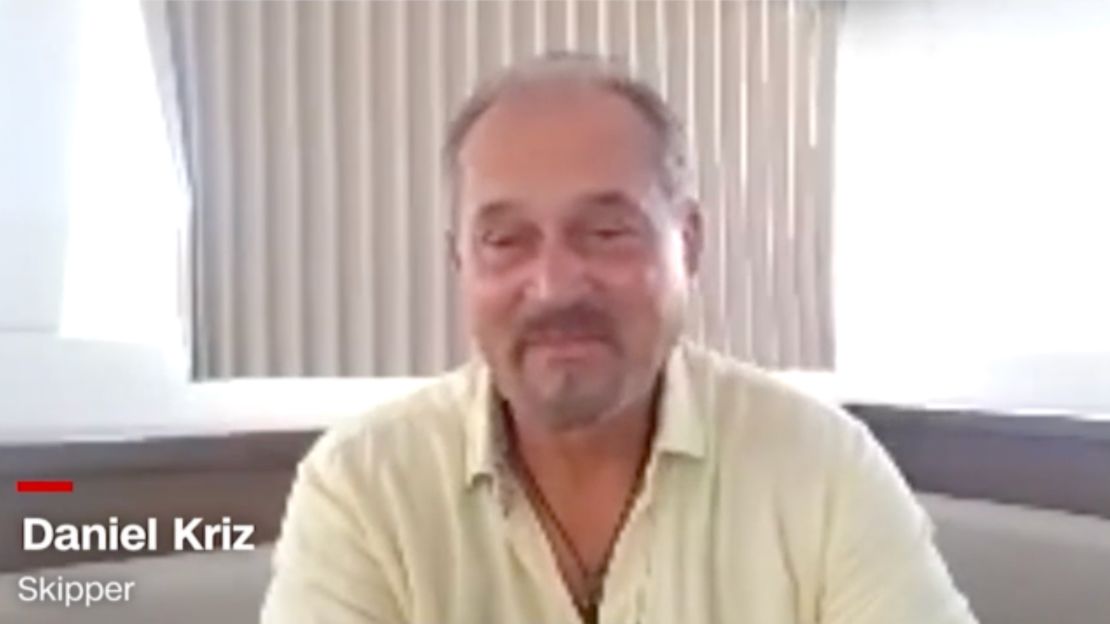

When Daniel Kriz saw a pair of killer whales underneath his boat while crossing the Strait of Gibraltar in April, he thought: “Not again.”

For Kriz, a veteran skipper who was delivering a racing catamaran across the Atlantic, it was the second such encounter in three years, after a pod of orcas had surrounded and disabled his boat in 2020.

“We were suddenly surprised by what felt like a bad wave from the side,” he said of the recent incident. “That happened twice, and the second time we realized that we had two orcas underneath the boat, biting the rudder off. They were two juveniles, and the adults were cruising around, and it seemed to me like they were monitoring that action.”

The four people on board the vessel didn’t suffer any injuries, but without full control of the boat, Kriz had to reach the nearest marina using only his engines. The whales had destroyed both rudders — the submerged control surfaces that steer a boat — in what seemed like a streamlined version of the encounter that occurred three years prior.

“In 2020, the attack lasted almost an hour and was not as organized,” Kriz said. “This time we could hear them communicating under the boat. It only took about 10 to 15 minutes.”

Kriz’s experience isn’t an isolated one. In the past three years, the Strait of Gibraltar — an 8-mile-wide (13-kilometer-wide) sea corridor separating Europe from Africa — has been a hot spot of activity, with over 500 interactions between orcas and boats.

All of the encounters involve some combination of the same roughly 15 animals, which have sunk three vessels and disabled dozens more, according to Mónica González, a marine biologist with CEMMA, or Coordinadora para o Estudo dos Mamíferos Mari?os, a nongovernmental organization that is gathering data about the orcas in the strait.

The reason why certain whales are taking such a forward interest in boats is still unclear, but experts have a couple of theories.

Two theories

The Strait of Gibraltar is one of the world’s busiest waterways, and while orcas only approach a tiny fraction of the boats that go through, about 1 in 5 interactions result in severe damage requiring a tow, González said.

The latest sinking occurred in early May, when the sailing yacht Alboran Champagne was attacked by three orcas and completely flooded; it was then abandoned and left adrift to sink. As recently as June 22, two different teams participating in the annual Ocean Race sailing event reported run-ins with orcas in the strait, but neither yacht sustained damage.

The current rate of interactions is at a seasonal peak of about 20 to 25 per month: “There are more encounters in the summer because the orca’s prey, bluefin tuna, is in the strait, so they are waiting there,” González said. “When the summer ends, the tuna moves to the north of Spain and the orcas follow them.”

Killer whales are the largest members of the dolphin family. The powerful animals are highly social sea mammals and can swim at speeds of up to 30 miles per hour (48.3 kilometers per hour), according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. An adult can weigh up to 11 tons and reach 32 feet (9.7 meters) in length. Individual orcas can live as long as 90 years in the wild, and the global population is estimated at around 50,000.

