The bodybuilder is causing a stir in Place Vend?me. Prada-clad pedestrians are loitering outside Gagosian’s Paris showroom on rue de Castiglione, peering through its window, perplexed by the presence of a muscular man taking a breather on a bench, a damp towel dangling from his lap. He looks as if he’s pondering his performance on the barbell. Outside, passers-by try to work out if this is a sweaty performance piece.

It isn’t. Duane Hanson’s unnervingly lifelike “Bodybuilder?(1989–90)” — a hollow polychrome bronze?sculpture of a shirtless iron-pumper — is the Gagosian gallery’s showstopper at “The Art of the Olympics,” a two-part exhibition curated in association the Olympic Museum in Lausanne to celebrate the upcoming Paris Olympic and Paralympic Games. If featuring in Instagram posts was an Olympic sport, Hanson’s hunk would win gold.

The gallery is selling 10 sports-related works?by artists, ranging from 20th-century masters Andy Warhol and Man Ray to contemporary figures such Andreas Gursky and Takashi Murakami. Meanwhile, across town in its rue de Ponthieu gallery, a selection of posters from the museum’s collection, created for both summer and winter games over the past half a century, show how art has promoted sporting excellence.

For Gagosian, the exercise is both commercial (prices for pieces range from $60,000 to over $2m) and part of a broader engagement with Parisian life. In 2019, it staged an exhibition in aid of the reconstruction of Notre-Dame. And part of the sale proceeds will go to the Olympic Refuge Foundation, which supports displaced young people through sport.

The works in the exhibition?explore — either realistically or conceptually — sports such as surfing, golf, shooting, running, football and boxing, and include paintings, drawings, sculptures and photography. Pieces range from the monumental — such as Gursky’s huge photograph of a soccer match between France and the Netherlands?— to the whimsical (Mark Newson’s aluminium surfboard is a quirky statement piece).

Art and sport fans are kindred spirits

The parallels between art and sport are myriad, says Elsa Favreau, deputy director at Gagosian when we meet at the exhibition. “There’s a lot of money, there’s a lot of competition. But I think there’s also a lot of excellence.” Similarly, art lovers and sports enthusiasts are kindred spirits: the cheering crowds in the stands are like bidders at auctions, while collectors support artists like football fans worship players. So, is there a dream artist-sport line-up? “’Gymnastics’ by Degas maybe or Giacometti,” suggests Favreau.

One of the show’s highlights — Warhol’s “Winter Olympics,” a sketch of a skier as framed in a photographic negative — gets to the heart of sport as entertainment. The artist, who created a whole series of silkscreen paintings of sportsmen and women such as Muhammad Ali, tennis player Chris Evert and Pelé, observed that “athletes are the new movie stars.” Favreau agrees: “We have great artists here like Takeshi Murakami, who are so well known they are like (French soccer star) Kylian Mbappe.”

