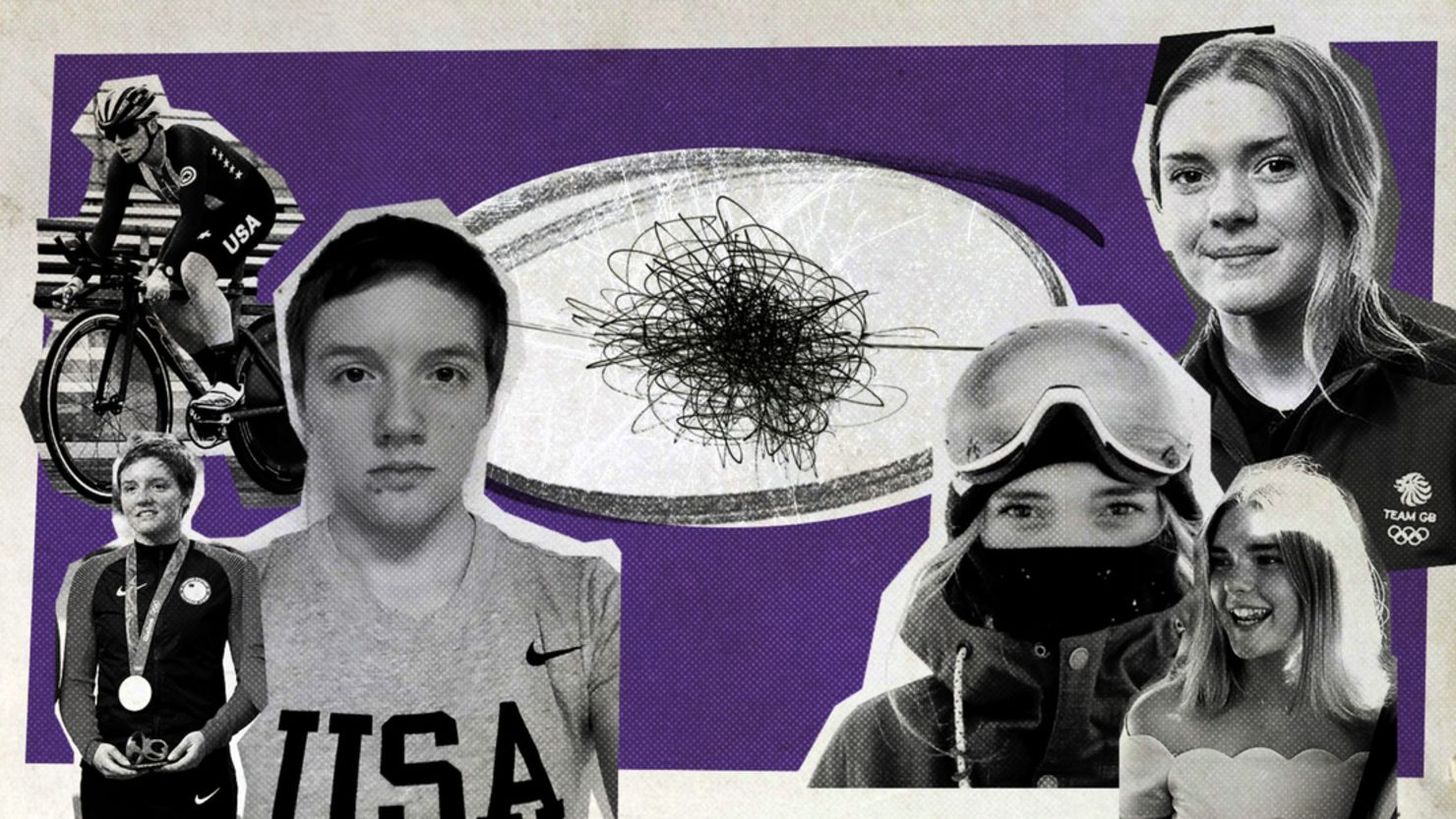

Kelly Catlin and Ellie Soutter never met, but they had a lot in common.

