Editor’s note: Sign up for CNN’s Wonder Theory science newsletter.?Explore the universe with news on fascinating discoveries, scientific advancements and more.

Scientists have grown kidneys containing mostly human cells inside pig embryos, an important step toward growing kidneys and potentially other human organs that could be used for transplants in people.?

The technique, described in a new study published Thursday in the scientific journal Cell Stem Cell, entails altering the genetic makeup of pig embryos and then injecting human cells that will go on to make a kidney inside the animals. The researchers involved said it’s the first time scientists have been able to grow a solid humanized organ inside another species.

The embryos, when implanted in surrogate pig mothers, began to grow kidneys containing mostly human cells that had a normal structure after 28 days of development, according to the study.

“It took us five years,” said senior study author Miguel Esteban, principal investigator at the Guangzhou Institute of Biomedicine and Health, Chinese Academy of Sciences.

“We modified the pig genetically to create a space for the human cells to grow with less competition from pig cells, and we also modified the human cells to make them survive in an environment that was not their natural one,” Esteban said via email.

Kidneys are the most commonly transplanted organs in humans, with more than 88,500 people waiting for a transplant in the United States, according to the Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network.

The goal of the experimental research is to use this technology to make organs from an individual patient’s cells, with pigs essentially serving as incubators, resulting in a much-reduced risk of rejection. However, it could take years and would be a complex process, the authors emphasized.

“Ultimately, we would like to produce mature human organs that can be used for transplantation or disease modelling, but this will take time and we will likely face additional technical barriers as we move forward,” Esteban said. “Nevertheless, we think it is possible.”

The team is also working to generate other human organs in pig embryos, including the heart and pancreas.

“The paper describes pioneering steps in a new approach to organ bioengineering using pigs as incubators for growing and cultivating human organs,” said Dusko Ilic, a professor of stem cell sciences at King’s College London, in a statement. He was not involved in the research.

Chimera organism

It’s not the first time that scientists have created a human-pig chimera — an organism containing DNA from two different species named after the mythical Greek monster. A team of scientists including Jun Wu, associate professor at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, did so in 2017. Wu called the latest study “encouraging” and “important.”

Mary Garry, a cell biologist at the University of Minnesota’s Lillehei Heart Institute, has created part-human and part-pig embryos with human muscle tissue and endothelium, a membrane that lines blood and heart vessels. She was not involved in the study.

“It’s the first time that a humanized kidney has been reported and it is important that each organ model is fully characterized,” she said. “It is imperative, however, that the tissue/organ is definitively proven to be human and, in this study, that is currently unclear.”

Esteban said there were also pig cells in the humanized kidney, but the human cells dominated, accounting for 60% to 70%.

“It is remarkable to see about 60% of the primordial pig kidney contained human cells,” Wu said. “In our study, the human cell contribution level is very low, and this study succeeded in improving human cells’ chimeric contribution, and more important (concentrated) them in the kidney.”

If gestation were allowed to continue further, Esteban added, it is possible that the proportion of human cells in the kidney would increase and potentially form the entire organ except the vasculature.

“Ultimately, producing mature kidneys (with) all cells being human would require further genetic manipulation of the host pig embryo, but it can be done,” he said.

What the researchers did

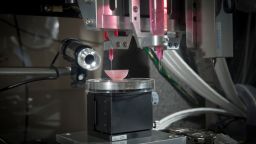

To generate kidneys mostly composed of human cells in pigs, the scientists used cutting-edge techniques harnessing advances in stem cells, gene editing and embryology.

First, they used CRISPR gene editing to alter the genetic makeup of pig embryos so that they were missing two genes necessary for kidney development.

Second, the researchers engineered human pluripotent cells — which are widely used in biological research and can be developed into any kind of human cell — so that they resembled early human embryonic cells and injected them in the altered pig embryo.

Third, the researchers figured out the optimal lab conditions to provide the right nutrients and signals to both the human and pig cells, which have different needs. After six or seven days, they then implanted the developing embryos in surrogate sows for 28 days.

“Making the cells adapt to the pig embryo environment and differentiate faithfully into the kidney lineage was challenging,” Esteban said.

When transferred into surrogate pig mothers, the developing humanized kidneys had “normal structure and tubule formation” after 28 days, the team said.

“It is a kidney in the middle stage of development, and hence underdeveloped, not a mature kidney,” Esteban said. “Yet, this is a very big step forward as it encourages us and other researchers to think that it is possible to produce a mature kidney once other technical obstacles are solved.”

Ethical considerations

Ethical considerations surround this type of research. These include animal welfare and concerns that human cells could become involved in not only forming the kidney but other tissues inside the pig, such as its brain, raising the possibility the experiments could affect the animal’s behavior.

“The main concern would be if there was much contribution of human cells to undesired lineages and the pigs were brought to term, which we obviously didn’t do either,” Esteban said.

“It is very important to note that there was very little contribution of human cells to other lineages apart from the kidney. We saw very few human cells in the central nervous system and none in the germline (reproductive cells).”

He added, “We are very thoughtful with what we do and are moving very cautiously and step by step with this research to avoid any ethical controversy.”

A different approach to xenotransplantation

The work of Esteban and his team is a different approach from xenotransplantation — the use of nonhuman tissues or organs to treat medical conditions in humans.

In recent years, at least two separate teams of researchers have transplanted pig kidneys into brain-dead humans. However, more work is needed, including studies in living human recipients, to establish whether pig kidney transplants could be a lifeline for people with end-stage kidney disease.

“This (new) work is different from existing xenotransplantation approach and aims to generate organs mostly composed of human cells in pigs,” Wu said.

“It will be advantageous in future studies to combine the two and enrich genetically modified pig organs with human cells to make them more human-like.”

Joseph A. Vassalotti, chief medical officer at the US National Kidney Foundation and a clinical professor at Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, said that while these approaches inspire wonder and excitement, the latest research is an incremental step in a long process.

“I commend the researchers for conducting complex and fascinating research, we have to understand the overall perspective,” Vassalotti said via email. “If developing a ‘humanized’ kidney in a pig and transplanting it into a human is like a ten-story building, then perhaps investigators have added several bricks.”