, and you can toggle between the two sets of options in the companion software) from vintage Fender to modern high-gain amps like the Mesa Dual Rectifier series. Along with a switchable boost and three recallable scenes, there isn’t much out there that gives you such a broad palette of tones in such a small package at such an affordable price.

And while it isn’t altogether obvious from looking at the physical pedal itself, there’s a lot more under the hood. Using the app (available for desktop, iOS and Android) you can access all sorts of functions — including a super-simple-to-use IR loader; a wide array of reverbs, compression and overdrive pedals; and a configurable effects chain — and save presets in three “scenes” that you can then access during performances on the pedal itself. It’s an impressive setup, especially at this low price.

As for tones, the Amp Academy is very good for the money. Side by side with the higher priced UAFX pedals, Iridium, Opus or IR-200, the NUX doesn’t quite nail the tones and feel as well, and while it might not be our first choice for critical recording, it’s close enough. But the onboard effects, while convenient, aren’t super convincing.?The drives and compressors here won’t replace your treasured pedals or stand in for a more elaborate dedicated multi-effects unit.

NUX is a value brand, and the Amp Academy does demand a few compromises. First and foremost, the documentation is pretty difficult to parse, and the app equally difficult to use. We had a very hard time establishing a stable connection with our MacBook Pro and were lost as to how to execute a firmware update until we found the brand’s video channel, as the process isn’t described in the manual.

Once we got it all figured out, the software was easy enough to use (and the IR-loading process is simple and about the easiest to manage of any of the units we tested). Not only do you get access to a bunch of onboard effects but you can arrange them in any order you like. You can only do this from the app, though, so you’ll have to remember what’s what and where it lives in the chain in your three scenes. You also can’t toggle things on and off from the pedal itself, but the point of the Amp Academy isn’t really to replace a pedalboard, so we see in the inclusion of drives, compressors and such as a bonus.

The Amp Academy would certainly make a solid choice for live use. (At half the price of many of its competitors, it’s half as much to worry about somebody spilling a drink on.) You also get convenient performance tools like an XLR output with ground lift, a noise gate/noise reduction circuit and the ability to disable the pedal’s IR stage with a switch if you want to run into an amplifier’s effects return and into a real cabinet. Plus, the cast aluminum housing seems built for repeated stomping.

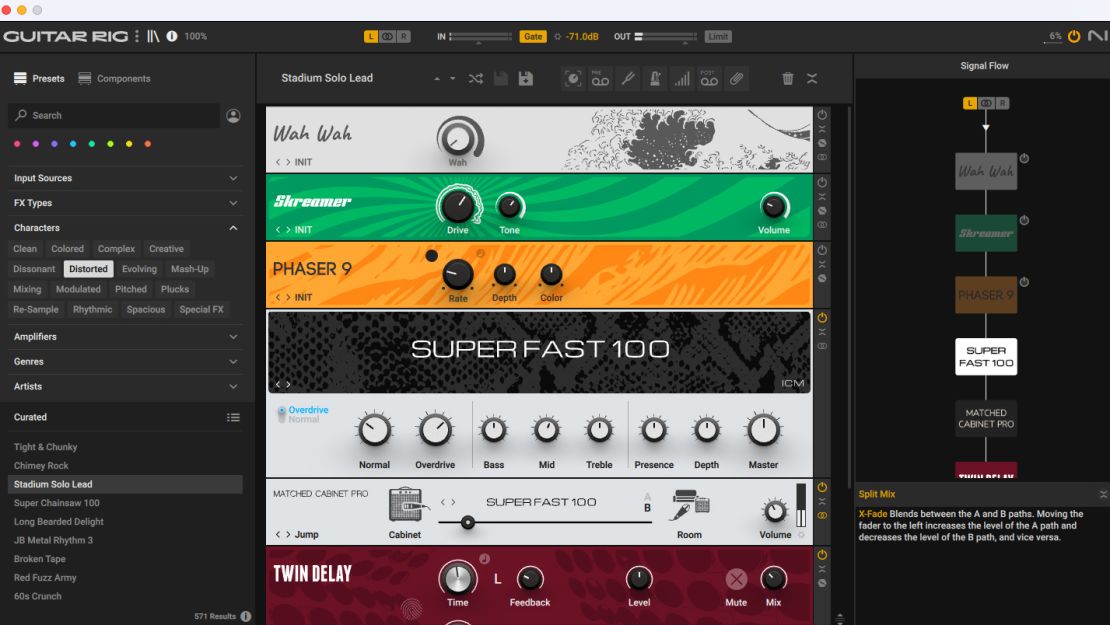

Best amp simulator app: Native Instruments Guitar Rig 7 Pro

$199 $100 at Sweetwater and Guitar Center; $199 $149 at Native Instruments

Given that many amp simulators see most of their time in home or professional studios, you might wonder why you should use a standalone device at all. If you’re happy plugging into an audio interface and listening through computer speakers, you’ll find dozens of apps that fill the need, some of them on par with the best dedicated devices.

