Panama, the Central American nation at the crossroads of international trade and migration, will elect a new president on Sunday after a campaign season mired in legal uncertainty.

“It’s a very important election, the most important since after the US invasion” in 1989, said Daniel Zovatto, a global fellow with the Latin America Program at the Wilson Center, a think tank.

“The situation is very complex and the next president, whoever is elected, is going to have an agenda overloaded with problems in a country that is very polarized and undergoing a lot of political tension and uncertainty,” he added.

At stake is the financial stewardship of a country of 4.4 million people, which is facing high inflation and a stagnating economy that has led to widespread unease. Water access will also factor high into voter’s minds, analysts say: droughts exacerbated by El Nino have made access to potable water scarce in some regions and reduced the capacity of the Panama Canal, a centerpiece of the country’s GDP.

Once a GDP leader in the region, Panama’s economy has slowed dramatically in recent years, with the IMF forecasting GDP growth of only 2.5 percent this year, down from 7.3 percent last year. In March, credit agency Fitch downgraded Panama’s rating to junk status citing “fiscal and governance challenges” that followed a controversial decision to close the country’s largest mine last year.

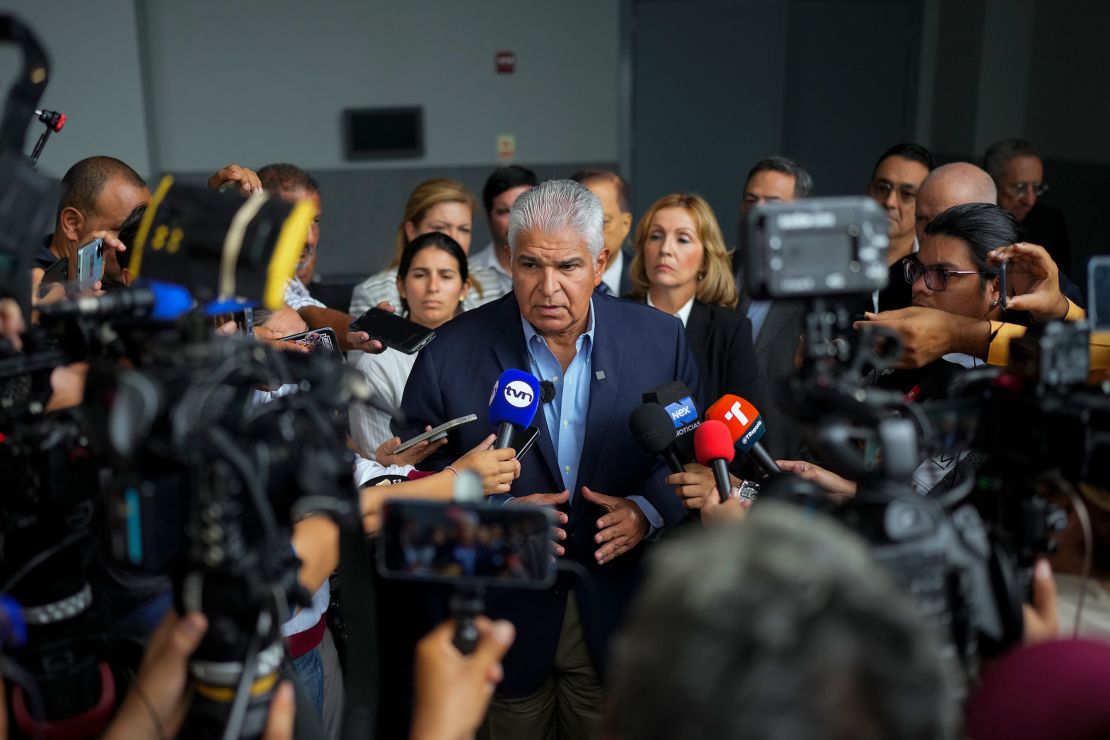

Among the favorites, José Raúl Mulino, a rightwing former public security minister, has pledged to return the country to its economic heyday and to tackle high unemployment with a plan to incentivize private hiring with government funds.

More controversially, Mulino has also vowed to shut down the Darién Gap, the treacherous stretch of jungle beginning in Panama that’s become a main highway for migrants making their way to the US – a phenomenon that is fueling political chaos in the United States as Americans prepare for their own presidential vote this fall.

More than half a million migrants, mostly from Venezuela, crossed through the Darién Gap in 2023, according to the Panamanian government, twice the amount recorded in 2022. The US has been working for months with officials in Panama and Colombia, where the jungle ends, to attempt to shut down the route.

Mulino has not said how he would carry out a closure of the jungle to migrants, and some analysts “question whether this would stem migration or simply prompt new routes,” an Americas Society/Council of the Americas report said.

Corruption at the top of ballot issues

For Panamanian voters, corruption is top of mind as they head to the polls, according to recent Gallup polling, followed by unemployment, unsatisfactory medical care, and the cost of living.

The case of former President Ricardo Martinelli, who was disqualified from running by the courts because of a past corruption conviction, stands out.

Martinelli was sentenced to more than 10 years in prison last year after being convicted of money laundering in the so-called “New Business” corruption scandal.

The case related to a publishing group that, according to the country’s public ministry, was purchased with funds that came from state contracts that were handled irregularly. Martinelli, who maintains his innocence, is currently taking refuge from local authorities in Nicaragua’s embassy in the Panama City, and Nicaraguan authorities have granted him asylum.

Once the favorite to win this year’s presidential race, Martinelli was disqualified from running by Panama’s electoral court in March because of the conviction and sentence. Mulino, who had been Martinelli’s running mate, then took over the ticket for the Achieving Goals party.

But Mulino’s candidacy was challenged as well and under judicial review until just days before the election, injecting uncertainty into the race. On Friday, the country’s Supreme Court decided that Mulino’s candidacy was constitutional and therefore could proceed.

There are seven other presidential candidates, including current Vice-President José Gabriel Carrizo,?former President Martín Torrijos, and Rómulo Roux, another former minister under Martinelli. There is no presidential runoff in Panama and no minimum threshold to win, so an eventual victor could succeed with far less than majority support from the electorate.

Martinelli has thrown his support behind Mulino, even releasing campaign videos from inside the Nicaraguan embassy.

Mulino in turn is widely seen as having inherited Martinelli’s popular support and mirroring his plans to revive policies from the president, which is “remembered largely for economic growth and poverty reduction, which resonates with voters facing high inflation and unemployment rates,” Americas Quarterly wrote.