Editor’s Note: In?Snap,?we look at the power of a single photograph, chronicling stories about how both modern and historical images have been made.

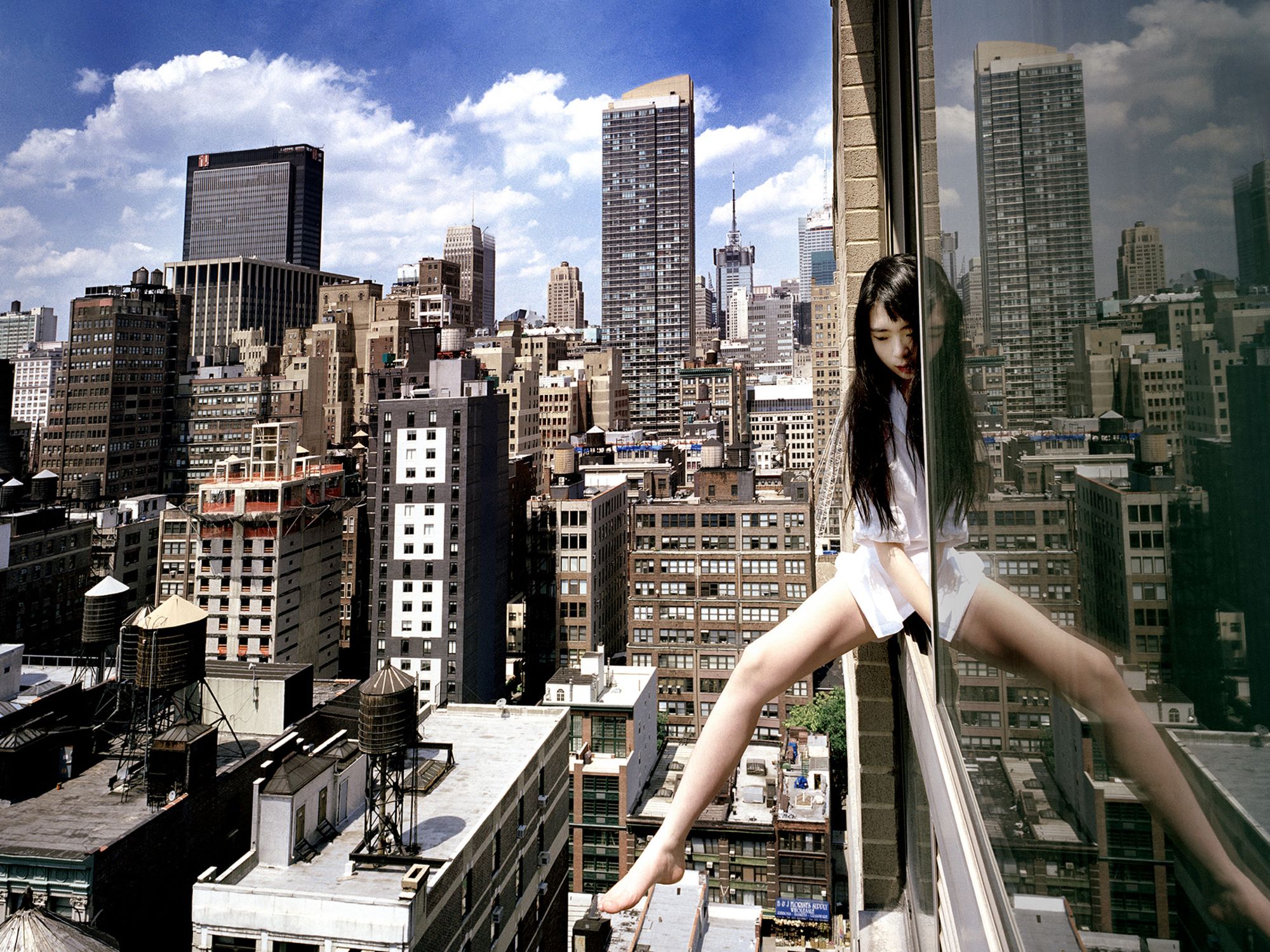

Twenty-four floors up a Manhattan high rise, the photographer Ahn Jun sat on her windowsill one crisp day in 2008, dangling her leg precariously outside over the city.

Fearful of heights, the South Korean photographer was beginning a yearslong body of work that pushed her to her limits, placing herself on top of skyscrapers to shoot vertiginous, stomach-dropping perspectives. In the self-portrait series, Ahn sat on roof corners and building ledges, sometimes showing her whole body perched on the edge; in others, just her legs and feet are visible above the straight vertical drop below.

What brought the photographer to the brink? It wasn’t a sudden interest in thrill-seeking behavior, but a more conceptual idea that Ahn was chasing: the sense of the void. As she dwelled on her adolescence ending, she came to define the present as a void between the past and future, she explained over email. The first time she looked out over her apartment’s edge in Manhattan seemed to her to crystallize that feeling.

“I approached the ledge and looked down, and there was the void,” she recalled.

Previously, rooftops had always brought to Ahn’s mind a sense of ease and comfort. On sunny days, she’d enjoyed the warmth and light winds while working from her rooftop as an English-to-Korean translator, which supplemented her graduate studies at the Pratt Institute in Brooklyn. But as the financial crisis of 2007 cratered the economy, she overheard a stranger at a party joke about his friend, who’d lost a significant amount of money in the stock market, wanting to jump to their death.

She began to think about the rooftop as a dichotomous place. “It’s a place of rest for me, but it can be a place of the last moment of? life for someone in despair,” she said.

Living the high life

For five years, Ahn photographed herself on rooftops — sometimes she wore a mountain climbing harness to keep her steady, but other times nothing at all. Though she sometimes played with perspective, she never used Photoshop to enhance her images, she said. At first, her locations were high atop hers and her friends’ apartment buildings in New York, but over time the project expanded. She secured permission for a shoot at the top of the 63 Building in Seoul, a “symbol of rapid economic development” in Korea, she explained, and she also photographed in Hong Kong with support from its tourism board.

After landing the cover of an issue of the British Journal of Photography in 2013 and receiving online press from outlets like The Guardian, her images went viral.

But that year, Ahn stopped making the series. The way her images were being understood by viewers had drastically shifted with the rise of Instagram in the early 2010s, she said. She had initially thought of her project as a “performance without audience,” but on the nascent social media platform, she explained, the images bled into the “continuous trend of performing our life on camera.” Internet users were also associating her images with the selfie trend of “rooftopping,” she said, where daredevils climb skyscrapers and other tall structures without equipment and pose for selfies at the top.

Soon, she was flooded with emails, Ahn explained, some with positive feedback, but others critical of her work, or sexually harassing her.

She decided to move on to other projects, though some prints have continued to exhibit, most recently at Paris Photo and the Daegu Photography Biennale in South Korea, last fall. In April, she’ll include some of the works in a show at the Irie Taikichi Memorial Museum of Photography in Nara, Japan.

A decade later, the early self-portrait series has proved influential on her later work; Ahn has continued to explore time, space and gravity — after all, she said, she thinks of life “as a process of free fall.” While studying for her PhD at Hongik University in Seoul, from where she graduated in 2017, she became interested in high-speed photography’s ability to snap images that seem to defy physics. In two ensuing photos series, she captures small boulders and apples suspended — perfectly still, and yet inherently in motion — above seascapes and architectural spaces as they fall to the ground.

Since 2021, a small retrospective of Ahn’s work has traveled internationally, titled “On Gravity,” based on the notion of trying to find beauty and meaning in the face of an inevitability, she said. “You can face it and accept, or try to resist,” she said. “For most of us, our life is somewhere in between.”