Tyler Anbinder didn’t know what he’d find when he started digging?into a vast trove of records?that had been locked inside a bank — and inaccessible to the public —?for nearly 150 years.

One detail immediately caught the historian’s attention: The accounts described in the bank’s ledgers had much more money in them than he expected.

As he first combed through files from the Emigrant Savings Bank at the New York Public Library that day about 25 years ago, Anbinder was working on a book about the city’s famed Five Points neighborhood.

That 19th-century enclave, portrayed as a battleground for warring criminals in the 2002 Martin Scorsese film “Gangs of New York,” was “notoriously overcrowded, run-down (and) impoverished,” Anbinder notes. It was also “home to more Irish immigrants than any other part of New York.”

Still, the bank records Anbinder found revealed that even day laborers, who many would assume lived hand to mouth, had savings in their accounts that would amount to around $6,000 in today’s dollars.

“I was really surprised … It just went against the whole reputation of Five Points that it was this terrible, impoverished place,” he says. “It’s not that they were rich, but they weren’t poor. And their bank accounts clearly showed that most of the people who lived in Five Points could afford to live elsewhere if they wanted to.”

That finding stuck in Anbinder’s mind for years, and eventually became the basis for his latest book, which published last week. In “Plentiful Country: The Great Potato Famine and the Making of Irish New York,” Anbinder uses the bank records to dispel a myth that’s prevailed for generations about the 1.3 million Irish people who fled to the United States when famine hit their homeland.

He argues that many weren’t “immigrants locked in gloomy lives of poverty,” as they were often portrayed — not just in more recent Hollywood movies like “Gangs of New York,” but also by their contemporaries and by generations of scholars.

Anbinder, an emeritus professor of history at George Washington University, paints a distinctly different picture of the famine immigrants. That’s something he says he could only accomplish because the extensive biographical information in the stunningly detailed bank records?allowed him to do something that past historians and even descendants of this group of immigrants couldn’t.

With assistance scouring records from dozens of his students?and a professional genealogist, Anbinder documented more than 1,200 famine immigrants’ lives in detail over time — looking beyond the moment they arrived on US soil and showing what happened to them afterward. Many of them, he says, did better than longstanding stereotypes would lead us to expect.

“All those stories, which were untraceable before, I bring out for the first time in this book,” Anbinder says.

A few days before St. Patrick’s Day, Anbinder spoke with CNN about some of the most fascinating details he unearthed and how the history behind them still resonates today. His comments have been edited for length and clarity.

You note that, for years, there’s been a myth many believed about the Irish immigrants who came to the US during the potato famine — that they were so impoverished they could never make it in America. Why did it perpetuate for so long, and when did you start to suspect that the story was different?

Ever since the famine immigrants arrived, Americans were convinced that they could not succeed in America. In those days, it took a lot of resources to make it to the United States. The journey from Europe was 35 days … You had to bring your own food.?You had to make it to Liverpool, and so you had to have a good amount of money to come to the States. Typical immigrants to the United States were fairly well off.

With the Great Potato Famine, where all of a sudden millions of people are starving in Ireland, people are fleeing and they get on ships even though they don’t have 35 days’ supply of food. And they just figure, somehow, they have to make it, because it’s life or death. They get to America half-starved. And many of them are discriminated against because they’re Catholic. Americans thought, “The Irish, they can’t succeed here. They’re too poor. They’re too Catholic. They don’t have the capital — the resources — that other immigrants had brought with them.”

And then through the generations, historians started making the same argument. In part, that was because it was just impossible to trace Irish famine immigrants and find out what had happened to them. There were just too many with the same names, hundreds and hundreds of Murphys and Kellys and Sullivans.

But when the records of the Emigrant Savings Bank became available at the New York Public Library, I went there and started looking at the bank accounts of people who lived in Five Points.

