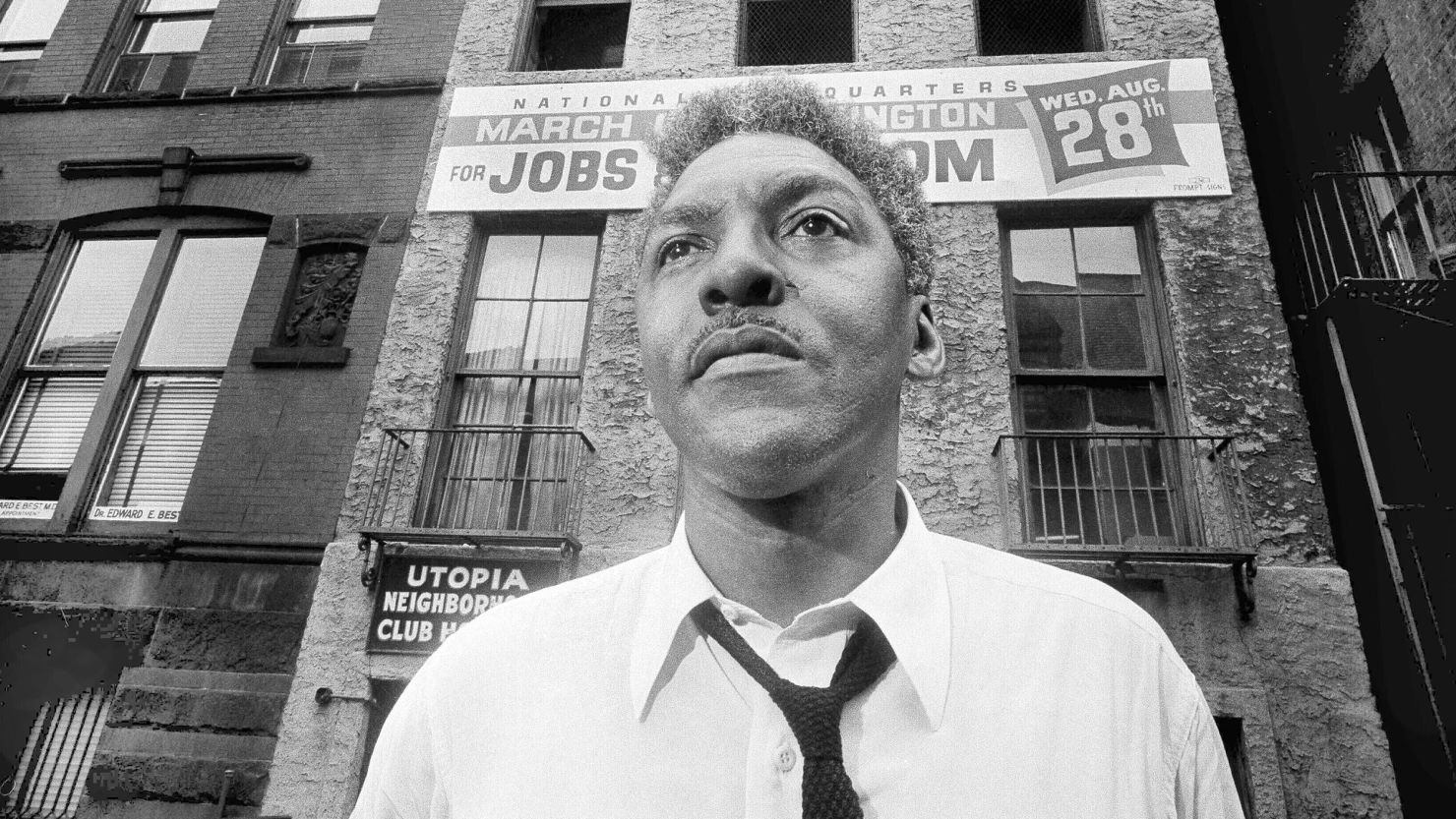

He stood 6-foot-1, weighed 190 pounds and moved with the grace of an athlete. A sharp dresser who favored linen shirts and stylish ties, Bayard Rustin sported a Clark Gable mustache and adopted a British accent that gave him an even more courtly bearing.

There was no civil rights leader who quite looked or spoke like Rustin. He was the Rev. Martin Luther King’s nonviolent spiritual mentor, the chief organizer of the epic 1963 March on Washington and an openly gay Black man who “never apologized for who he was, what he believed or who he desired” during an era when homosexuality was seen as a perversion deserving imprisonment.