Both were commanding athletes: Catlin, a US track cyclist, was a three-times world champion and Olympic silver medalist, and Soutter, a snowboarder, was tipped to be one of Team Great Britain’s strongest contenders for the 2022 Winter Olympics, having already won a bronze medal at the 2017 European Youth Olympic Festival.

Both were incredibly smart – Catlin was studying for a master’s degree in computational and mathematical engineering at Stanford University, while Soutter learned to speak French in about six months, according to her father.

At times they almost seemed superhuman. In 2013, after only three weeks of formal training and having broken her wrist, Soutter became British Champion with her arm in a cast. Meanwhile, Catlin, who had a tenderness for children, once rode 80 miles through sleet and snow to speak to a grade school about her Olympic experience.

Yet these two women’s lives were tragically cut short after they sustained serious head injuries in their pursuit of sporting greatness and then took their own lives. Catlin was 23, while Soutter died by suicide on her 18th birthday.

Females may be more susceptible to concussion, and they also have worse and prolonged symptoms after their injury than men, according to a review of 25 studies of sport-related concussion published in the Orthopaedic Journal of Sports Medicine.

However, women remain significantly underrepresented within sport and exercise science research. This, leading experts warn, means they often do not get the treatment or aftercare they need following a head injury.

Women’s sports have historically not received the same attention or funding as men’s sports, Dr. Ann McKee, Director of the Boston University Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy (CTE) Center told CNN.

“It’s been shown that women athletes are more likely to get a concussion, they tend to have longer recovery periods,” McKee added.

“We do not have enough information about what happens in the female brain. We don’t know if women are biologically more susceptible to these injuries,” she said, adding that some research suggests the size and musculature of women’s necks could play a part.

Kelly

Before becoming a track cyclist, Catlin, a triplet, was a national champion road cyclist and time trial national champion, her father Mark, told CNN. After winning a Canadian international race at 17 she was invited to an Olympic training camp for a try out, where, impressed by her performance numbers, coaches immediately offered her a position on the track pursuit team.

Catlin’s father, Mark, told CNN, that his daughter was “intense” and “ambitious,” attributes she channeled into her sporting life.

Her life changed irrevocably in January 2019. Practicing fast downhill descents in the hills near Los Angeles, she crashed and went skidding down the road. Despite suffering road rash, Catlin got back on her bike, and finished the ride. It wasn’t her first crash – she had experienced 4 or 5 hard crashes before this, her father said, and after the latest, she didn’t have any symptoms at the time.

But soon after, at a World Cup track event in Berlin, Catlin was gripped by a sudden and severe headache.

“She couldn’t compete,” her father said. “Kelly is kind of this stoical individual. And if she’s rolling around on the ground, clutching her head, it has to be a severe thing.”

On closer inspection, Catlin’s helmet from LA had dents in it. Her father told CNN that this, coupled with her symptoms, caused her family to become aware she had suffered a concussion, which was later confirmed with a diagnosis from Stanford’s Health Centre.

A concussion is a brain injury which happens after a hit to the head or body causes the brain to move back and forth inside the skull, according to the CDC.

When Catlin returned to the US, her father says she was examined by the track training center in Colorado. It was confirmed she suffered a concussion, and a return to training protocol was advised, but not implemented or communicated to her coach, he said.

“There wasn’t any follow-up from Colorado after this. I believe they assumed she would seek care at Stanford,” he told CNN.

CNN has reached out to Stanford and USA Cycling for comment.

Catlin’s symptoms didn’t improve, and in weekly phone calls with her parents, she admitted she was struggling with schoolwork and was unable to concentrate.

Stanford Health Center, having diagnosed Catlin with concussion with ongoing symptoms, recommended that she decrease her training for 2 weeks and then gradually build back up and start sessions with an athletic trainer, medical documents sent to CNN by her father show. She was referred to a concussion specialist, the document adds.

She tried to train, but “she would have to stop because she got a severe headache just from walking,” according to her father. Her heart rate would also accelerate rapidly from even the smallest exertion, leaving her with “no exercise tolerance whatsoever,” he added.

Her injury had other consequences.

“As far as we knew she was never a person that suffered from depression. She had an interesting sense of humor. She was always upbeat and bubbly about things,” her father told CNN.