I had another book planned, but all the while I kept thinking, these bank records are just so insanely good, because they have so much biographical detail about each depositor. You could see what happened to them, because it listed so much detail about their families and where they came from in Ireland when they arrived in the United States. And then over the years, as their occupations changed, as their addresses changed, they would give that information to the bank, and so you could trace them. And then even people who only had bank accounts for a few months could be traced. There was so much biographical detail in the bank records that allowed you to tell one Michael Sullivan from the next. After I started researching the whole of Irish in New York, and not just Five Points, I saw that the upward mobility for the famine Irish was really quite remarkable.

When you came across these records from the bank, did you set out with a hypothesis, or did you just say, let’s see what story comes out when we try to look over time at this group?

I?knew that the Irish had saved more than I expected. But I didn’t know that there was socioeconomic mobility tied to that. My goal was just to use the fact that you could trace these people’s lives like never before to try to tell the story of the famine immigrants with a level of detail that had never been done before. I made myself a little Excel spreadsheet and I put people in it. Each person got a line.

As I went from having 10 lives to 100 lives to 1,000 lives, I came up with codes (for different types of jobs) and tallied it up. What I found in the end was 41% of the people who started out as day laborers and other unskilled positions end up at the end of their lives as business owners or other white-collar jobs.

Nobody — even the experts in Irish American history — nobody imagined that four in 10 day laborers could end up in white-collar jobs. This is just inconceivable to anyone who had ever thought about the famine Irish given the obstacles that faced them.

Why did you feel like this story needed to be told?

There are just so many stories that you uncover. And what they all show is how ambitious and driven the Irish were.

And it tells you so much about immigrants today, because immigrants today are really just like immigrants 175 years ago. Like the famine Irish, they’re not the dregs of the societies they come from. They are the most ambitious people, and they’re people with some resources, typically, to get to the United States. They tend to be very young, very driven.

The native-born Americans at the time the famine Irish came said, “oh, they’re going to all ask for charity and we’re going to have to support them.” But no, they didn’t want to rely on charity. They wanted to make money. They wanted to become rich. And they worked really hard to try to do that.

Today’s immigrants do the same thing. Once our ancestors become hyphenated Americans, we forget. We don’t realize that they went through the same things that other immigrants have gone through.

The publisher’s description of your book notes that four US presidents descended from the famine immigrants. That detail really jumped out at me.

They’re mostly recent. Biden, Obama, Reagan and Kennedy.

Was there anything particular to the Irish famine immigrant experience that somehow kind of set the stage for that?

What I think is more surprising is that there haven’t been more. And the reason there haven’t been more is because of what I was saying before. It’s hard to remember in the 2020s how strong anti-Catholicism has been in American history up until very recently. With Kennedy, that was a huge deal. People thought, how can we elect a Catholic president? He’s going to just do whatever the Pope tells him to do. Kennedy had to go to great lengths to say, “I am not beholden to the Pope and I don’t take my commands from Rome.” Biden doesn’t have to say that, so that’s a way in which things have changed.

When the famine immigrants arrived, how did they encounter this prejudice as they were trying to establish themselves in the United States?