“He looked great on a speaker’s platform,” says Arch Puddington, who worked with Rustin in the early 1970s at a labor organization that encouraged Black workers to be more active in unions.

“He’d get up and speak to some of these Black audiences and he could really set them on fire,” Puddington told CNN. “And he hardly ever spoke from a text. I would write text for him, and he would just completely ignore it.”

The man who organized what was then the largest peacetime protest in American history eventually became known as the movement’s “unsung hero,” largely fading into obscurity by his death in 1987.

But now Rustin is returning to the spotlight. ?“Rustin,” a biopic that depicts how Rustin navigated a gantlet of personal and political hurdles to pull off the March on Washington, debuts on Netflix today.

The film, made by?Barack?and?Michelle Obama’s production company, comes amid a mini-Rustin renaissance. Recent months have also brought a new musical, “Bayard Rustin: Inside Ashland,” and a new book, “Bayard Rustin: A Legacy of Protest and Politics,” edited by Michael G. Long.

The new film is a good introduction to Rustin, and how social change takes place. Directed by George C. Wolfe, it crackles with energy. The actor Colman Domingo captures much of Rustin’s charisma and shrewd intelligence. The movie also reveals how some of the biggest battles civil rights leaders fought to put on the march were with one another, over turf and ego.

Much of the film’s urgency is a result of its tight focus. It’s structured around Rustin’s frantic campaign to organize the march, showing how he and 200 volunteers summoned 250,000 demonstrators to Washington with only two months for planning. They did so during an era of clattering typewriters, landline telephones and mimeograph machines — long before the internet or social media existed.

“It was the greatest moment in my life,” Rustin said in an oral history of the civil rights movement called “Voices of Freedom.”

It was one of the greatest moments in American history as well. The film, though, offers something more than a history lesson. It offers at least three lessons on leadership and social change.

Lesson 1: Character counts more than charisma

Character, it’s been said, is who you are when no one is watching. Rustin’s film, and his life, illustrates that lesson in several ways.

The civil rights movement was full of charismatic speakers. Yet many of its greatest leaders defined themselves not by what they said on camera, but by the decisions they made in private.

Malcolm X, for example, could fire up a crowd like few others. But his decision to break with Elijah Muhammad, founder of the Nation of Islam, helped seal his greatness. He knew his decision would likely cost him his life, but he was willing to take that chance because of his integrity.

King’s decision to oppose the Vietnam War was also widely unpopular. He lost the support of an American president, Black leaders turned against him and donations to the civil rights organization he co-founded dried up. But he did so because, like Malcolm, he shared a core commitment to his integrity.

Many pivotal moments in “Rustin,” and in the activist’ life, come down to the same moral calculus.

In a tense, private meeting depicted in the film, A. Philip Randolph (magnificently played by actor Glynn Turman) stands up for Rustin when other civil rights leaders tried to get him booted from the march because of his sexual orientation.

Rustin earned the respect of people like Randolph and King in part because of what he did when the cameras weren’t turned toward him.