The latest version of Guitar Rig, one of the first popular amp simulator software packages (the first version was released in 2004), remains the best bang for your buck and is a great place to start if you’re looking for a wide range of guitar tones from your existing computer. There’s enough here — from basic amps and drives to esoteric effects derived from NI’s board lineup of synthesizers and studio tools — to keep any guitarist or bassist busy indefinitely.

Guitar Rig 7 Pro adds new modeling amplifiers (including significant refreshes of the classic Fender, Vox and Marshall emulators), an improved IR loader and a looper to the already very complete package, including the latest tools at a price competitive with much more focused packages like Neural DSP’s great-sounding but relatively limited app collections.

Most importantly, the Native Instruments software sounds great. The new Guitar Rig held up, by and large, in comparison to the hardware boxes we tested. The UAFX pedals still have an edge on classic tones, and overall the Strymon, Walrus, Amplitube, Two note and Boss pedals feel a bit better to play through. Of course, this may just be a matter of psychological differences in playing through a recognizable piece of guitar gear versus a pedal. We were using an M1 Max machine with a very low latency interface and small buffer setting, giving us roundtrip times under 10 milliseconds, on par with Boss pedals.

It’s simple to get started with Guitar Rig. There are a ton of basic and artist signature presets, and routing is a matter of dragging modules into position in a virtual rack. It’s very flexible as well. Guitar Rig can run as a standalone application or as a plug-in that can run within a digital audio workstation, making it more generally useful than other apps that can only run as plug-ins like Line 6’s Helix Native. Routing within the app is very flexible, though the visual interface paradigm is based on rack-mounted gear rather than pedals, as you’ll find in most apps these days, and the range of effects is as wide as you’ll find anyplace.

Since it sounds great, offers more than any similarly priced software app (and anything comparable is significantly more expensive) and gives you so many options to fine-tune your tone in almost any practice or recording situation, Guitar Rig 7 Pro is ideal for anyone looking to get started playing guitar into the audio hardware you already own.

Other amp simulators we recommend

Best amp simulator for analog enthusiasts: DSM & Humboldt Simplifier MK II

$359 $323 at Amazon; $359 at Sweetwater

The Simplifier MK II is the latest incarnation of Chilean pedal maker DSM & Humboldt’s popular guitar effects pedalboard problem solver, and as with its predecessor, it packs a ton of useful functionality into a tiny, great-sounding package.

While the majority of the devices we looked at for this piece are software based (though they use a wide variety of digital approaches) the Simplifier is 100% analog. It’s in the tradition of earlier devices like the much-loved Tech 21 SansAmp rather than a spin-off of digital recording technology.

You get the requisite Vox, Fender and Marshall tone choices (you can mix and match preamp and power amp types). You can configure things with a three-band EQ (with a ton of usable adjustment — you can really tailor things to taste here) and separate controls for preamp and power amp gain. Further down the chain, these are paired with a stereo cabinet simulator section (you can have different cabinets left and right if you like) that gives you your choice of combo, twin or stack settings per side, along with a pair of “color” controls that tune the overall response and EQ of each cabinet. These replace the “mic position” knobs used on the earlier model of the Simplifier, and do roughly the same job.

Tweaking the cabinet settings and mixing and matching “colors” and cabinet types can produce a very wide stereo image. Paired with a stereo delay or chorus in the effects loop, this can get you some really big atmospheric tones if you’re into that kind of thing. The master section gives you resonance and presence controls to tailor the overall low and high end responses, along with a master volume and a reverb (the only digital component there — a good sounding if somewhat plain large room).

The features here go beyond what most of these boxes provide. There’s a headphone jack with its own level control for quiet rehearsal or auditioning effects, an aux input if you’re learning new tunes or looking to work with backing tracks and an effects loop with a stereo return.

It’s much more tweakable from the front panel than any of the digital amp sims we tried, giving you access to a huge variety of sounds. This is great but daunting. The EQ has a ton of range, as do the drive, presence and resonance and color controls. Slight adjustments can make a big tonal difference, and there’s no way to recall them since there are no presets.

The downsides to the Simplifier MK II are few. One is that it isn’t a shockingly accurate reproduction of any single vintage amplifier. Rather, while it offers Vox-like, Fender-like and Marshall-like flavors, it’s got a character all its own, which resembles other analog “simulators” in this respect. Adding the Simplifier MK II to your setup is more like buying another nice-sounding amplifier; it’s got its own unique characteristics.

More significantly, depending on how you like to use an amplifier, the lack of presets or channel switching means those who are looking to cover radically different sounds during a live set might find themselves needing to bring an extra overdrive pedal. Let’s say you play in a cover band and need to go from an ultra-clean funk tone to a big metal stack, or even from a grainy Vox tone to a twangy Fender sound at the click of a footswitch. You’ll be depending on your other effects pedals to get different tones on the fly.