“She basically thought her life was over. She was no longer able to be the athlete that she was, she was failing her teammates. And she wasn’t able to succeed in school now. And I think ultimately, that’s why she took her life, because she thought her life was over,” he added.

At the end of January, Catlin made a serious but non-fatal suicide attempt, and was involuntarily admitted to the locked psychiatric ward at Stanford, her father told CNN.

A month after that attempt, she took her own life.

Ellie

Soutter’s father Tony said there were many dimensions to his young daughter – not only was she an “adrenaline junkie,” but she was “very conscientious” and excelled in school, even after moving from England to France.

Aged 12, Soutter took up snowboarding at school – and just months later, she was spotted in her hometown resort of Les Gets and trialed by Team Great Britain in February 2013.

“It was quite obvious why she kept winning competitions because she just made it easy,” her father said. “She just made it look graceful and beautiful.”

But training took its toll – Soutter told CNN that his daughter suffered seven major concussions in five years, between 2013 and 2018.

“I was being advised by doctors “Oh, don’t worry, she’s young enough she’ll bounce back. As she progressed, becoming an elite athlete starting on the World Cup circuit, every time she had another concussion, they got worse, and they took longer to recover from,” he told CNN.

“With every concussion, with the exception of a few minor knocks, Ellie saw a doctor in person,” he added. “I was always told that she was young enough to bounce back to full health after each case and therefore never consulted with the doctors that I met, about any previous concussions.”

But Soutter’s final concussion was so “huge” that she spent two nights in the hospital.

“When I got there, she didn’t even know who I was or where she was,” her father said.

Soutter was then selected for the Junior Snowboard World Championships in New Zealand August 2018. But a month before the competition, she died by suicide.

Her father said a neurologist conducted a CT scan of her brain and reaction tests three months after her final concussion, but said she was “absolutely fine” and could continue competing.

Like Catlin, Soutter had issues with studying and concentrating, becoming more insular as she suffered from crippling headaches. She also started suffering from insomnia.

“She would literally sit with the tutor a good month after a concussion, and suddenly, she’d go blind. She’d not be able to see – everything would go black and dark,” her father said.

After missing a flight to snowboard training, Soutter died by suicide on her 18th birthday.

Team GB referred CNN to GB Snowsport when approached for comment, adding that Ellie only competed for Team GB at one event.

In order to represent Britain in international competitions, GB Snowsport says athletes or their coaches are required to demonstrate that the athlete has reached established performance criteria, is of the relevant technical ability to compete, and has appropriate medical clearance to compete. A large number of athletes can represent Britain at different levels of international competition but are not part of a programme delivered and overseen by GB Snowsport.

“As Ellie was not part of the GB Snowsport programme, we were unable to implement a personalised recovery and management programme for Ellie,” a spokesperson for GB Snowsport told CNN in an email.

“She was, however, covered by national policies and protocols around fitness to compete, and would not have been cleared for any activity – training or competition – overseen by GB Snowsport without being able to demonstrate appropriate medical sign-off,” they added.

The spokesperson for GB Snowsport told CNN: “We take concussions and head injuries incredibly seriously, and in reviewing contemporaneous records from the time that Ellie was involved in snowsport we are confident that GB Snowsport staff applied and followed every appropriate process.”

Catlin and Soutter aren’t the only young sporting women whose lives have been cut short in this way.

After 29-year-old Australian rules football player Jacinda Barclay took her life in 2020, post-mortem research by scientists found that she had degradation to her cerebral white matter unusual for someone her age.

“For someone her age, you would expect to see lovely pristine white matter, and hers looked like she was an old woman in that it was basically degraded,” Michael Buckland, founder and Executive Director of the Australian Sports Brain Bank, who studied Barclay’s brain, told CNN.

“We haven’t gone back and done specific white matter studies on our donors,” he told CNN, adding that the bank hasn’t done peer reviewed research on this. “But what struck me, just as someone that sees a lot of brains – this is not normal for someone of that age.”

Damage to white matter has been associated with dementia, according to research published in the Journal of the American Medical Association.

Opportunities missed

Suicide after concussion is rare. However patients diagnosed with concussion or mild traumatic brain injury had double the risk of suicide and a higher risk of suicide attempts and suicidal thoughts than people without brain injuries, a 2018 study from researchers at the University of Harvard published in JAMA Neurology found.