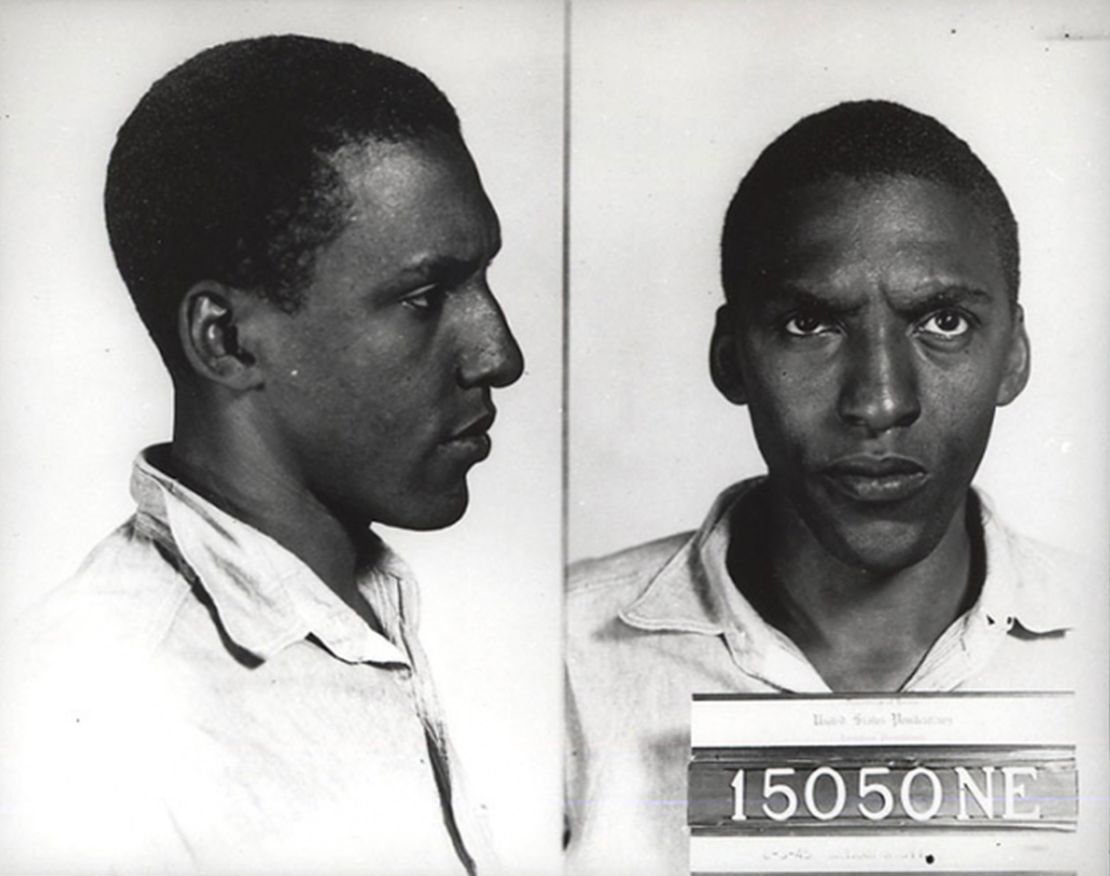

He was a pacifist who went to prison during World War II rather than violate his beliefs. He did time on a chain gang and was viciously beaten several times for his activism but refused to retaliate because of his belief in nonviolence.

He also spent time in India studying Gandhi’s philosophy of nonviolence, which he later passed on to King — leading some to call him the “American Gandhi.”

Rustin was deeply involved in virtually every major civil rights struggle of the mid-20th century, when many of those movements weren’t popular or covered by the press.

“He [Rustin] established a standard for honesty and fortitude that was unusually high in his era and much needed in ours,” Puddington wrote in one essay about Rustin.

Rustin’s character could also be seen in the way he handled his sexual orientation: no apologies; no double life.

During one scene of the film, he tells King he’s not going to hide who he is from other civil rights leaders.

“On the day I was born Black, I was also born a homosexual,” he says. “They either believe in freedom and justice for all or they do not.”

Lesson 2: Every movement needs a ‘glue’ person

General Omar Bradley, an American commander during World War II, is known to have said: “Amateurs talk strategy and professionals talk logistics.”

Bradley’s quote may be apocryphal, but it reflects a truism in warfare. The best-supplied armies often win. Battlefield victories often result not from clever strategies but from logistics — making sure troops have enough supplies and working equipment.

The same principle applies in sports. In the NBA, for example, there are certain unglamorous players on championship teams known as “glue guys.” They do the dirty work of setting screens, delivering hard fouls, rebounding and playing defense.

Rustin was the “glue guy” leader for the civil rights movement. Every movement needs one.