That said, the Simplifier MK II offers so much flexibility and connectivity in such a tiny package — and sounds so nice — that it’s hard to overlook. If you’re into analog stuff (as many, many guitarists are) this may be the simulation solution for you.

The most versatile amp simulator for your pedalboard: Boss IR-200

$349 at Amazon; $350 at B&H Photo Video

Like the DSM & Humboldt Simplifier MK II, the Boss IR-200 crams a very-good-sounding set of amplifier models and cabinet emulations, plus functionality, into a small package.

Like DSM & Humboldt, Boss doesn’t really offer exact models of popular amps; rather, you get a range of idealized sounds, some of them with the flavor of Vox, Fender, Marshall and various modern, high-gain, metal-oriented amplifiers. It offers a much wider range of emulations than most of the simulators in this price range and configuration and is only rivaled by the ToneX and the Simplifier MK II.

Boss’ digital pedals are known for low latency, and that’s the case here as well. It feels great to play, with no perceptible lag and a real amp-like feel. If you’re picky about this sort of thing, you should definitely check out the IR-200.

On the utility front, Boss also adds a noise gate/noise reducer, equalizers (studio-style graphic and parametric EQs, aside from those in the amp models) and an effects loop. You also get bass amps (it’s unusual to see bass and guitar amp models in a dedicated amp simulator like this), which makes the IR-200 a nice all-in one solution for recording or for instrumentalists who double on guitar and bass. Interestingly, you can set up a separate ambience for headphones, which is nice for practicing with a tone you’d generally use dry (a totally dry cabinet sound is fatiguing to listen to on headphones). There’s even an aux input jack for practicing, a pleasant surprise on a pro-oriented pedal like the IR-200. And you can load impulse response files up to 500 milliseconds long at up to 32-bit, 96kHz resolution.

There are some great interface features here. You can easily disable any element of the emulation — amp, cabinet or reverb/ambience — right from the front panel or bypass the whole unit from the footswitches. This makes it easy to go from, say, direct recording to a computer to a live gig using your amp to some quiet practice without swapping cables on your pedalboard.

Like the bigger GT series Boss units, the IR-200 has a USB interface that gives you the option to record a dry signal to a separate stereo track for later processing or reference or reamping — a really useful figure if you change your mind later. While you will have to install a driver for this, most of the other units we looked at in this price range and configuration didn’t offer any USB recording options at all.

Downsides? For those looking at this as a pedalboard problem solver, the outputs aren’t balanced. So, depending on your situation, you might need a separate DI box to get your signal to a PA system. It’d be great if this had 1/4-inch TRS balanced outputs like the bigger Boss modeling units or XLR outputs like the DSM & Humboldt Simplifier MK II.

The controls are very Boss/Roland, which is to say that you get fine-grained individual control of almost every conceivable parameter, but you’ll have to get into menus to get to what you want. Nothing is global here. If you always want to use the effects loop, you’ll need to enable it patch by patch. Editing takes a bit of menu diving, as we’ve seen in other Boss products.

Nitpicking a little further, while it’s great to have reverbs that are configurable for each preset, there aren’t any amp-style spring reverbs — just studio, room and hall ambiences, which are very well done but do sound a little out of place with the more Fender Twin-flavored amp models. Similarly, there’s no vibrato on the Vox models. You can, of course, add the reverb or vibrato pedal of your choice in the effects loop, so this isn’t too much of a hindrance in practice and the onboard reverbs do sound very good.

Somewhat surprisingly, Boss’ general-purpose, full-service modelers — the GT-1000 and GT-1000 Core — offer more amp models than this dedicated amp in a box. The IR-200 makes up for this with far more impulse response slots and improved file handling for your library of IRs. There’s still plenty of variety here, just not the wide range of emulations you get with the bigger box. The IR-200 is more focused on giving you variations on the basic Fender/Vox/Marshall tones, along with a few nods to high-gain enthusiasts. Those looking for more basic tones will likely be using this with a range of drive and preamp pedals.

Those few omissions aside, few competitors offer such a broad array of features, especially at this price or in such a small, pedalboard-friendly box. For the money, it’s hard to imagine getting more from a dedicated amp simulator with modeling and flexible IR loading for the cabinets of your choice.

The amp simulator for players who want access to every tone: IK Multimedia Amplitube ToneX Pedal

$400 at Amazon and Sweetwater

The ToneX is the first low-cost pedal-format device to offer “profiling,” the machine-learning technology that lets you create playable virtual versions of your favorite physical devices, from preamps and power amps to distortion pedals. The results are very, very convincing — almost spooky — and it sounds incredible.

The ToneX comes loaded with dozens of great-sounding profiles of amplifiers of all types. The profiles can’t capture the response of all the controls of the gear you’re using, so you’re getting a snapshot rather than a movie, so to speak. You also can’t profile time-based or modulation effects, so no vibratos or delays quite yet.

