Editor’s Note: Sign up for CNN’s Fitness, But Better newsletter series. Our seven-part guide will help you ease into a healthy routine, backed by experts.

Despite volunteering and working out at the gym several days each week, socializing frequently with friends and family, reading all manner of books and doing daily crossword puzzles, 85-year-old Carol Siegler is restless.

“I’m bored. I feel like a Corvette being used as a grocery cart,” said Siegler, who lives in the Chicago suburb of Palatine.

Siegler is a cognitive “SuperAger,” possessing a brain as sharp as people 20 to 30 years younger. She is part of an elite group enrolled in the Northwestern SuperAging Research Program, which has been studying the elderly with superior memories for 14 years. The program is part of the Mesulam Center for Cognitive Neurology and Alzheimer’s Disease at Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine in Chicago.

“I’ve auditioned twice for ‘Jeopardy!’ and did well enough on it to be invited to the live auditions. Then Covid hit,” said Siegler.

“Who knows how well I would have done,” she added with a chuckle.“What I have told my children and anybody else who asked me: ‘I may know an awful lot about Beethoven and Liszt, but I know very little about Beyoncé and Lizzo.’”

What is a SuperAger?

To be a SuperAger, a term coined by the Northwestern researchers, a person must be over 80 and undergo extensive cognitive testing. Acceptance in the study only occurs if the person’s memory is as good or better than cognitively normal people in their 50s and 60s.

“SuperAgers are required to have outstanding episodic memory — the ability to recall everyday events and past personal experiences — but then SuperAgers just need to have at least average performance on the other cognitive tests,” said cognitive neuroscientist Emily Rogalski, a professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at Feinberg School of Medicine.

Only about 10% of people who apply to the program meet those criteria, said Rogalski, who developed the SuperAger project.

“It’s important to point out when we compare the SuperAgers to the average agers, they have similar levels of IQ, so the differences we’re seeing are not just due to intelligence,” she said.

Once accepted, colorful 3D scans are taken of the brain and cognitive testing and brain scans are repeated every year or so. Analysis of the data over the years have yielded fascinating results.

Bigger, tau-free neurons

Most people’s brains shrink as they grow older. In SuperAgers, however, studies have shown the cortex, responsible for thinking, decision-making and memory, remains much thicker and shrinks more slowly than those of people in their 50s and 60s.

A SuperAger’s brain, usually donated to the research program by participants after death, also has bigger, healthier cells in the entorhinal cortex. It’s “one of the first areas of the brain to get ‘hit’ by Alzheimer’s disease,” said Tamar Gefen, an assistant professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at Northwestern, in an email.

The entorhinal cortex has direct connections to another key memory center, the hippocampus, and “is essential for memory and learning,” said Gefen, the lead author of a November study comparing the brains of deceased SuperAgers with those of older and younger cognitively normal people and people diagnosed with early Alzheimer’s.

SuperAger brains had three times fewer tau tangles, or abnormal formations of protein within nerve cells, than the brains of cognitively healthy controls, the study also found. Tau tangles are a hallmark sign of Alzheimer’s and other dementias.

“We believe that larger neurons in the entorhinal cortex suggest that they are more ‘structurally sound’ and can perhaps withstand neurofibrillary tau tangle formation,” Gefen said.

Gefen also found the brains of SuperAgers had many more von economo neurons, a rare type of brain cell, which so far has been found in humans, great apes, elephants, whales, dolphins and songbirds. The corkscrew-like von economo neurons are thought to allow rapid communication across the brain. Another theory is that the neurons give humans and great apes an intuitive advantage in social situations.

The von economo neurons were found in the anterior cingulate cortex, which forms a collar in the front of the brain linking the cognitive, reasoning side with the emotional, feeling side. The anterior cingulate is thought to be important for regulating emotions and paying attention — another key to good memory.

Taken together, these discoveries appear to point to a genetic link to becoming a SuperAger, Gefen said. However, she added: “The only way to confirm whether SuperAgers are born with larger entorhinal neurons would be to measure these neurons from birth until death. That obviously isn’t possible.”