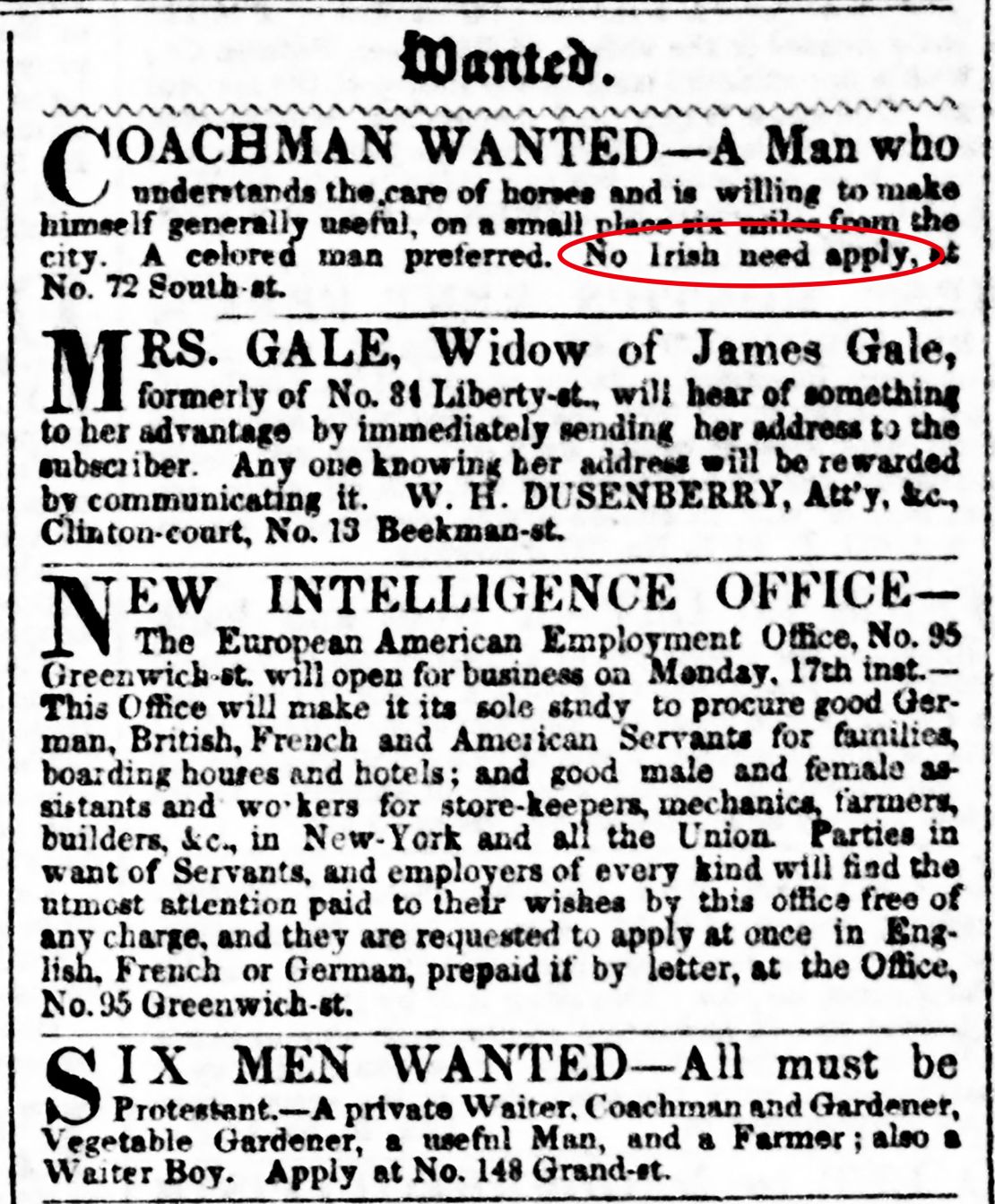

The prejudice took several forms. The Irish were denigrated as lazy, as stupid, as incompetent. Those stereotypes led to another kind of discrimination: employment.

If you had an Irish accent, there were lots of jobs you simply couldn’t have, unless you could find an Irish employer to hire you for that kind of job.

That also manifested itself in advertisements in American newspapers saying, “no Irish need apply.” Those were pretty rare, because most newspapers refused to publish them. When they did publish them, people boycotted their newspapers. But every once in a while, one got in. And even though those were relatively rare, they were so well remembered and so outraged the Irish that it scarred them.

Lacking employment opportunities means it’s harder to climb the socioeconomic ladder because you can’t advance to the higher-paying, white-collar jobs as easily as native-born Americans can. The result, however, is in some ways beneficial to the Irish, because what the Irish then do is they concentrate in terms of their aspirations in self-employment, starting their own small businesses. Because your boss can’t discriminate against you if you’re the boss.

So Irish immigrants are much more likely to start businesses than native-born Americans in that era. Just like today, immigrants are much more likely to start small businesses than native-born Americans. And that’s not a coincidence.