The ToneX absolutely excels at high-gain tones where you’re mostly looking to get accurate or just plain great-sounding gain staging. The profiling process really does the job, and you end up with a chug or riff machine that sounds and feels like playing the real thing, whether that’s a vintage Marshall or a modern boutique amp.

It’s also very versatile in that you can use it not just as an amp simulator but as an overdrive/distortion pedal, capturing select tones of vintage pedals you might not want to take to a gig or lug to a recording session. The caveat here is that, as with amplifier captures, your profiles can’t capture all the behaviors of your favorite devices, just key tones that you’ll be able to tweak with the onboard controls.

We made some captures from a couple of very versatile gain pedals — Walrus’ Eons fuzz and DSM & Humboldt’s Silver Linings — and while the captures really nailed the settings that we used, we found ourselves missing the unique tweakability of those pedals. But this isn’t necessarily a huge issue. If you’re trying to replicate these specific tones night after night on the road or for overdub after overdub, it might even be preferable since all that control means it’s hard to replicate tone precisely.

The downside, exacerbated by the fact that the models can vary so widely and really demand totally different parameters to be exposed for effective control, the physical interface can be a little clumsy to use. The ToneX does have a big, bright LCD-style display, but it doesn’t present full routing information or parameter highlights like the Boss or TwoNotes pedals. The upshot is that you can easily forget (at least we did) which control corresponds to which parameter and which profiles use which parameters to begin with.

Accessing the device via the ToneX software makes things a lot easier, but we’re guessing that the company envisioned the ToneX as a set-and-forget pedal when used live.

You also get access to the huge community of ToneX users, who are very active trading models. If you can’t get access to an amp to profile it or find a commercial IR pack that includes it, you’re pretty likely to run into somebody who’s done it already and is happy to share.

The most flexible recording multitool: Two Notes Opus

$300 at Amazon and Sweetwater

The brand-new Two Notes Opus offers an amazing array of great tones and flexibility in a tiny package. Two Notes has long specialized in tools for recording great amp tones, but the Opus is the company’s most flexible end-to-end solution so far, with preamp and power amp modeling, an impulse response loader for speaker cabinets, plus microphone emulation, reverbs, equalizer and a noise gate with intelligent learn mode. You can even use the Opus as a direct box (with cabinet emulation via the IR loader) for your existing amplifier, though you will need to connect a speaker cabinet or dummy load box to the provided output. (If you don’t, you risk equipment damage or worse.)

First things first, the Opus sounds great, with tons of usable clean, edge-of-breakup and high-gain sounds (the accent is definitely on the harder stuff here). You also get very usable acoustic simulation from the IR module, with body resonances available to give your electric a reasonably convincing acoustic steel string tone in a pinch.

It’s a super-compact and handy package, and it sounds just great. If you’re in pursuit of a full-featured, digital ampless solution without going to a full-featured multi-effects modeler like the Line 6 Helix series, the Opus is very competitive with the Boss IR-200, though it has some significant differences in user interface that may determine which one you end up choosing.

Despite its petite size, the Opus, like the DSM & Humboldt Simplifier, isn’t really a “pedal” per se — it’s simply sized to be pedalboard friendly, but will likely make more sense on a desktop. Side-mounted jacks are easier to get to on a desk, but would mean more space on a board.

The Opus’ companion app, Torpedo Remote (available for Windows, Mac, iOS and Android) is easy to use and really simplifies tweaking, giving you hands on control of everything from basic parameters like gain and EQ setting to microphone placement in a virtual room. You can also upload and manage IRs and Two note “dynIR” modeled cabinets here.

The Opus does have some limitations, and as a new product there are a few things that feel a little unfinished.

Direct control from the mobile app is great, with instant Bluetooth connectivity to our test iPad and from there smooth access to all necessary parameters. IR management, on the other hand, is a little more difficult to figure out; dealing with the onboard microSD card is a clunky two-stage process. You have to enable mounting from the pedal, but you’ll unmount the drive from the desktop. You can drag files onto the? microSD card once it’s mounted on your desktop (great because you can take an unlimited number of IRs along with you wherever you go), but you can only load them into the Opus’ internal memory via the pedal interface, not Torpedo Remote. This seems like a missed opportunity that will hopefully be rectified in a future release.

An effects send and return would have been nice to see as well, opening up the device to 4-cable method use and letting those who like modulation and time-based effects pre-power amp get those sounds.

Maximum IR length is on the short side: 200 milliseconds at up to 24 bit, 96kHz resolution. This may have something to do with the responsive feel, as you can crank the pedal’s roundtrip latency down to 2.2 milliseconds. To do this you need to use much shorter IR files, however. But if you are OK with using even shorter IR files of just 40 milliseconds in length you can use the Opus in this mode. It actually sounds OK; Two Notes does manage to get the best out of those short impulses, so this isn’t a huge cause for concern in practice.

