Sign up for CNN’s Wonder Theory science newsletter. Explore the universe with news on fascinating discoveries, scientific advancements and more.

Nature documentaries have never been more visually breathtaking — drone footage and high-definition photography make watching animals in their native habitats a majestic spectacle.

What’s sometimes lost in this feast for the eyes is the sonic world of animals — audible to humans in the case of birdsong. For other animals such as bats, whales and other undersea creatures, their sounds exist in a realm beyond our sensory bubble.

A new exhibition that opened April 21 at the British Library in London explores how animals have been documented over the past 2,000 years. The show makes the case that sound is just as instrumental as sight when it comes to our understanding of the natural world.

“Animals: Art, Science and Sound” showcases the British Library’s wildlife collection, which contains over 250,000 recordings of animals from around the world. The recordings have been used to create four unique soundscapes representing darkness, water, land and air. Individual recordings are on display in the exhibition.

Most poignant is the song of the last Kaua?i ?ō?ō, a songbird from Hawaii. Habitat destruction and invasive species, which were introduced to the Hawaiian island of Kaua?i over the past 100 years, reduced the once thriving population to a single pair. In 1982, the female bird died during a hurricane, leaving behind her male partner. It is his solitary song that can be heard here, calling out to his mate who will sadly never respond.

The species was declared extinct in 2000.

Bats’ sixth sense

Naturalists had long understood that bats must communicate in some way — 18th century Italian scientist Lazarro Spallanzani put an owl and a bat in a completely dark room and found that while the bat flew effortlessly, the owl kept bumping into objects in its flight path. He believed a mysterious sixth sense allowed bats to navigate without colliding with obstacles and hunt tiny insect prey in complete darkness

But the principle of echolocation — which bats use to emit ultrasound pulses that are too high-pitched for humans to hear — wasn’t discovered until 1940 by US biologist Donald Griffin.

Amateur British naturalist John Hooper developed a portable bat detector and made the first recordings of Great Britain’s bats. His equipment and the audio it captured are both featured in the exhibit. Hooper’s work helped prove that different species of bats echolocated at different pitches, allowing bats to be identified by sound alone.

The exhibition also includes the first published recording of an animal — a nightingale’s song released in 1910 by the Gramophone Company Ltd. that allowed people to hear birdsong in their own homes.

The groundbreaking release marked the beginning of commercial wildlife recording that culminated in the 1970s. A recording of humpback whale song was distributed with the January 1979 issue of National Geographic magazine and became the largest single pressing of a commercial record — over 10 million copies were made. Recordings of whale song such as this megahit helped galvanize the era’s “Save the Whales” movement, explained Cheryl Tipp, curator of Wildlife and Environmental Sounds at the British Library.

“Sound recording has allowed us to uncover aspects of animal lives that just would not have been possible using textual or visual methods alone,” Tipp said.

“It has been used to reclassify species, locate previously unknown populations and allowed us to eavesdrop on worlds that would otherwise be inaudible to our ears.”

Zoological treasures

Curators combed the British Library for zoological treasures. The staff dug up the earliest use of the word “shark” in printed English from 1569 and Leonardo da Vinci’s notes and sketches (1500-1508) on the impact of wind on a bird in flight, both of which are on public display for the first time. More recent documents include the first Red List of Threatened Species from 1965.

Stunning contemporary insect portraits by photographer Levon Biss of beetles collected by Charles Darwin in 1836 and his collaborator Alfred Russel Wallace circa 1859 are shown alongside the original specimens.

