Editor’s Note: A version of this story appears in CNN’s Meanwhile in the Middle East newsletter, a three-times-a-week look inside the region’s biggest stories. Sign up here.

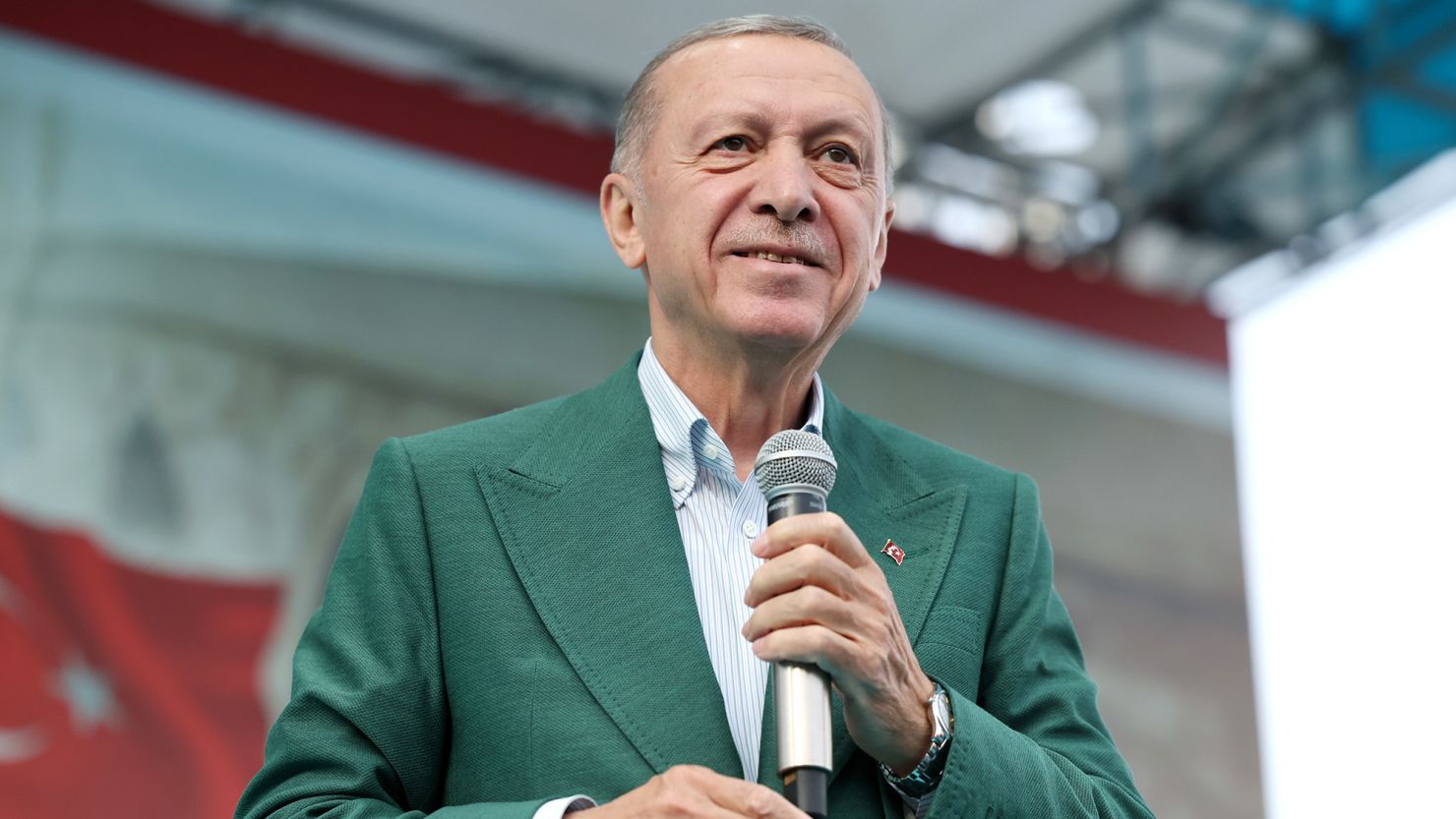

Turkish leader Recep Tayyip Erdogan’s rise to power was ushered in by the contentious political aftermath of the 1999 Izmit earthquake. So when another devastating quake laid waste to large swathes of southeast Turkey earlier this year, many observers expected the president’s two-decade rule to end with a full circle.

Instead, Erdogan appears to have defied the odds.

The first round of Turkey’s presidential and parliamentary voting on May 14 made him the frontrunner in the race that pollsters predicted could unseat him.

He won a nearly five-point lead over his principal rival, opposition leader, Kemal Kilicdaroglu, and fell less than half a percentage point short of the 50% threshold required for victory. His parliamentary bloc won a comfortable majority in the legislature.

This week, the third-place presidential candidate Sinan Ogan, publicly endorsed Erdogan, further boosting his chances against Kilicdaroglu in the run-off election on Sunday.

“It will be the people who will be the kingmakers, and when the people decide, I believe they will stand with those who have successfully served the Turkish nation for the last 21 years,” Erdogan told CNN’s Becky Anderson in an exclusive interview last week.