The two-knob menu interface is laid out about as cleanly as I can imagine it being, and the OLED display is bright, readable and well thought out. More onboard controls would have been nicer, even if it made for a larger unit. The Boss IR-200 doesn’t have that much larger a footprint, but it offers much speedier tactile control of key parameters with its nine onboard knobs and dual footswitches.

It would have been good to have some onboard footswitch control too. The full MIDI implementation suggests that Two Notes expects the device to be used by guitarists or engineers who already have a bypass switching system or other centralized MIDI footswitching for their setups, but given how much is under the hood here, a couple of switches would have been nice for utilizing this as a standalone “fly rig.”

Like Boss, Two Notes doesn’t supply amp models that correspond directly to real-world amplifiers. Rather, you get preamps loosely based on Fender (“Foundry”), Vox (“Foxy”) and Marshall (“Albion”) designs, but from there, you roll your own “amp” by combining these with your favorite output power stage, depending on how much headroom and responsiveness you’re looking for. It makes for an impressive selection of tones, but if you’re looking to nail specific tones, you’re likely better served by choosing the appropriate UAFX box.

Whether you prefer the Opus or the IR-200 comes down to use case. The IR-200 makes a better pedalboard manager. With an effects loop and footswitches to step through presets it is very much at home integrated with other pedals. The Opus is more flexible, but without a loop or footswitches (and considering its fantastic app integration) it may make more sense as a studio multitool, letting you capture tones in a variety of situations, whether you use it as a go-anywhere practice tool, dedicate it to an input channel on your mixer or DAW or use it to record your favorite amps.

The best amp simulator for stereo setups: Walrus ACS1

$399 at Amazon or $400 at Sweetwater

The compact Walrus ACS1 is similar in concept to the Strymon Iridium, with models of classic Fender, Vox and Marshall amps, and it is similarly popular. What it offers in a tiny package is true stereo paths. You get left and right inputs and outputs, plus the ability to independently choose amp and cabinet models for each side, giving it a ton of flexibility for stereo rigs and setting it apart from the group.

The models on offer are beautifully rendered. You get a ton of range across the classic tones, and being able to run independent models per side really opens up the stereo field, whether you are looking for a little space or trying for something more dramatic with radically different sounds panned left and right. It invites experimentation, which stereo-dedicated players are likely to really appreciate.

The selection of IR cabinets sound great (a late-2023 update provided an upgraded set of impulses across the board), but if you want to try other alternatives, you can load your own IRs as well. Impulse response files up to 200 milliseconds in length at a resolution of 24 bits, 48kHz are used, though you can upload any IRs you have to Walrus’s web-based IR loader and it’ll automatically convert them for use by the ACS1.

That’s a shorter maximum IR length and half the top end sample rate of the Strymon Iridium, which may account for some of the difference in tone. When auditioning head to head, the Iridium sounds ever so slightly more like an amp in a room. The captures and room ambiences are great, though, and compare favorably with anything else out there.

You can save 128 presets in the ACS1, but you can’t access them without an external MIDI controller. (We used a Morningstar MC8 controller, which was easy enough but did take some configuration. Luckily, both Walrus and Morningstar make easy-to-use apps.)

It’s nice to see full-size MIDI DIN jacks on a compact unit like this; it’s just easier to find the proper cable when you need it.

The best amp simulator for the most accurate vintage tones: UAFX Lion ’68, Dream ’65, Ruby ’63 and Woodrow ’55

$399 at Amazon (Lion)

$399 $300 at Amazon (Dream)

$399 $319 at Amazon (Ruby)

$399 $319 at Amazon (Woodrow)

Universal Audio’s growing lineup of UAFX amp simulator pedals just sound shockingly good.

These things are all business, meant to live on a studio desk or on a pedalboard, standing in with impressive accuracy for a real Vox or Fender amp. The UAFX series features four separate pedals so far: Ruby, which models a Vox AC30; Dream ’65, which covers “Blackface” sixties Fender tones; Woodrow, providing the fuzzy drive of small Tweed Fender amplifiers of the 1950s; and Lion ’68, which covers Marshall high-gain tones from Hendrix through Van Halen. We tested the first three, as Lion wasn’t released until we were completing this review.

It’s neat that you can configure deeper settings on your phone via Bluetooth (and that you do setup and updates within the same UAFX Control app you’d use to manage your desktop plugins), but that all speaks to the professional audience here.

The important thing to know here is that all three pedals we tested sound fantastic. They feel and behave closer to the originals than even the ToneX profiles of these amps. Dream ’65 in particular is astoundingly close, getting you everything from sparkling funk rhythm tones to edgy Texas blues overdrive at the flip of a switch. If you’ve never been convinced by an amp simulator, this is likely the one that will change your mind.

Woodrow and Ruby are similarly impressive. Woodrow has tons of gain of the Neil Young or Billy Gibbons variety, plus it can cover all the vintage flavors you’re looking for if you’re more retro oriented and even clean up for a serviceable hollowbody jazz tone. Ruby nails the Vox tone and feel, whether that’s chiming cleans or Queen-style overdrive. It feels great to play, and the vibrato and brilliant channel emulations are right on the money.