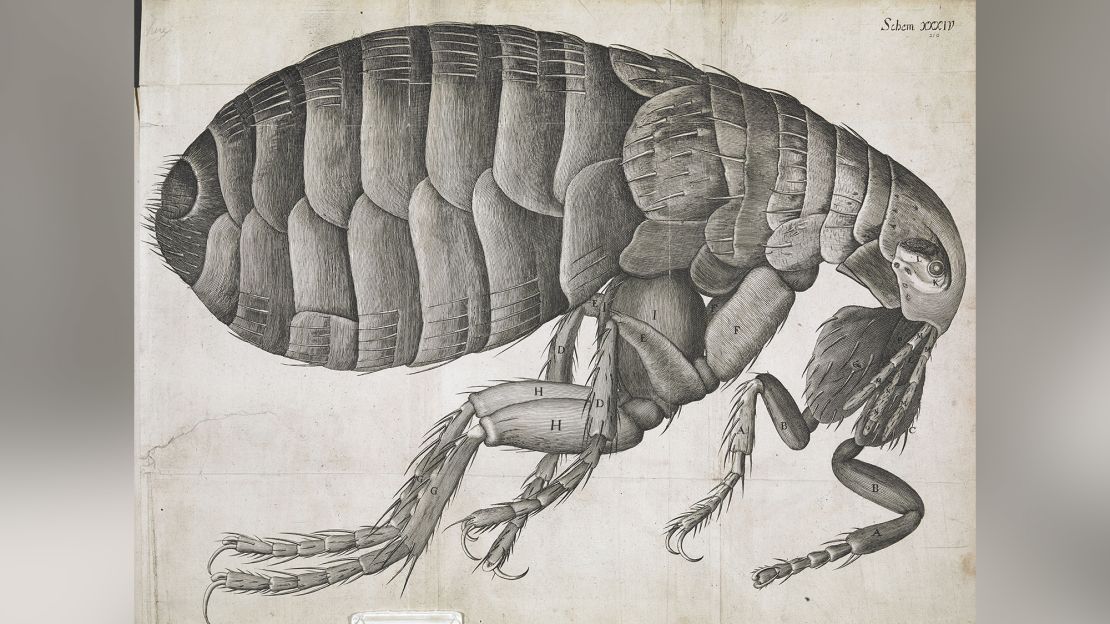

Rare and sumptuously illustrated wildlife books on display include Robert Hooke’s “Micrographia.” Published in 1665, it was a landmark work on the microscopic world that catapulted observations made under microscopes to the wider world for the first time. Even though the title was published the same year a plague outbreak gripped London, it took another two centuries before it was understood that microorganisms we know as germs caused disease.

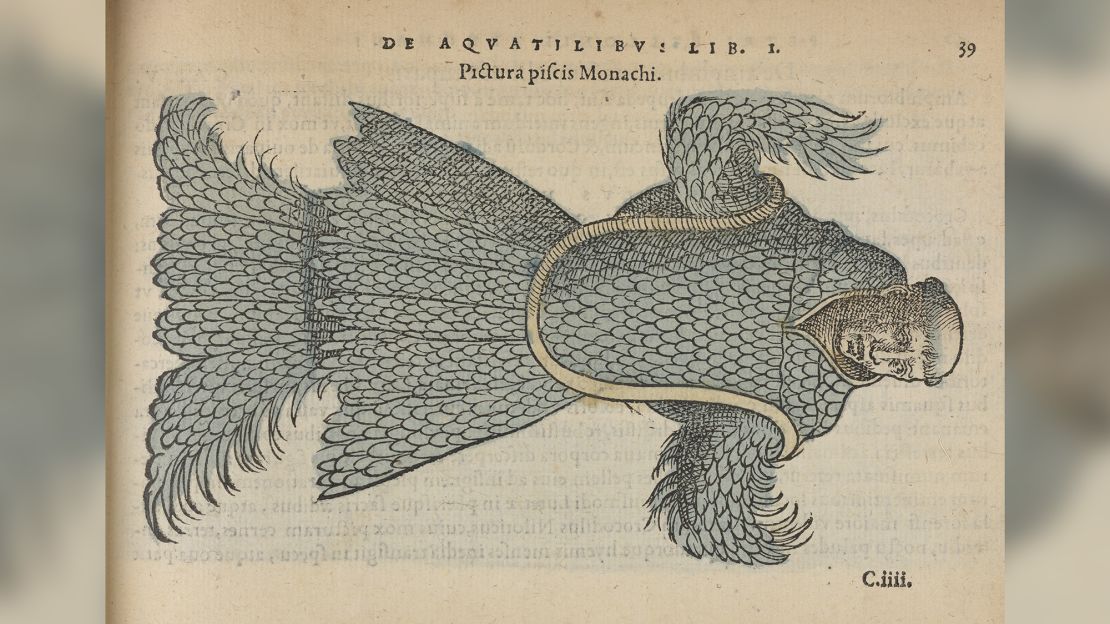

The surprisingly lifelike illustrations of Britain’s freshwater fish by pioneering 19th century female naturalist Sarah Bowdich — who painted each fish minutes after it had been plucked from the water — stand in contrast to some fun instances where early scientific illustrators got it spectacularly wrong.

“Animals: Art, Science and Sound” is at the British Library in London until Monday, August 28.