Can environment play a role?

SuperAgers share similar traits, said Rogalski, who is also the associate director of the Mesulam Center for Cognitive Neurology and Alzheimer Disease at Feinberg. These folks stay active physically. They tend to be positive. They challenge their brain every day, reading or learning something new — many continue to work into their 80s. SuperAgers are also social butterflies, surrounded by family and friends, and can often be found volunteering in the community.

“When we compare SuperAgers to normal agers we see that they tend to endorse more positive relations with others,” Rogalski said.

“This social connectedness may be a feature of SuperAgers that distinguishes them from those who are still doing well but who are what we would call an average or normal ager,” she said.

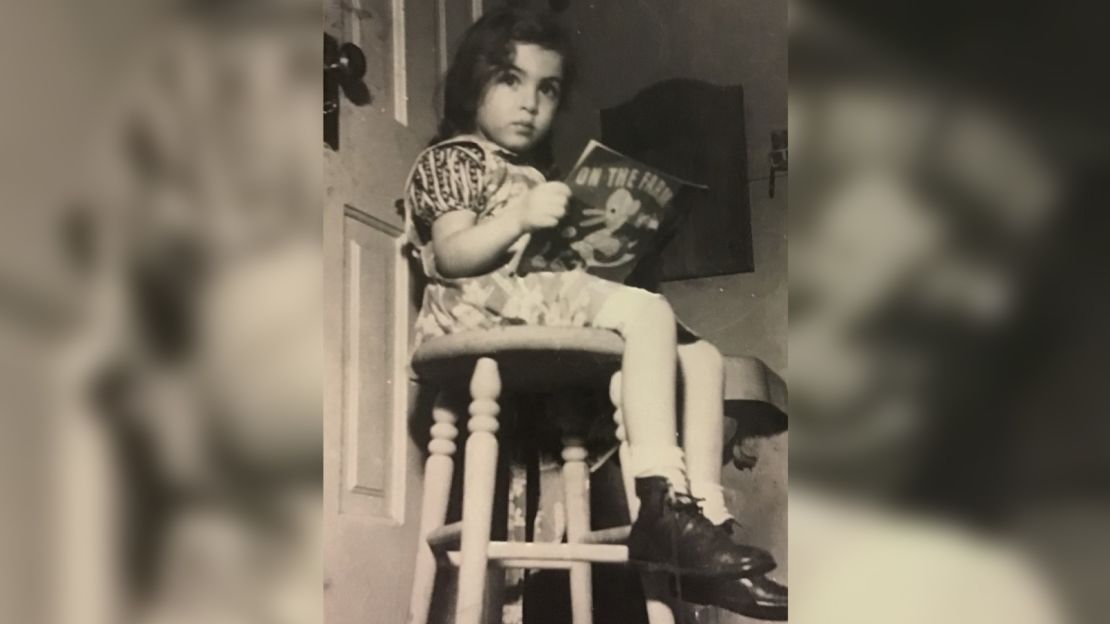

Looking back at her life, Carol Siegler recognizes many SuperAger traits. As a young child during the Great Depression, she taught herself to spell and play piano. She learned to read Hebrew at her grandfather’s knee, poring over his weekly Yiddish newspaper.

“I have a great memory. I’ve always had it,” Siegler said. “I was always the kid that you could say, ‘Hey, what’s Sofia’s phone number?’ and I would just know it off the top of my head.”

She graduated from high school at 16 and immediately went to college. Siegler got her pilot’s license at age 23 and later started a family business in her basement that grew to have 100 employees. At 82, she won the American Crossword Puzzle Tournament for her age group, which she said she entered “as a gag.”

After seeing an advertisement for the SuperAger program on television, Siegler thought it too sounded like fun. Being chosen as a SuperAger was a thrill, Siegler said, but she is aware she was born lucky.

“Somebody with the same abilities or talents as a SuperAger who lived in a place where there was very little way to express them, might never know that he or she had them,” she said. “And that is a true shame.”