What don’t we like? There are a couple of I/O elements we think many amateur purchasers would like to see here: There’s no facility for recording out over USB and no headphone jack for practice. These are features a professional audience wouldn’t miss, since they’d be using the pedals into a PA, interface or mixing desk. There’s no effects loop either, but that would be out of place for any of the modeled amps here. And there is no auxiliary input (but these things aren’t really meant for practice — they’re tools you buy after you’ve practiced plenty).

The main issue facing a potential purchaser is that you only get one amp type per pedal. The UAFX units sound amazingly realistic and feel incredible to play through, the attention to detail per unit is obvious and having dedicated controls that mirror the options available on the real amplifiers these pedals are based on gives you a degree of intuitive control that’s just superior to anything else out there. But you’ll need to choose your amp as you would when buying the real thing.

We really found ourselves wishing for a 3-in-1 unit like the Iridium or ACS1 that combined the major amplifier types. If you’re looking for versatility, purchasing all three will set you back quite a bit of money, since each UAFX pedal is priced similarly to the Strymon and Walrus units. Unless you are a pro who’s really in need of having access to the specific tones covered by the UAFX units — say, if you’re The Edge and you’re playing a whole lot of nights in Vegas — it might be better to spend that money on a larger, more full-featured modeler or on software products.

But then again, some people collect dozens?of even more expensive amplifiers or, like most guitarists of the last decades, they settle on one that they really like. And if you already know that you’re into the Vox, Blackface Fender or Tweed Fender tone but you want digital convenience for whatever reason — recording, touring, silent playing at home — pick up the appropriate UAFX unit and you’re almost certain to get the sounds you’re looking for.

What is an amp simulator and who is it for?

Amp simulators — which can reproduce the sound and feel of a guitar amplifier without the bother of setting up speaker cabinets or microphones for direct recording or headphone listening — transformed music recording when they appeared in the late 1990s.

With the introduction of industry innovator Line 6’s Helix devices and the rise of competing full-featured amplifier and effects modeling units by Fractal, Boss/Roland, Headrush and others, pro-level modelers can replace not just an amplifier but a pedalboard and rack full of outboard effects gear. With something like the Line 6 Helix Floor or Boss GT-1000, touring or recording guitarists can set up their tones, save them as presets as synthesizer players had long been able to and plug right into a PA system at a gig or mixer at a session and be able to get dependable, repeatable sounds anywhere.

While those boxes are overkill for most home players, a new crop of pedals has emerged, aimed more at replacing just a guitar amplifier, though with the same fidelity as the pro models. These have slowly been winning over even the most notoriously gear-conservative guitar and bass players as more affordable and far-better-sounding devices have become available.

The devices we’re looking at in this review largely follow in the footsteps of the SansAmp, which was introduced by Tech21 in 1989 as the first pedal-format box that simulated an amplifier’s response for direct recording. Since then, new technologies like machine learning-based “profiling” have filtered down to more affordable pedals, and the devices have become popular with everyone from touring professionals looking to save on weight and fuss to beginners looking to learn without disturbing family or roommates.

How does an amplifier simulator work?

There are many paths to simulating the sound and response of an amplifier (or any circuit, really). As YouTuber Jim Lill found out when he tried to figure out exactly what made up guitar amplifier tone, in this case it comes down mostly to gain and equalization. It’s not about magical cloth-covered wire or tubes or how much time a piece of gear has spent aging neglected in a barn loft or bar basement.

You’ll find four main approaches used in today’s amp simulators (sometimes more than one in the same box).

Modeling

Modeling is an approach that involves building a software duplicate of the circuitry used in an amplifier or effects unit, and building it so it duplicates the behavior of that circuitry. While early attempts at this process fell pretty short of the mark, the models used in the devices we looked at — the Iridium, ACS1, IR-200, Opus and UAFX pedals, for instance — can be very, very impressive and, in some cases, indistinguishable from the real thing in the context of a recording or live performance. Often modeled amps are paired with impulse response-based simulations of cabinets and reverbs for an even more realistic overall sound.

Impulse Response

Impulse responses (IRs) are short recordings (generally 2 to 400 milliseconds) made by playing a test audio signal — sometimes a short transient burst, but typically a sine wave swept across the audible frequency spectrum — through a piece of equipment or into a real space. (The recording process resembles the room-tuning routines you may have used to set up your home theater system). That file is read by a piece of software known as an IR loader (or a dedicated piece of hardware running such software) that uses a process known as convolution to decode the IR.?By comparing the recorded signal against the known characteristics of the original impulse file, you end up with a software tool that reproduces the EQ and delay characteristics of the sampled piece of equipment or room. IRs can have a dramatic effect on the realism of a modeled amplifier, so you’ll find dozens of choices onboard today’s amp simulators, and many audio and musical instrument software companies sell packs of IRs simulating various rooms, devices and especially speaker cabinets.