During that interview, the president tried to burnish his credentials, skirting over the country’s years-long financial crisis and his government’s shortcomings in rescue operations after the catastrophic February earthquake.

He dismissed the 74-year-old Kilicdaroglu as a political amateur. The two rivals have fashioned their campaigns as an array of contrasts. While Erdogan aimed to showcase his political prowess and repeatedly touted Turkey’s rapidly growing defense industry, Kilicdaroglu presented himself as the quintessential technocrat: softspoken, level-headed and conciliatory.

Six right- and left-wing opposition groups united behind Kilicdaroglu in an unprecedented bid to unseat the sitting president, and cast a wide net over Turkish voters. They hoped to seize on public disgruntlement over a floundering economy and the aftermath of the quake. Erdogan, on the other hand, focused on reinvigorating his conservative strongholds.

The men concluded their election campaigns with a similar public flourish. Erdogan prayed at the Hagia Sophia, the Istanbul mosque and former church which the Turkish government in 1934 turned into a museum out of respect for both its Byzantine and Ottoman histories. Erdogan controversially annulled that decision in 2020, one of the many populist moves that have peppered his career.

Deepening polarization

Meanwhile, Kilicdaroglu marked the eve of the vote by laying flowers at the tomb of Mustafa Kemal Ataturk, the founder of the Turkish Republic who spearheaded the secularization of the country.

The optics seemed to mirror Turkey’s deepening polarization.

A religious fervor underpins much of Erdogan’s support, which appears to have barely been dented by the flailing economy or the government’s shambolic early response to the earthquake, exacerbating a tragedy that claimed over 50,000 lives in Turkey and neighboring Syria.

Outside AK Party headquarters on the night of the first round of presidential votes, that religious sentiment was widespread. “I am afraid. I am worried about him losing,” said Seda Yavuz, a visibly nervous Erdogan supporter. “I am worried that someone else will win. I worry because we are Muslims and we wish for someone Muslim to be our president.”

“I trust the Turkish people. I trust that he is going to win,” another woman, Gozde Demirci, told CNN’s Jomana Karadsheh.

“This is freedom,” said the impassioned Demirci, pointing to her headscarf. Erdogan lifted restrictions on hijab in the public sector in 2013, hailing it as the end of a “dark time.”

“I have this freedom because of him (Erdogan),” she continued. “They (the opposition) don’t want this. They don’t want freedom.”

That support for the sitting president was not properly captured by pollsters and Western media, Mehmet Celik, editorial coordinator of the pro-Erdogan Daily Sabah newspaper told CNN.

“I think that there was this groundswell that pushed Erdogan’s vote,” Celik said. “He was able to gather 49.5% of the vote, despite all the challenges. Despite the fact he has been running for 21 years. There is this fatigue. (But) he is still very popular.”

Erdogan’s critics argue that he further galvanized his support base by levelling unsupported allegations at the opposition camp. He accused Kilicdaroglu of colluding with Kurdish terror groups and repeatedly referred to the opposition leader — a member of the liberal Muslim Alevi minority — as a not-good-enough Muslim.

“This strategy of ‘not good Muslim and backed by terrorists’ appealed to right-wing voters that were supposed to pick Kilicdaroglu,” said Soner Cagaptay, senior fellow at the Washington Institute for Near East Policy.

Downward trajectory

Cagaptay argues that while Erdogan’s message did not resonate in Turkey’s big cities and the relatively affluent southern coastline, all of which voted largely for the opposition, it garnered necessary support from poorer parts of the country, namely in central regions and on the Black Sea coast.

“There, support for Kilicdaroglu was suppressed because right-wing voters whose own parties backed Kilicdaroglu did not pick him,” he said.

Erdogan’s messaging was amplified by his broad sway over Turkish media, critics argued.

“President Erdogan shouldn’t be underestimated because he’s always using political tactics in a very vile way,” said Seren Selvin Korkmaz, executive director of the Istanbul-based InstanPol Institute. “By using the state resources and overall media power he has assured that he is the only one in the political game. The playing field was not fair.”

Still, the president is on an overall downward trajectory. Sunday’s run-off is a first-ever presidential second round in Turkey. In 2019, Erdogan’s ruling party lost the major cities in mayoral elections, including his own hometown, Istanbul. On May 14, the majority of Istanbul’s votes went to the opposition.

Erdogan once reportedly said, “If we lose Istanbul, we lose Turkey,” and the political status of the country’s biggest city is a personal sore point in the president’s career.

“He’s really hurting to take Istanbul,” Cagaptay said. “He loves Istanbul because it symbolizes Ottoman power and Erdogan’s power agenda… He wants to make Turkey great again. He wants to restore Ottoman greatness.”

For now Erdogan seems poised to survive Turkey’s political and tectonic shifts. He has also vowed to double down on the policies that have consolidated his rule, but exacerbated the country’s current woes.

“The question is not ‘will he win’ (on Sunday) but what kind of win will it be,” Cagaptay said.

If Erdogan wins by a landslide, Cagaptay added, “he will be vindicated on unorthodox economic policies, lack of rule of law and the end of social autonomy.”