Editor’s Note: A version of this story appeared in CNN’s Meanwhile in China newsletter, a three-times-a-week update exploring what you need to know about the country’s rise and how it impacts the world. Sign up here.

It may be too early to call it a complete victory, but a collective uproar from people across China against stringent Covid controls has forced a remarkable partial climbdown from one of the world’s most authoritarian governments – and its leader, Xi Jinping.

Following protests nationwide, some local Chinese authorities have started to ease Covid restrictions – in what appears to be a shift toward gradual reopening as the country nears entering the fourth year of the pandemic.

Since last week, more than 20 cities, including the major metropolises of Beijing, Shanghai, Shenzhen, Wuhan and Chengdu, scrapped the requirements for negative Covid tests on public transport, if not other public venues.And some residential compounds now allow infected residents with special needs to quarantine at home, instead of being sent to centralized quarantine.

“I feel like everyone’s hard work is paying off,” said a protester who took part in a demonstration in Beijing.

China’s top health official signaled a change in strategy on Wednesday, by declaring the country’s pandemic controls had entered a “new stage and mission.” Xi later shared his thoughts on the issue with the visiting European Council President, according to an EU official who said the Chinese leader had acknowledged people were frustrated and suggested China was open to relaxing its Covid rules.

It was an extraordinary contrast to Xi’s ringing endorsement of the “tenacious pursuit” of zero-Covid at the Communist Party Congress in late October – back then, he made no mention of the public anger that had been simmering for months, or the soaring economic and social costs of the policy that he had personally backed.

Just six weeks ago, Xi’s authority seemed all but unassailable. He secured a groundbreaking third term in power, moved politically more moderate leaders into early retirement, and stacked the new leadership with staunch loyalists – including some of the most faithful enforcers of his zero-Covid strategy.

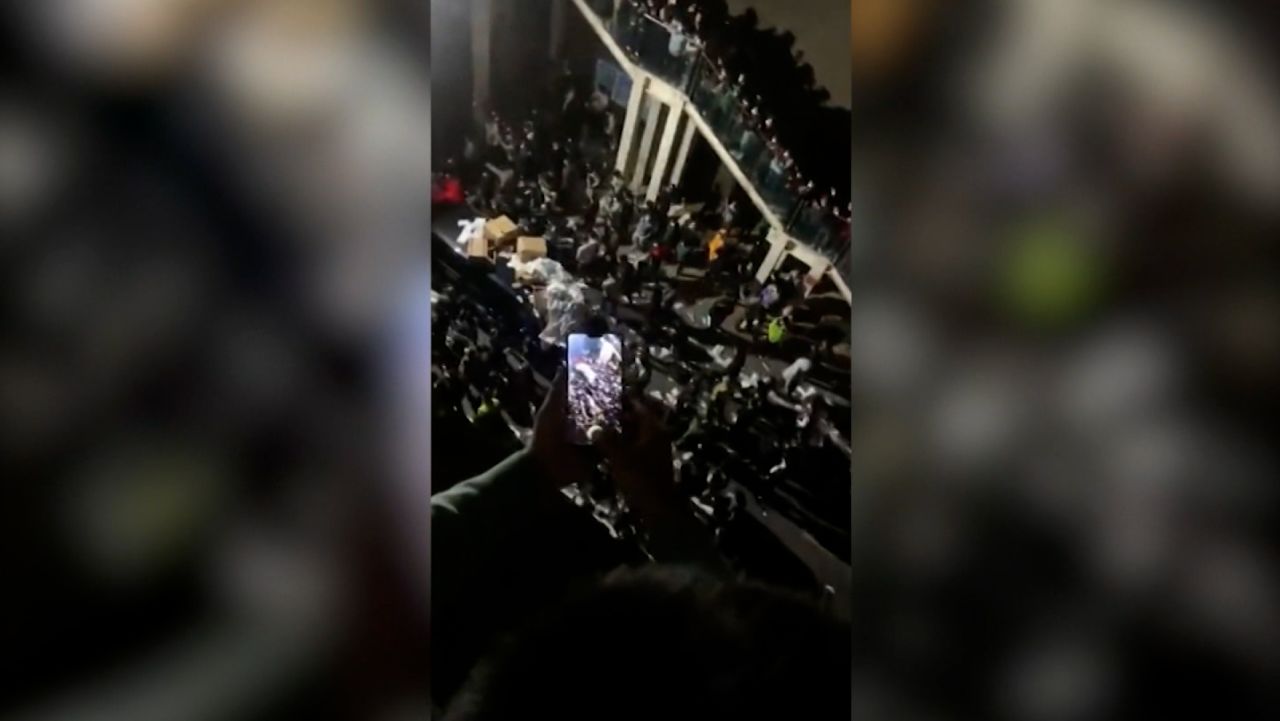

That image of unquestioned and absolute control was pierced late last month by an explosion of dissent from residents, migrant workers and university students who’d had enough.

In a worrying development for the party, in addition to Covid restrictions, many young protesters also directed their anger at Xi’s authoritarian policies, from ever-tightening censorship to all-encompassing ideological controls, which now dictate what they’re allowed to watch, read, listen to and buy in their private lives to an extent unseen in decades.

Some demanded greater political freedoms, others decried dictatorship and life-long rule, but the boldest political defiance came from Shanghai, China’s largest city and financial hub, where crowds openly called for Xi to “step down” for two consecutive nights.

While China’s security forces moved swiftly to snuff out the demonstrations, the growing calls for political change – unheard of on such a scale since the 1989 Tiananmen Square protests – have likely pushed authorities to speed up the easing of restrictions.

State media has carefully avoided all mention of the protests, instead framing the policy adjustment as following the science,a development noted by one Beijing resident in a widely circulated – and later censored – Weibo post: “When you talk to him about democracy, he finally talks to you about science.”

Having stoked pervasive public fear of catching and dying of Covid, Chinese state media is now citing months-old research on the comparative “decreased pathogenicity” of the Omicron variant. Some state media outlets also shared an interview with a medical expert who raised doubts about long Covid – a sharp contrast to previous coverage playing up the long-term risks of contracting the virus.

The about-face in public messaging is not lost on many Chinese people critical of zero-Covid. Some shared juxtaposed screenshots of two reports from the state-run People’s Daily published five months apart – one highlighting the severityoflong Covid, and one with the headline: “At present, there is no evidence showing long Covid exists.”

Despite the partial relaxation, many restrictions remain in place – and in some parts of the country, new lockdowns and travel restrictions are still being imposed.

“It appears that moving away from zero-Covid is pretty much a decentralized process in China: while some localities are easing restrictions, some allegedly still cling to zero-Covid, and still others are waiting and watching,” wrote Yanzhong Huang, a senior fellow for global health at the Council on Foreign Relations in New York. “Policy flip-flop is common.”

In some cities, the partial relaxation has caused confusion and chaos on the ground. In Beijing, public venues such as shopping malls and office buildings still require a 48-hour negative Covid test for entry. The abrupt removal of testing kiosks in the capital has also caused long lines at the remaining testing locations.

Still, residents across major Chinese cities shared photos of testing booths being removed from the streets, celebrating what some saw as the “beginning of the end” to zero-Covid.

Others are in no mood for celebration, citing the livelihood ruined and lives lost due to the draconian lockdowns.

“There will be no compensations, no apologies, no discovery of the truth, just moving on. What can lock us down can also easily unlock us. How terrifying is this capricious power, and when will it overturn your life again? I don’t celebrate, I just remember those brave friends with gratitude,” a Beijing resident posted on Weibo, in a reference to the protesters.

“Freedom does not fall from the sky.”