A toxic mix of surging rental rates and vanishing support for renters has catapulted evictions above pre-pandemic levels in some major cities.

Evictions have increased most significantly in Sun Belt cities where housing affordability has worsened and where renters often have fewer protections.

Tenant eviction filings are well above the pre-Covid average in Gainesville, Florida (+46%); Las Vegas (+43%); Houston (+42%); Phoenix (+35%); Nashville, Tennessee (+31%); and Fort Worth, Texas (+25%), according to records tracked by the Eviction Lab at Princeton University.

Other cities, including Minneapolis (+44%) and Columbus, Ohio (+37%), are also experiencing higher levels of evictions than before the pandemic.

Three-quarters of the 34 cities tracked by the Eviction Lab saw evictions increase between 2022 and 2023. More than half are above pre-pandemic levels.

The vast majority of evictions are for issues related to nonpayment of rent, according to the Eviction Lab.

Experts blame a combination of higher rent, the expiration of Covid-era protections and policies that make it easier for landlords to evict tenants in some cities and states.

“There has been a real erosion of housing affordability — especially at the low end. Affordable housing has really disappeared,” said Chris Salviati, senior housing economist at rental platform Apartment List.

‘Shame and panic’

Although rent hikes have eased recently, rent is still 21% more expensive nationally since March 2020, according to Apartment List.

Some cities with elevated eviction filings have seen even bigger rent hikes, including Nashville (+22%), Phoenix (+25%), Columbus (+27%) and Las Vegas (+29%).

Kristolyn Lloyd, an award-winning actress in New York City, fell behind on rent when her roommate left during Covid and she was stuck paying for her two-bedroom Manhattan apartment on her own.

“There just wasn’t a lot of incentive to finding a random person to live with when you’re a Black woman in the middle of the pandemic,” Lloyd, who has appeared in shows on and off Broadway, told CNN in a phone interview.

Eventually, Lloyd’s landlord gave her 10 to 15 days to come up with the $15,000 in rent she owed — or face eviction.

“It felt like a failure. It was humiliating, even though no one was around to see the eviction papers,” she said. “I had these feelings of shame and panic. You look around your apartment of 10 years and the things you’ve accumulated and think: Where am I gonna go?”

Desperate to avoid eviction, Lloyd turned to friends and the acting community by pleading for help on GoFundMe. The response was enormous. Lloyd quickly raised more than she needed — totaling about $50,000, including direct payments on Venmo and Zelle.

“It was awesome. A lot of people in my community said, ‘You do nothing but work. If you’re not able to afford rent, that speaks to a bigger problem,’” Lloyd said.

Why evictions are rising

Lloyd is hardly alone.

More than half of all renters are cost burdened, paying more than 30% of their income toward rent, according to the National Low Income Housing Coalition.

