Editor’s Note: Hamid Dabashi is the author of “Iran Without Borders: Towards a Critique of the Postcolonial Nation,” and the Hagop Kevorkian Professor of Iranian Studies and Comparative Literature at Columbia University in New York. His most recent book is “The End of Two Illusions: Islam after the West” (University of California Press, 2022). The views expressed here are his own. Read more opinion on CNN.

The news that the Iranian Oscar-winning actor Taraneh Alidoosti was arrested at her home in Tehran on December 17 and taken to the infamous Evin prison rushed through the media like a brushfire.

Since the commencement of the massive social uprising in her homeland in mid-September, Alidoosti has been actively denouncing the ruling regime, supporting the “Woman, Life, Freedom” revolt and boldly criticizing the killing of protestors. Iranian women, many of them young women, and their supporters have been rising up against mandatory veiling, economic corruption and mismanagement, and 43 years of militant Islamist repression.

Alidoosti represents a vast and variegated spectrum of Iranian women filmmakers and actors who from the very beginning of cinema in their homeland have been actively putting the fate of their nation on the silver screen for the whole world to watch.

Within 48 hours after Alidoosti’s arrest, leading Iranian filmmakers gathered in front of Evin prison to express their support and solidarity with her, while the prominent filmmaker Asghar Farhadi, the Oscar-winning director of the films featuring her, publicly came to her defense. At the same time, world-renowned actors and directors from around the globe published an open letter denouncing her arrest. The signatories included Emma Thompson, Mark Rylance, Mark Ruffalo, Ken Loach, Mike Leigh, Steve McQueen, Ian McKellen, David Hare, Juliet Stevenson and the American-Iranian director Ramin Bahrani.

The ruling regime was put on global notice for its violent crackdown of mostly peaceful protests.

Role of women in Iranian cinema and society

Years ago, Jean-Michel Frodon, a prominent French film critic, said the late Abbas Kiarostami, the world-renowned Iranian filmmaker, was like a locomotive that carried the rest of Iranian cinema to the world’s limelight. The same is true today of Alidoosti, whose arrest and incarceration in the dungeon of a beleaguered and violent state have brought her people’s historic struggles for liberty to global focus.

From that iconic beginning, Iranian women have been at the forefront of their film industry in every capacity – from producers and directors to editors, sound engineers, set designers, directors of photography and actors. It is not accidental that today the word “Woman” stands at the forefront of the leading slogan of the first pronounced feminist uprising in the entire region with significant global consequences.

In the history of Iranian cinema, Roohangiz Saminejad is remembered as the first woman who dared social taboos and cultural mores and appeared in 1934 as the heroine Golnar in “Lor Girl,” the first Iranian talkie. Also known as “The Iran of Yesterday and the Iran of Today,” “Lor Girl” was the first sound film ever to be produced in the Persian language. When Shahla Riahi became the first Iranian woman filmmaker, she opened a door that would eventually lead to the rise of Forugh Farrokhzad, the first Iranian woman filmmaker to gain international attention with her 1963 classic “House is Black.”

The power of self-representation

By the time Marzieh Meshkini made her feature debut in 2000 with “The Day I Became a Woman,” a formidable constellation of Iranian woman filmmakers were behind and in front of the camera to tell their stories as they saw fit.

Today, a wide range of women filmmakers are active in Iran, embracing Alidoosti inside a powerful circle of self-representation the ruling Islamist regime can neither claim nor control. Such world-renowned filmmakers as Rakhshan Banietemad, Pouran Derakhshandeh, Tahmineh Milani, Marzieh Boroomand and countless others have emerged as potent critics of the masculine culture that remains institutionalized in the ruling government.

The confidence, the grace and the moral backbone with which Alidoosti has today stood up to a bullying and violent state that has completely lost any semblance of legitimacy did not fall from the sky. It is the result of generations of women’s rights activists and revolutionaries that go back to the middle of the 19th century when the Iranian counterparts of Abigail Adams, Mary Wollstonecraft, Susan B. Anthony, Sojourner Truth, bell hooks and Angela Davis were active in Iran, demanding and exacting their rights.

From before the Constitutional Revolution of 1906 to 1911, which turned an absolutist monarchy into a constitutional monarchy, to every major turn in modern Iranian history, conservative, liberal and radical women’s rights activists alike have left no stone unturned to assert their vision of a better future for themselves and their homeland.

Before the “Woman, Life, Freedom” uprising of 2022, women were active in other movements: the Green Movement of 2009; the reformist movement of the late 1990s; and International Women’s Day on March 8, 1979, when women staged the very first demonstration against mandatory veiling a month after Ayatollah Khomeini’s triumphant return to Iran.

The power of that historic demonstration was rooted in the active role of women in the Iranian revolution of 1977 to 1979 that brought the Pahlavi regime down and, before that, in the nationalization of Iranian oil industry that had resulted in the CIA and MI6-sponsored coup of 1953.

But all of that illustrious history does not do justice or fully account for the courage, conviction and principled uprising of a new generation of women and girls at the forefront of today’s massive social uprising that makes all its historic antecedent fade in comparison.