Profiling

Used most notably in the ToneX pedal and software, profiling is the next step beyond IRs. Instead of modeling circuits in software or running audio through impulse response files, the process begins with a recording — or a “capture” — that is then used to train a machine learning routine that figures out how to create usable iterations on that initial sound. This resulting “profile” lets you use the captured device much as you would the real thing. You can profile any element of your guitar rig you like, from a favorite distortion pedal, amplifier, preamp, speaker cabinet or a signal chain, incorporating any or all of those, assuming you have enough computer horsepower on tap. As with modelers, you’ll often find profiled amplifiers and effects combined with IR cabinet simulators, though profiles can also capture everything from preamp to cabinet.

Analog simulation

The original amp simulators didn’t use digital approaches at all. Rather, the Tech21 SansAmp and its descendants such as the DSM & Humboldt Simplifier, use a combination of analog tone-shaping processes — namely equalization and gain staging — to simulate the tone and response of guitar amplifiers.

These types of devices can capture a surprising amount of the flavor of the simulated amps (differences in EQ and gain structure are the key differences between amplifiers), and an advantage of analog simulation is that since there is no digital encoding or decoding, there is no perceptible latency. Some musicians are very sensitive to the minute lag time it takes to get a signal in and out of a computer and piece of software.

How we tested

After calling in a representative pile of amp simulators, we got to work using them in our home studio to compare typical tones.

We ran through all the stock presets on each device and checked out both modern ultra-high-gain and vintage-style rigs in each case, as well as esoteric and experimental amp types where available, but these were secondary considerations assuming most players still get the most mileage from the basic trio designs from the 1950s and 1960s.

For comparison’s sake, we concentrated on the basic Fender/Vox/Marshall tones for evaluation. These remain the most popular amplifier types, they form the core of the models used in the majority of devices we looked at and most modern amplifiers are still variations on these circuits.

We compared by playing back sampled guitar tracks from a looping device (this kept things consistent and saved us from having to play identical phrases countless dozens of times) through each device or app into a Logic Pro session. We also examined representative high-gain or vintage tones from devices that covered a broader range of sounds.

Other amp simulators we tested

Tech 21 SansAmp GT2

$229 at Amazon

Similar to the Simplifier in concept, Tech?21’s original SansAmp was among the earliest solid-state tube amplifier simulator tools, and variants of that box have been heard on countless recording sessions. The GT2, the successor to the original SansAmp, replaces the original’s DIP configuration with a trio of switches that lets you emulate the flavors of Fender, Marshall and Mesa Boogie amps and cabinets.

The SansAmp GT2 is a great tool (we’ve used one for years). Its simplicity makes it very user friendly, and it’s more affordable than most of the units we tested for this story. That said, the Simplifier offers a lot more functionality (effects loop, stereo capability, a headphone amp, reverb and more) and variety of tones that would otherwise cost you extra, so we suspect most people looking for an analog solution will find the DSM & Humboldt unit more satisfying.

TC Electronic Ampworx (DC30, Jims 45 or Jims 800)

$149 at Sweetwater (DC30)

$149 at Sweetwater (Jims 45)

$149 at Sweetwater (Jims 800)

As Universal Audio has done, TC’s new lineup of amplifier simulators offers a single-amp model per pedal. We checked out the DC30, which models a Vox, giving us relatively direct grounds for?comparison with the other devices in our testing pool.

The Ampworx pedals use a common physical layout, though colorway and knob style mirror versions of the simulated amplifiers. You don’t get a bunch of mode switches to access multiple variations on the basic amp flavor, nor do you get room tone or other effects on amps that didn’t offer them in the first place. You do get a choice of cabinet-simulated and direct outs (in case you’re only looking to use the Ampworx as a preamp or gain pedal) and a dedicated 1/8-inch headphone jack for testing tones or quiet practice (handy, and the sole thing we found lacking in the UAFX units).

The emulation here is even more specific than UAFX’s versions, with only a single-cabinet model and preamplifier voicing available. With these, you get what you get, and that is, refreshingly, a good-sounding and pretty convincing simulation of the intended amplifier.

In the case of our DC30 test, we instantly got the Vox sparkle and chime, and with a little gain via the “Boost” footswitch, we got pretty good approximations of the Beatles, Peter Buck and Brian May tones Vox enthusiasts love. Like the UAFX Ruby, you get a dedicated “Cut” control, though you don’t get the amp tremolo or any sort of room emulation. This is a much more basic pedal, better suited to a live pedalboard than clinical recording purposes.

And the Ampworx is a solid choice for a gigging player’s pedalboard. If you’re interested in Vox or Marshall tones (or Fender, now that Ampworx offers a pedal in that tone family as well) for live use and don’t need all the options and software control, you’ll get most of what you’re looking for here — certainly enough to convince an audience — at a third of the price of the UAFX stuff, meaning less worry and fuss. However, for another $50 you can get close to the entire collection and get more flexibility with the NUX Amp Academy, so the choice depends on your needs and budget.