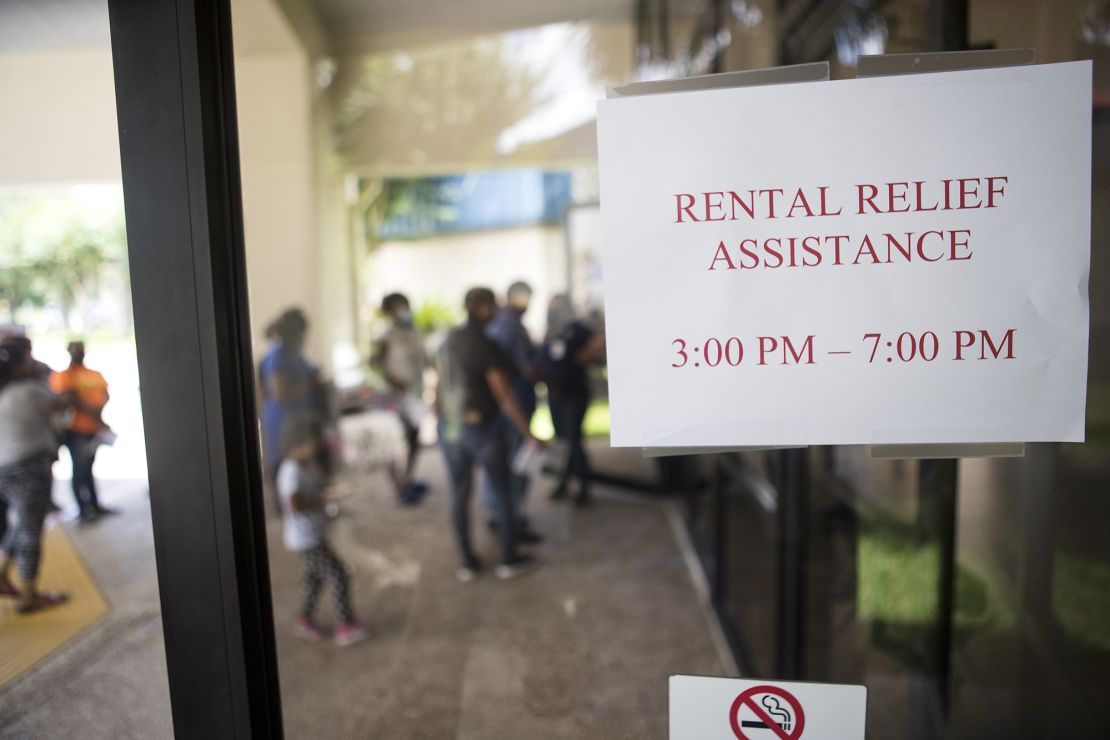

During the pandemic, the federal government provided nearly $50 billion in emergency rental assistance and instituted a national moratorium on evictions for nonpayment of rent.

Those protections helped to slash evictions by more than half in many metro areas, according to an analysis by Princeton’s Eviction Lab.

But that support has lapsed, and many Americans are struggling to make ends meet after years of high inflation.

Diane Yentel, president and CEO of the National Low Income Housing Coalition, blamed the increase in evictions on a lack of sustained renter protections for tenants.

For instance, Yentel pointed to “harmful” bills passed in states including Texas and Florida that prevent tenant protections and the lack of rent stabilization protections in cities including Atlanta, Houston, Las Vegas and Phoenix.

Jacob Haas, senior research specialist at the Eviction Lab, said it’s surprisingly easy and cheap for a landlord to file for eviction in South Carolina, Florida and other states.

“Eviction cases are not like normal court cases. They can often last just a minute or two. A lot of time people won’t even show up to fight it,” said Haas.

“That combination of state, local and federal protections drying up together with rental increases has made it hard for families,” he said.

‘We could end up homeless’

By contrast, cities including New York City, Philadelphia and Wilmington, Delaware, have experienced drops in eviction rates as they have enacted new policies and protections for renters.

For instance, Yentel pointed to Philadelphia, where annual eviction filings are just 59% of their pre-pandemic level. That city has required landlords to participate in a diversion program before attempting to evict tenants for nonpayment of rent.

Another potential contributing factor to rising evictions is the fact that rental properties are increasingly owned by investors.

According to Redfin, investors bought about 19% of US homes in the first quarter of 2024 — the highest percentage in nearly two years. Investors bought around a quarter of the homes sold in markets like Miami, Cleveland and San Diego.

Heather Vargas said she’s been living for months in a hotel with her mother, her husband and their 16-year-old son after her landlord threatened to evict the family from their Citrus Heights, California, home earlier this year.

“I told him we could end up homeless on the streets,” she told CNN in a phone interview.

Vargas, who sometimes cleans homes and whose husband is a truck driver, said she was only late on rent a few times but that her landlord wanted to sharply raise the below-market rent. The couple has struggled to find housing in safe neighborhoods that is within their budget.

“Every time I look at the rent, it just goes up, up and up,” Vargas said. “It’s insane. I never thought we would be here.”