Editor’s Note: Sign up for CNN’s Wonder Theory science newsletter.?Explore the universe with news on fascinating discoveries, scientific advancements and more.

With appendages growing out of its head and an armored mouth, an ancient shrimplike creature was thought to be the quintessential apex predator of its time.

This sea creature earned its fearsome reputation because paleontologists thought it was responsible for the scarring and crushing of the fossilized skeletons of trilobites — early hard-shelled invertebrates that skittered along the seafloor before dying off in the mass extinction that gave way to the dinosaurs.

The 2-foot-long (0.6-meter-long) Anomalocaris canadensis was one of the largest marine animals to live 508 million years ago. The underwater hunter prowled the seas during the Cambrian period — a critical juncture in the planet’s history?when there was an explosion in the diversity of life and many major animal groups alive today emerged.

“That didn’t sit right with me, because trilobites have a very strong exoskeleton, which they essentially make out of rock, while this animal would have mostly been soft and squishy,” said lead author Russell Bicknell, a postdoctoral researcher in the American Museum of Natural History’s division of paleontology, who conducted the work while at the University of New England in Australia.

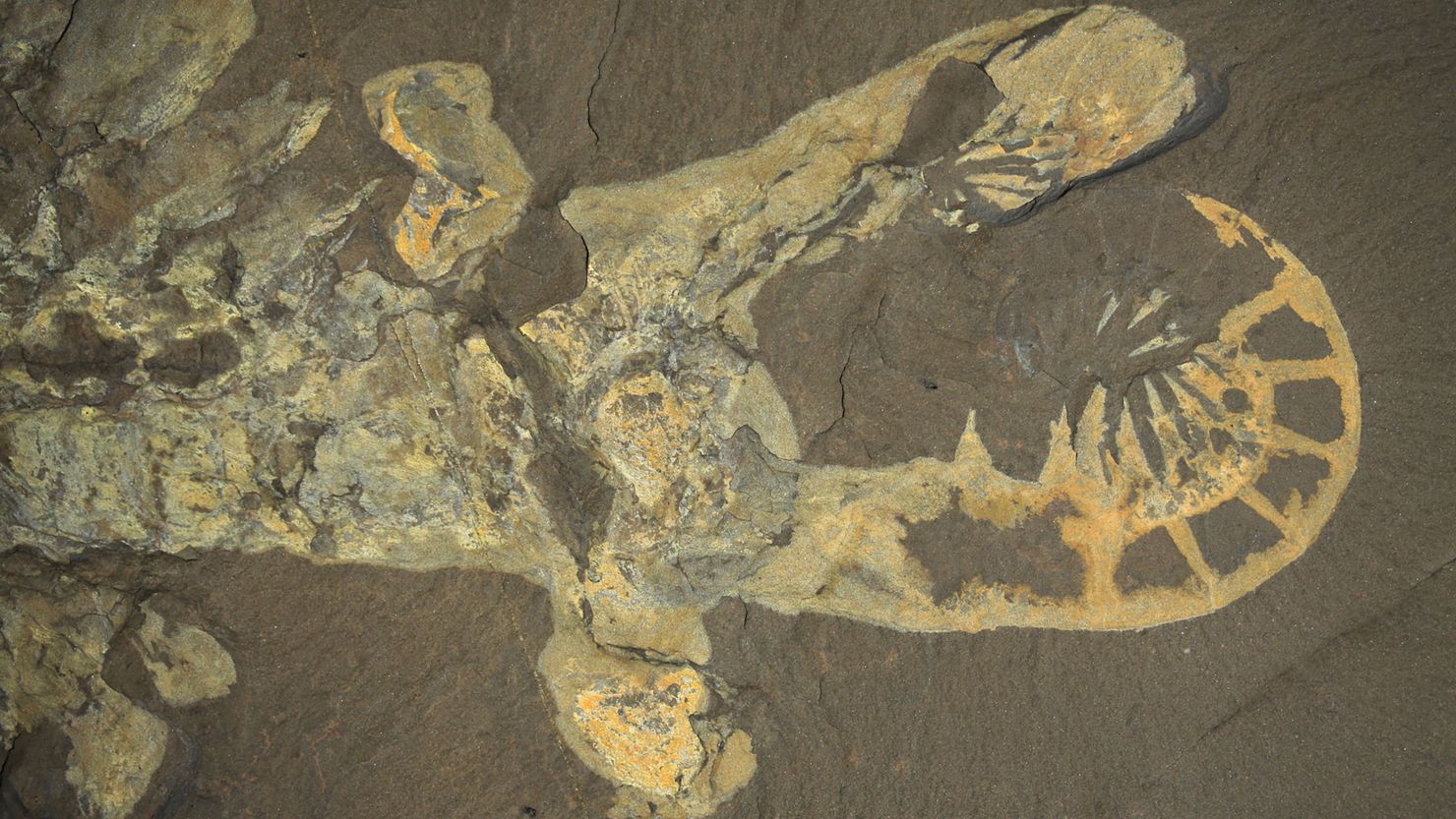

Bicknell and his collaborators in Germany, China, Switzerland and the United Kingdom have created a new three-dimensional reconstruction of the creature, using computer modeling to better understand its biomechanics. The model was based on a well-preserved but flattened fossil found in the Burgess Shale formation in the Canadian Rockies.

Hunting with long appendages

Earlier research had suggested that Anomalocaris’ mouth parts weren’t able to process hard food, so Bicknell and his colleagues focused on whether its long and spiny appendages would be able to chew up trilobite prey.

Using present-day whip scorpions and whip spiders as analogs because they sport similar appendages that allow them to grasp prey, the study team was able to show that the predator’s segmented appendages were able to grab prey and could both stretch out and flex.

However, the team’s analysis suggested the marine animal was more of a weakling than initially assumed and was “incapable” of crushing hard-shelled prey with the two structures, according to the study published Tuesday in the journal Proceedings of the Royal Society B.

It’s more likely the creature, which Bicknell described as being a cross between a shrimp and a cuttlefish, was probably agile and fast and darted after soft prey in well-lit open water rather than pursue hard-shelled creatures on the ocean floor.

“Previous conceptions were that these animals would have seen the Burgess Shale fauna as a smorgasbord, going after anything they wanted to, but we’re finding that the dynamics of the Cambrian food webs were likely much more complex than we once thought,” Bicknell said in a statement.