Dr. Robert Cantu, clinical professor of neurology at the Center for the Study of Traumatic Encephalopathy at Boston University School of Medicine told CNN that there are several theories as to why incidence of suicide is higher in people who have suffered concussion.

One theory, he explained, is that those suffering from persistent post-concussion symptoms may have structural or functional brain damage and could be experiencing “behavioral dysregulation: short fuse, irritability, [and] can’t suppress impulses the way you normally could.”

With these emotional problems, “they would be more prone to perhaps do something impulsive, like commit suicide,” Cantu, medical director of the Concussion Legacy Foundation, told CNN.

A second theory, Cantu noted, is that post-concussive symptoms prevent people from getting back into their sport and stop them “from being the person that they were before their injury.”

Neither theory is proven to the exclusion of the other, Cantu said, adding he thinks increased suicidality was “a combined factor involving both in many, if not most cases.”

There are also differences in the way brain injuries affect women.

A study of female soccer players across US high schools found they are nearly twice as likely to suffer concussion as their male counterparts, according to research that looked at over 80,000 adolescent athletes, published in the journal JAMA Network Open.

Women remain significantly underrepresented within sport and exercise science research: a 2021 study examining papers from some of the most influential sports medical journals found that only 6% of the studies were solely focused on women, compared with 31% of studies that included just men.

Other researchers have pointed to female sex hormones, with risk of concussion changing with hormone levels during a menstrual cycle.

McKee said all athletes can also experience “non-concussive” injuries: “hits to the head that can be of the same magnitude as concussion, but they don’t rise to the level of symptoms for whatever reason, so a player tends to play right through it.”

Cumulative exposure to repetitive head impacts – including concussion and non- concussive injuries – increases the risk for the neurodegenerative brain disease chronic traumatic encephalopathy, known as CTE, McKee said.

The disease, which can only be formally diagnosed with an autopsy, has mostly been seen in either veterans or people who played contact sports, particularly American football, say researchers. The disease occurs when the brain starts to degenerate likely due to repeated head traumas, according to the Mayo Clinic, which notes CTE is “associated with recurrent concussions.”

But scientists aren’t only concerned about concussions.

Previous studies have shown subconcussive head impacts – repetitive hits to the head and body that do not cause symptoms – can still result in long-term neurological disease.

According to The Concussion Legacy Foundation, “the best available evidence suggests that subconcussive impacts, not concussions, are the driving force behind CTE.”

There have been cases of CTE discovered in athletes who have never been diagnosed with a concussion, according to the Concussion Legacy Foundation.

And other changes in the brain after repetitive head impacts aside from CTE are likely “equally important,” McKee said.

“We also see damage to the white matter. And that appears to be mostly in the frontal lobe, but also in the temporal lobes,” she said.

“We’re trying to understand the relationship of those white matter changes to behavioral and mood symptoms, perhaps even suicidality,” she said.

McKee stressed that concussion management is important, but physicians and athletes should also be aware of other injuries.

“The problem is the subclinical hits – the non-concussive injuries that aren’t detected, you don’t pull the player off the field – and they can be in the hundreds or even the 1000s in a single season,” she explained.

Lack of research

Though a growing body of data suggests women in sport are more likely to sustain a concussion, have more severe symptoms, and to take longer to recover, most sports-related concussions protocols are based on data from men.

In a review in the British Journal of Sports Medicine, researchers looked at 171 concussion studies written since 1967 which are used to inform the most influential consensus and position statements in treating sports-related concussions.

Clinicians rely on these documents to guide their medical practice when treating athletes – but most of the studies are focused on men. Only 1% of them was looking exclusively at concussions in women and 40% of them didn’t have any women in a sample of participants at all.

There is another risk factor for women in sport when they sustain head injuries, Katherine Snedaker, founder and executive director of PINK Concussions, a non-profit dedicated to women’s health and brain injury, told CNN.

There is a gulf of millions of dollars separating women and men when it comes to average annual salaries in most professional sports.