To be sure, men directors have not been entirely oblivious to the fate of women in their homeland, which has now flowered into this uprising. Throughout his cinematic career, Bahram Beyzaie has paid almost exclusive attention to recasting the social and cultural location of women in Iranian history. Another major filmmaker, Jafar Panahi, has devoted three of his masterpieces – “The Circle,” “Crimson Gold” and “Offside” – to the struggle of Iranian women for equality and justice.

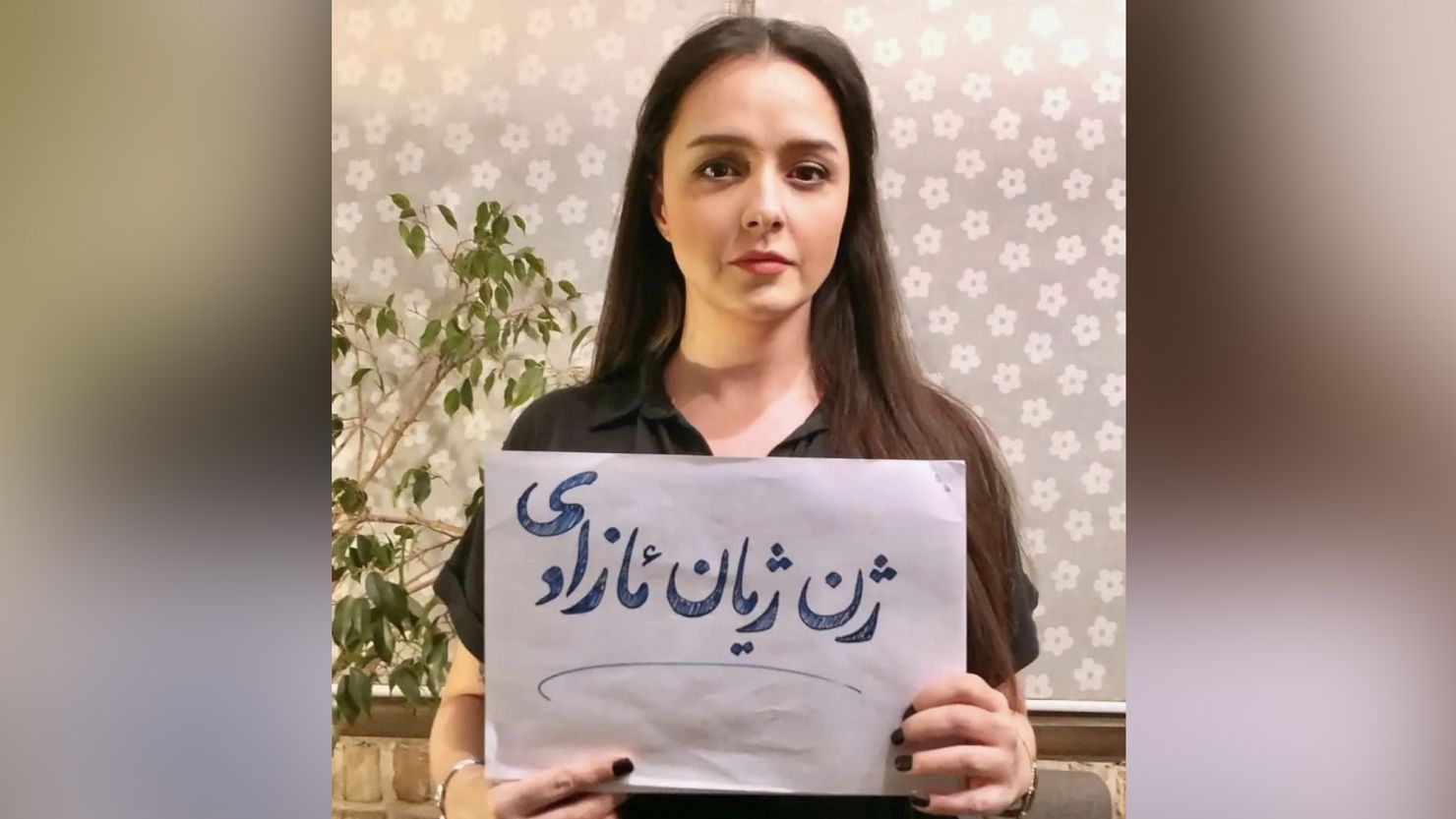

One of the principal charges against Alidoosti is that she posted on the internet a picture of herself, without any scarf, holding a sign that read, “Woman, Life, Freedom.” At the writing of this essay, there are countless renowned actors around the globe preparing a campaign taking their pictures with that sign in solidarity.

The message of this uprising that Alidoosti has championed extends far beyond her homeland. It has a global resonance that includes the United States where the 1973 landmark Roe v. Wade decision of the US Supreme Court was overturned in June, compromising the inalienable rights of women over their own bodies and putting the health and wellbeing of millions of poor Americans in jeopardy.

The cry of “Woman, Life, Freedom” that has landed Alidoosti in jail is a universal message that can be translated – and felt – in every language around the globe.