Headrush MX5

$382 at Amazon

The Headrush MX5 is a bit different from most of the other hardware units we checked out for this piece. It’s a full-featured modeling unit that aims to cover an entire pedalboard, and it’s the only big-brand unit that does so at the price of most amp/IR cabinet-only units.

The supplied presets sound similar across the board and largely go for middle-of-the-road mainstream rock tones, mostly tailored to cut through a mix (I’d assume using one of the company’s powered full-range cabinets) and not especially impressive sounding on their own. Cleans are a bit bland out of the box, while gainier tones are tilted toward high-end fizz.

However, since the focus of this article is to look at tools for the home player, it took a bit more tweaking than it did with the other units to get things sounding lively on their own on the MX5. I found more satisfying tones playing around with the onboard collection of IRs and by uploading some third-party files.

The MX5 is absolutely worth considering if you’re looking for a flexible unit that can cover a full range of effects pedal, amplifier and cabinet simulations, but keep in mind that the presets aren’t on the level of what ships with the Boss or Line 6?multi-effects products and don’t sound as good out of the box as any of the dedicated amp simulators we tried.

Neural DSP Archetype: Rabea

$150 at Neural DSP

Neural DSP makes a huge range of software plugins, most of which are collections of three amps bolstered with effects and meant to give you access to the signature tones of prominent modern guitarists. We checked out Archetype: Rabea, the package built around the sounds of versatile UK session player and gear influencer Rabea Massaad and, according to the company, the most versatile of the collections they offer.

As with many of the pedal- and software-based packages we checked out, the Archetype packages don’t specifically emulate vintage amps, but the clean offerings get you close to classic Fender sounds while the dirty tones are closer to contemporary takes on modded high-gain Marshall flavors, somewhat along the lines of Victory’s Kraken amps. These sound excellent, though the preset tones definitely tend toward the needs of the modern metal player. If you want those sparkling, ambient crystal-clear cleans and chuggy drives, you’ve got them at the touch of a virtual button. The controls give you a lot of adjustment, however, so you can get vintage sounds if you so desire, especially from the clean and rhythm amp models.

You get a basic but great-sounding set of effects pedals to go along with that, including drives, octave and a very full-featured delay, plus the app’s secret weapon: a synth plugin that tracks flawlessly and gives you access to a huge range of cool sci-fi sounds, from funky filter squawks to full-on Moogish lead lines if you want to indulge your inner Pat Metheny or Robert Fripp (or ’70s fantasy metal tones, for that matter).

Archetype: Rabea is a great package, and if you’re looking for something that can cover a lot of hi-fi guitar tones or like laying down synth lines from your guitar. If you consider yourself a modern player and you’re looking for great tones for recording, it’s a no-brainer. That said, if you are looking to cover a wider range and you’re looking to get started with direct, computer-based simulation, we think NI Guitar Rig 7 Pro gives you more for your money and can cover a lot of the same ground.

Line 6 Helix Native

$400 at Line 6

Line 6 is probably the biggest brand in amp modeling, having pioneered the digital approach with the original Pod in 1998. Since then, they’ve dominated professional stages with the Helix line of modeling pedalboards. Right now the brand doesn’t offer an inexpensive standalone amp modeler and the cheapest all-in-one units the company offers are a bit outside the scope of this review, but the full version of the Helix Native software gives you everything the company has to offer — and that is a lot —?in the context of a plug-in for your DAW.

The important thing about Helix is that the models sound great: Amplifiers are very convincing (perhaps not quite on par with the latest ToneX profiles, and they don’t have the quick, realistic responsiveness of the Boss IR-200) and offer a ton of deep tweakability. You’ve heard these amps on countless professional recordings, and in the context of a mix, they sound just that — totally professional.

Effects are similarly convincing, especially on the modulation, delay and reverb end of things. Overdrives and distortions are very, very usable if not quite as realistic as ToneX profiles, but as with the amps, while you might notice listening to them isolated while practicing, you won’t have any issues with how they sound alongside other instruments.

The Helix platform has been around for a decade, and Line 6 has continually added new features in updates: more amps, effects and cabinets as well as general performance and efficiency updates, all free so far, so the long-term value of the platform is difficult to beat. Guitar Rig’s major updates have typically been paid, and while the upgrades have generally been worthwhile, it’s an added cost of ownership to keep track of over time.

Really, the only downside here (aside from the fact that there’s only a plug-in version of the software and no standalone, which is more of a convenience issue) is the price. At $2 to $300 more than Guitar Rig, it’s a bigger investment. That said, you get a significant discount if you also own a Helix hardware device — the price comes down to $100 or even less during seasonal sales — in which case we would absolutely recommend Helix Native for desktop use.