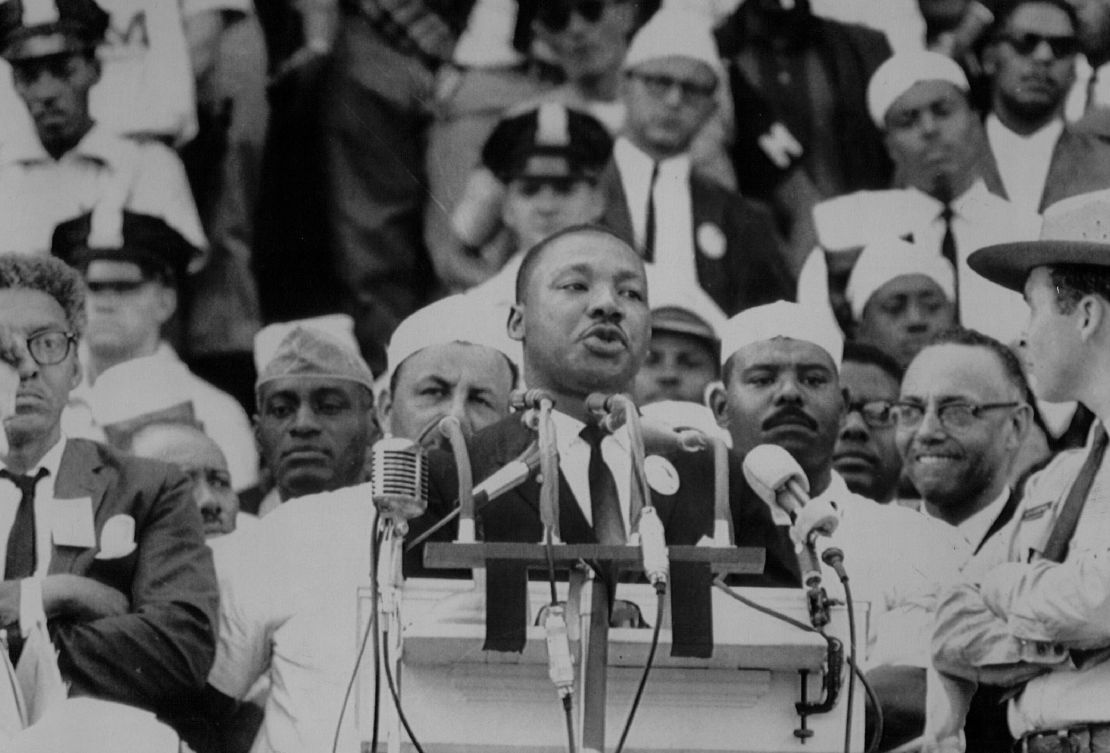

Rustin was a great organizer because he paid attention to details. He knew how many sandwiches and portable bathrooms the March on Washington participants needed. He knew how to raise money, how to charter buses to Washington and how to negotiate with sound engineers to make sure King’s voice could be heard across the Mall when he delivered his climatic “I Have a Dream” speech.

Watching Rustin organize the march in the film felt more exciting than the film’s depiction of the march itself.

There’s a scene in the movie where Ella Baker, one of the leaders of the civil rights movement who never got her due because of her gender, tells Rustin about the Ying and Yang every movement needs: a person in front and a logistical master behind the scenes. She sees that in Rustin’s partnership with King.

“On your own, you and Martin are fine,” she tells Rustin. “But together, you are fire.”

Lesson 3: Action without hope is impossible

The author Rebecca Solnit once wrote: “Hope calls for action; action is impossible without hope.”

Solnit says some of the biggest enemies of social change are cynicism and pessimism. Opponents of movements often try to convince demonstrators that they have no reason to expect they could win.

But Rustin had an ability to inspire marginalized people to believe they could win. One of the best passages in the film shows him molding a group of young, Black, brown and White civil rights activists into the crack team that would organize the March on Washington.

Rustin’s exuberance reflected the spirit of his time. He lived in another America full of can-do spirit. The country had defeated fascism during World War II; rebuilt Europe, pledged to send a man to the moon and wipe out poverty with President’s Johnson’s Great Society program. That optimism seeps through the movie.

Some of that patriotism may seem na?ve now, but it furnished the civil rights movement with tremendous vitality. There are scenes in the film of Rustin mobilizing his young volunteers that conjure memoires of former President Obama’s first campaign, when young people across America bonded together for “hope and change.”

At one point in the film, a young organizer proposes a wild idea, and while others shout the person down, Rustin praises the volunteer.

“Don’t stifle an impulse before it’s born,” he shouts with a huge smile.

Optimism was a core organizing principle for Rustin, says Puddington, who is also a senior scholar emeritus at the Freedom House, a group that defends human rights and promotes democratic change throughout the world.

“Bayard was among those rare individuals who believed that if your cause was just and you had access to the basic tools of democracy, your time would come,” Puddington wrote in an essay about Rustin.

“For gay people today who live in democratic settings, Bayard’s optimism has been validated with each new victory for equality.”

Rustin refused to be defined by his race or sexual orientation

There is one risk that comes with renewed appreciation of Rustin: It’s easy to short-change his complexity. He’s invariably defined primarily through his sexual orientation – something his enemies often did.

But Rustin said his faith as a Quaker was central to his identity.

“My activism did not spring from my being Black,” he once said. “It is rooted fundamentally in my Quaker upbringing.”

Rustin said those Quaker values were built “on the concept of a single human family,” and that racial injustice was a challenge to that belief.

“It demanded my involvement in the struggle to achieve interracial democracy, “he said, “but it is very likely that I would have been involved had I been a White person with the same philosophy.”

Rustin has been called many labels: a great civil rights activist, a gay pioneer, an “American Gandhi,” and “Mr. March on Washington.” Maybe it’s time we call simply describe him the way the author Cathy Young once did in an essay:

As “a great American and a true hero.”

John Blake is the author of?“More Than I Imagined: What a Black Man Discovered About the White Mother He Never Knew.”