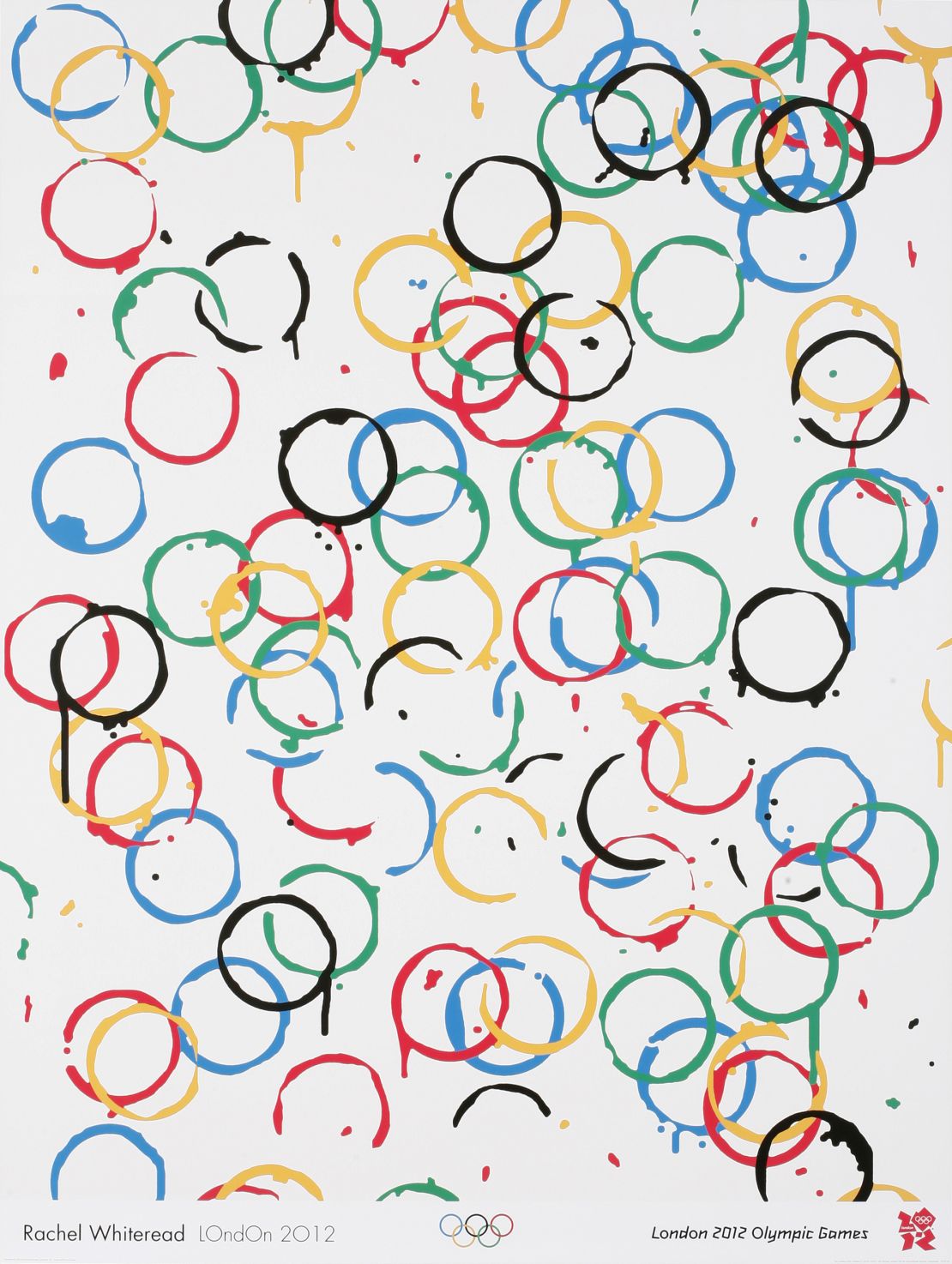

More stars are on view at rue de Ponthieu, where visitors can see poster art by international artists including David Hockney, Pablo Picasso, Roy Lichtenstein and Tracey Emin. An organising committee for each Olympics is responsible for commissioning artists to interpret that particular landmark moment. The Games represented at Gagosian include Munich (1972), Los Angeles (1984), Seoul (1988) and London (2012).

The results are varied and joyous: Hockney created photo-collages of swimmers and figure skaters, Lichtenstein fragmented a horse and rider in motion, Warhol screen-printed a speed-skater, and Howard Hodgkin and Pierre Soulages both riffed on the ripples of the swimming pool. While Picasso’s “The Dance of Youth” — a composition of camaraderie and peace — was repurposed for a poster to mark the opening ceremony at the Los Angeles games, more than a decade after the painter’s death.

Artistic and Olympic feats have been bound together since the dawn of the modern games in the late 19th century. “It’s central to us,” explains Yasmin Meichtry, associate director at the Olympic Foundation for Culture and Heritage, as she shows me the works. Pierre de Coubertin, the founder of the International Olympic Committee, was influenced by the culture of ancient Greece, in which sport was an art. Conversely, Meichtry notes, “there were art competitions as part of the Olympics until 1942.” One wonders how you referee watercolourists.

As well as artistic trends, the posters illustrate changing fashions in typography and design. And then there are the, frequently derided, Olympic logos: London’s zany squiggle triggered epileptic fits when it was animated, while Paris 2024 has whipped up an emblem that looks like a frothy curlicue on a cappuccino. The posters for the Paris games — which are not at Gagosian — have been commissioned from both French and international artists and highlight a move towards emerging and women artists.

Olympians themselves are often artistically-inclined, notes Meichtry. “There’s definitely a strong link between Olympism and a lot of other disciplines.” Again, it is about striving for distinction. There are Olympians who have become artists, musicians, chefs and fashion designers. And the Olympic Museum is drawing together those threads. It hopes to appoint an artist in residence at Lausanne in the near future and, ahead of this summer’s event, has commissioned four athletes to engage with cultural activities.

“We had a very nice experience in Paris with Luc Abalo, the French multi-medallist in handball. He is now a professional painter and we invited him to do a residency at a youth rehabilitation centre in the 13th Arrondissement,” says Meichtry. “He was there for a week with these kids, bringing his experience as an Olympian but also as an artist.”

As with the games themselves, the poster art has evolved over time. “When you look at past editions like Munich or Mexico there was more freedom,” observes Meichtry. “Today there are different rules: how you use the rings and commercial aspects.” But the guiding message remains the same: “That Olympism is a way of life.”

The Art of the Olympics: In Association with Olympic Museum, Gagosian Paris, until September 7, 2024.