González said that the total number of killer whales in the strait is just 40 — a subpopulation listed as critically endangered by the International Union for the Conservation of Nature — with about 15 approaching boats. And among the offenders, there are only two adults, which might offer clues to their motivation.

“We have two theories about why these interactions started,” she said. “The first is that the orcas are just playing, and the other is that one animal suffered an aversive moment and the orcas are trying to stop the boats to prevent it from happening again — but we don’t know exactly what happened in the first place.”

White Gladis

In 2022, researchers from a number of local institutions and universities conducted a study on the attacks, revealing that they typically happen in daylight, mainly around noon, and last between half an hour and two hours.

The average size of the vessels approached is about 40 feet (12.2 meters), and the usual pattern for an interaction involves the orcas approaching the boat silently, swimming under it, lightly touching it and then — in the most extreme cases — going for the rudder.

When the animals do, they can quickly make a boat pivot 360 degrees, causing danger and distress to its occupants. The encounter usually ends once the killer whales break the rudder or the boat comes to a complete stop.

“It is increasingly likely that an animal has started this behavior after an incident with a boat,” said biologist Alfredo López Fernandez, an adjunct researcher at the University of Aveiro in Portugal and one of the authors of the study. He points to the history of a female orca known as White Gladis as evidence: “She is the only adult who started in 2020 with the interactions along with seven other juveniles.”

There are clues suggesting that White Gladis may have become entangled in fishing gear — a common threat to orcas — either as an accident or during an illegal fishing attempt, López Fernandez said: Many boats use fishing lines at the stern, and this seems to be one of the motivating factors for orcas to approach and investigate the rear of the craft. Earlier this year, another killer whale in the area was spotted with a fishing line on its body, he said.

Since White Gladis’ supposed traumatic event, two adult killer whales may have started teaching juveniles how to approach boats to disable their rudders — which seems to track with Kriz’s observation about the evolution of the behavior between his two encounters.

“Orcas are a very matriarchal society and all juveniles look up to these very important females in the pod; the juveniles are copying their behaviors because they believe that if these very important individuals do something, they have to do the same to ensure their own survival,” González said.

Worryingly, the interactions seem to be on the rise: “From January to May, we’ve seen an increase compared to last year, but it’s too early to say if this will be maintained throughout the rest of the season,” López Fernandez said.

No harm to people

According to Hanne Strager, a marine biologist and author of “The Killer Whales Journals,” while the traumatic origin of the behavior can’t be ruled out, she also believes that play is a more viable explanation.

“They are attracted to the rudder, because it is built to be movable and they found out that if they push it to the side they can make cracks in the hull — and that’s what is believed to be the cause of the sinking of some of these boats,” she said.

“They may think it’s fun — like kicking a ball onto a lawn to see what happens. But for the people who are experiencing this on their multimillion dollar boat, it’s not fun, it’s not play. It’s pretty scary.”

However, there’s no evidence that the whales want to harm humans, Strager added.

“I’ve spoken to one of the crew members of one of the boats that went down, who is also a marine biologist, and he said he never felt that there was any aggression,” she said. “They didn’t care about the people, and as soon as the boat sank, they went away.”

Kriz also ruled out any openly hostile intent on the mammals’ part.

“I don’t think this is aggressive behavior and definitely not towards the humans. They basically play with the rudders until they get them off,” he said. “They could see us — we were filming and taking pictures of them from the boat and there was no interaction at all from either side. They didn’t bump the boat in any other place. Just the rudders.”

Play behavior

Killer whales are highly intelligent and known for playful behaviors, which can sometimes turn into cultural fads among a small group of individuals. González mentioned how in 1987, in the waters of the Pacific Northwest, one orca started carrying dead salmon on her head, and the behavior quickly spread to the rest of the pod, only to last a year.

“They certainly do play and they play with all kinds of things,” Strager said. “I’ve seen them swimming around with a jellyfish on the nose for a while. Several of them did this and there was no explanation other than it was fun. I’ve also seen them whack small seabirds from the water surface, which they are not eating afterwards. They also play with each other.”

Boats crossing the Strait of Gibraltar are advised to check the Atlantic Orca Working Group’s website and download an app called GT Orcas to find out about hot spots of activity that are best avoided. In case of an encounter, it’s best to do nothing.

“The official recommendation is not to do anything at all, turn off the engine or lower the sails and be as uninteresting to the killer whales as possible. Don’t yell, don’t shout, don’t scream,” Strager advised.

For the critically endangered whales, getting a bad reputation could be fatal. “Some sailors are recommending that you throw chloride, diesel, firecrackers or even dynamite in the water,” Strager said. “But this very vulnerable little population of killer whales depends on our love for them. They depend on our protection.”

Kriz agreed. “Bottom line, we are in their territory,” he said.

“Maybe we should designate some kind of corridor where boats enter or exit Gibraltar, something like shipping lanes,” he added, noting that tracking the animals’ location only works up to a point because “they’ve been all around.”

Is it likely that the whales will get bored of smashing rudders anytime soon? Don’t bet on it, González said. “Personally I don’t think they are going to stop soon,” she said. “Maybe little by little, but not in the short term.”