You paint such a vivid, horrifying picture of how devastating the famine was. Why did you feel it was important to delve into that before you got into what life was like for them in the United States?

The famine really scarred these people. And you see that manifested in so many different ways. Probably the thing that I saw the most with the records that are available is the way the famine immigrants were obsessive savers, because they never wanted to be in a position again where they couldn’t buy food for their kids.

I talk towards the end of the book about this one guy who is a gardener for his first 10 years in America. He saves enough money as a gardener to open a saloon in Manhattan, just south of the George Washington Bridge. He opens a saloon up there, which he can afford to do on his gardener savings, because it’s kind of out of the way. But the city grows, and it grows around where he set up the saloon. He runs it for 30 years. And when he dies, they come and evaluate his possessions for probate purposes. And this house has hardly anything in it. And they say $30 worth of possessions is all he has. But he also has this tiny safe. And the judge allows them to open it.

There are bank books from 30 different banks. It turned out he had the equivalent of about $1 million today in 30 different bank accounts and government bonds and real estate, and he owned whole blocks of northern Manhattan as part of his real estate holdings. That was the kind of thing you did when you were scarred so much by the famine.

I thought it was interesting that they were using banks for their savings. Today we hear a lot about the unbanked.

There’s a couple of reasons for that. In your tenement in Five Points, or pretty much any place in New York in those days, there were no locks on the doors. So you either had to carry your money in your pockets or put it in the bank. Tenement apartment robberies were common.

The other thing was, banks paid really high interest rates. Today, you put your money in your checking account, you get 0.1%. The Emigrant Savings Bank paid 6% or 7% interest every year, whether it was good times or bad. That’s huge.

If you’ve come from a place like Ireland where you’ve been so poor — somebody’s willing to pay you 6% or 7% interest, that’s a lot of money that you’re throwing away if you don’t put your money in the bank.

And as a result, what we can tell is that at the very least, half of Irish New Yorkers had bank accounts, and probably a lot more. And studies even show that Irish immigrants, were more likely to have bank accounts than native born Americans.