Outside of elite sport, Snedaker says, female athletes often don’t have access to the same medical care as men, meaning head injuries aren’t spotted as routinely.

“They tend to push really hard through the injury,” she said.

And many women can’t afford to take time out to recover: even professional athletes will supplement their sports income with other jobs, she added, and many are caregivers.

“When they really crater, it’s a couple of days or weeks later.”

Snedaker said female athletes often weren’t aware they had suffered a head injury.

If they were, she said, there were no appropriate medical or sporting staff to inform.

Not enough support

The families of Catlin and Soutter feel the young women didn’t get enough support after their injuries.

After Catlin’s first suicide attempt, she was released from an involuntary admission to the psychiatric ward after threatening legal action, and a conference between psychiatrists, her coach and her parents.

She attended therapy sessions, which she agreed to attend during the conference, but found “they were geared toward suicidal freshman with a whole set of different issues than an elite Olympic athlete,” her father told CNN.

She got a referral to a sports psychologist that worked with the Stanford athletic department, but the department forbade the psychologist from seeing Catlin because she was not a varsity athlete, her father added.

She contacted the office of a sports psychologist with whom she had developed a rapport while in the hospital – but, his appointment secretary said he had no openings for six months, her father told CNN.

“Wherever she turned she could not find help,” he said, adding that his daughter tried a suicide hotline several times: she was once put on hold and once received no answer.

Catlin described his daughter as a “stoic, female warrior type person that isn’t going to admit that she’s struggling.”

“She needed a sports psychiatrist that really could understand what she was going through and understand the rigors of her life in terms of preparation for competitions and the athletic side of it and what it could potentially do to you.”

Her father said a major factor in his daughter’s death was “a lack of communication between the facilities that were involved in Kelly’s care. No one was in charge and they assumed the other institutions were following up when they weren’t,” he added.

In a statement sent to CNN, Luisa Rapport, director of emergency communications and media relations at Stanford University did not address any of the specific allegations made by Catlin’s family. She said while the university does not discuss in the media the details of individual students’ experiences, “supporting the mental and emotional health of students is a critical priority for Stanford.”

“Students in need of mental health crisis assistance – including students having suicidal thoughts – and those who are concerned about students in need of assistance, can contact the University’s Counseling and Psychological Services (CAPS) 24 hours-a-day, seven days-a-week,” she added.

Rapport said that in addition to this, “there are multiple places where psychological services may be provided for students depending on individualized need and treatment recommendations, including, for example, affiliated hospital services and clinics through Stanford’s Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, and mental health programs and clinicians in the community.”

In a statement sent to CNN, USA Cycling said it was “devastated” by Catlin’s death, adding: “She brought focus and determination to everything she did, and served as an inspiration to everyone who knew her.

“As the National Governing Body for the sport of cycling, USA Cycling prioritizes the holistic wellbeing of the riders on the U.S. National Team and has a longstanding commitment to providing both physical and mental health resources to members of the team,” a representative for USA Cycling added.

After his daughter Ellie’s death, Soutter was contacted by the UNITE Brain Bank, who wanted to study her brain as part of their research into CTE.

But even in that facility – the biggest of its kind in the world – of some 1,300 brains, only 3% belonged to women, Ann McKee, Director of the Boston University Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy (CTE) Center told CNN.

“When I actually started looking into CTE – all of the work that they’ve done with the footballers in America, she had every single symptom and more,” Soutter told CNN.

“It was quite obvious to me that there was a definite link in her starting to get into dark places and feeling bad and anxious and not sleeping properly. All of those symptoms … Every one that’s involved in CTE was part of Ellie’s life,” he added.

“I truly believe today that my daughter would be alive had I had any inkling, you know, even the smallest bit of information.”

Editor’s Note: If you are in the US and you or a loved one have contemplated suicide, call The National Suicide and Crisis Lifeline at 988 or 1-800-273-TALK (8255) to connect with a trained counselor.

For support outside of the US, a worldwide directory of resources and international hotlines is provided by the International Association for Suicide Prevention. You can also turn to Befrienders Worldwide.

Correction: A previous version of this story incorrectly stated the number of brains held at the Unite Brain Bank. It has now been updated.

CNN’s Krystina Shveda contributed reporting.