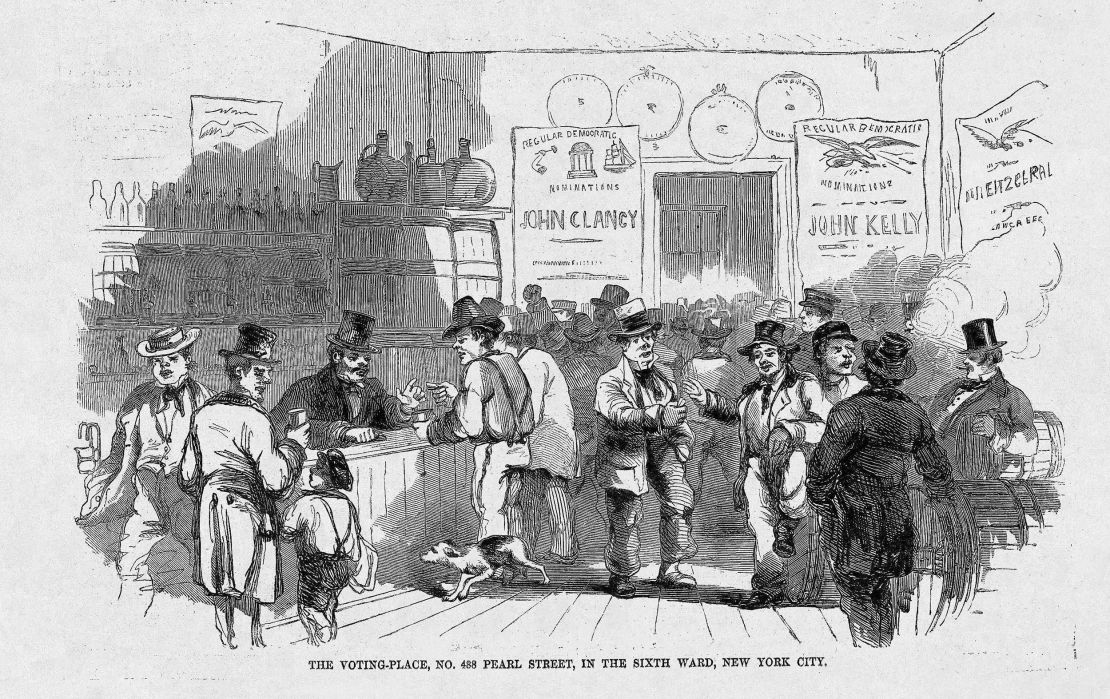

In the book you mention being a police officer or saloonkeeper were paths that a lot of people gravitated towards. Why was that?

There were a couple of reasons that an Irish immigrant would want to be a policeman. First of all, it was a position of respect and respect was something that the Irish had very little experience receiving in Ireland under British rule. Second, it paid well. Third, it paid whether there was rain or shine. The jobs that most Irish immigrants had when they got to America were seasonal. The number one industry that Irish immigrants worked in was construction. And then the final thing was it had a pension, which was just inconceivable to most famine immigrants that they would keep paying you after you stopped working.

Becoming a saloonkeeper was popular because it was considered the pinnacle of Irish American success. The only Irish immigrants who had more money in their bank accounts than saloonkeepers were doctors and lawyers, and very few of the famine immigrants had the education necessary for those jobs. As a result, if you wanted to strike it rich in America, being a saloonkeeper was your best bet.

Zooming out and thinking of the broader American story, how would you describe the significance of the famine immigrants?

The famine immigrants really were the ones who cemented the idea of the American Dream as we understand it today.

Up to that point, people thought only the right immigrants could make it in America. You had to be Protestant. You had to be educated. You had to have some resources behind you. So when the famine Irish get to America, people say, “oh, these people can’t succeed. They have the wrong religion. They’re so uneducated.” More than half of them couldn’t write their own names. But the famine Irish proved that anyone could succeed in America.

And the fact that they climbed the socioeconomic ladder so swiftly — even if it was not something that was recognized immediately in the United States — eventually it was recognized.

That changed the whole idea of the American Dream to Americans. And from that point on, Americans never said only certain people can succeed in America. Americans revised the idea of the American dream to its current iteration, which was the idea that America has the right circumstances. It allows anybody to rise from rags to riches. Anybody can succeed because America is uniquely full of opportunity and economic vibrancy.

As part of your research, you traced some of your own Irish family tree. Were you excited to learn that you had a personal connection with this chapter of history?

I was, because I didn’t know I had a famine immigrant in my family tree. And the immigrant himself, John Killeen, I thought his story was fascinating.

He worked for the New York Central Railroad for 50 years, until he’s 80 years old. That was very typical of the famine immigrants. You have a job, you don’t just give it up voluntarily. You keep working as long as someone is willing to pay you, because who knows what’ll happen.

How important is New York City in the Irish famine immigrant story? How did they shape New York and how did the city shape them?

About 80% of all immigrants arriving in America in those years landed in New York. The Irish overwhelmingly land in New York when they arrive in America, and because they’re so poor, most of them can’t afford to go any farther than New York when they first arrive.

So most of the famine immigrants have an experience in New York. They might not live there for their whole lives, but most of them live there for at least a few months. And certainly a large majority lived there for at least a few years. After five years, probably the majority have moved someplace else.

But New York really shaped them and shaped their perception of the United States. It shaped how they looked at doing business and opening a business. It taught them the value of real estate.

Early on, you might invest your money in a saloon. But saloonkeepers eventually learned that the safest place to put their money was not in more saloons, but in real estate. And often that was in Manhattan. But then sometimes they would say, well, I can buy a 25-by-100-foot lot in Manhattan, but I can buy a whole block of Chicago for that same price when I move there. And then I can rent all those blocks out and become a landlord.

As the famine immigrants spread out across the country, they took those New York experiences with them and helped shape America. Whether it’s California or Minnesota or Saint Louis, wherever they went, they used what they had learned in New York to make their way.