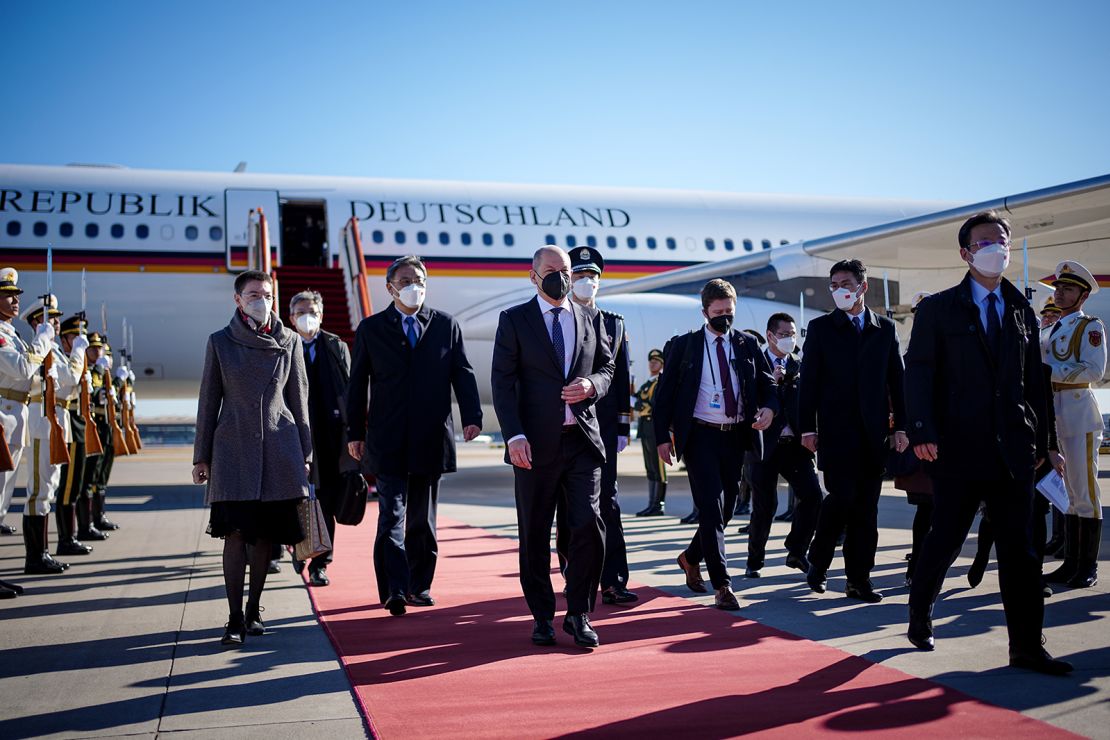

German Chancellor Olaf Scholz arrivedin China on Friday with a team oftop executives, sending a clear message: business with the world’s second-largesteconomy must continue.

Scholz met with Chinese leader Xi Jinping at Beijing’s Great Hall of the People after landing in the capital Friday morning and was received by Premier Li Keqiang in the afternoon.

Joining Scholz for the whirlwind one-day visit is a delegation of 12 German industry titans, including the CEOs of Volkswagen (VLKAF), Deutsche Bank (DB), Siemens (SIEGY) and chemicals giant BASF (BASFY), according to a person familiar with the matter.They were expected to meet with Chinese companies behind closed doors.

The group entered China without undergoing a mandatory seven-day hotel quarantine standard for most arrivals. Images showed hazmat-clad medical workers greeting Scholz’s jet at Beijing’s Capital International Airport to test the official delegation for Covid-19 upon their arrival.

During the Friday morning meeting between the two leaders, Xi called for Germany and China to work together amid a “complex and volatile” international situation, and said the visit would “enhance mutual understanding and trust, deepen pragmatic cooperation in various fields and plan for the next phase of Sino-German relations,” according to a readout from state broadcaster CCTV.

Speaking at a press conference with Premier Li, Scholz said that Germany’s economic relationship with China had recently become “more difficult” because Beijing was making access to some of its markets more difficult.

“We are seeing discussions in China tending more towards autonomy and less economic ties. And these views are ones that need discussing,” Scholz said.

Scholz’s visit — the first by a G7 leader to China in roughly three years — comes as Germany slides towards recession. But it has fired up concerns that the interests of Europe’s biggest economy are still too closely tied to those of Beijing.

Since Moscow’s invasion of Ukraine this year, Germany has been forced to ditch its long dependence on Russian energy. Beijing has declared its friendship with Moscow has “no limits,” whileChina’s relations with the United States are deteriorating.

Now, some in Scholz’s coalition government are growing nervous about Germany’s ties with China.

The tension was highlighted recently by a fierce debate over a bid by Chinese state shipping giant Cosco to buy a 35% stake in the operator of one of the four terminals at the port of Hamburg. Under pressure from some members of the government, the size of the investment was limited to 24.9%.

The potential deal has raised concerns in Germanythat closer ties with China will leave critical infrastructure exposed to political pressure from Beijing, and disproportionately benefit Chinese companies.

But Germany is hardly in a position to rock the boat with Beijingas it grapples with the challenge of reviving its struggling economy. Its consumers and companies have borne the brunt of Europe’s energy crisis, and a deep recession is looming.

If the European Union and Germany were to decouple from China, it would lead to “large GDP losses” for the German economy,Lisandra Flach, director of the ifo Center for International Economics, told CNN Business.

The Kiel Institute for the World Economy estimatesthat a major reduction in trade between the European Union and China would shave 1% off of Germany’s GDP.

Germany needs to shore up its export markets as ties with Russia, once its main supplier of natural gas, continue to unravel.

When it comes to China, Germany won’t want to “lose also this market, this economic partner,” said Rafal Ulatowski, an assistant professor of political science and international studies at the University of Warsaw.

“They [will] try to keep these relations as long as it’s possible.”

Pressure on Berlin

As Western countries have imposed swingeing economic sanctions on Russia, China has publicly maintained its “neutrality” in the war while ramping up its trade with Moscow.

That has triggeredabacklash in Europe, where some companies are already becoming wary of doing business in China because of its stringent “zero Covid” restrictions.

Pressure on Berlin is also mounting over China’s human rights record. In an open letter Wednesday, a coalition of 70 civil rights groups urged Scholz to “rethink” his trip to Beijing.

“The invitation of a German trade delegation to join your visit will be viewed as an indication that Germany is ready to deepen trade and economic links, at the cost of human rights and international law,” they wrote in the memo, published by the World Uyghur Congress. Based in Germany, the organization is run by Uyghurs raising awareness of allegations of genocide in China’s Xinjiang region.

It suggested Berlin was “loosening economic dependence on one authoritarian power, only to deepen economic dependence on another.”

In an op-ed published in a German newspaper on Wednesday, Scholz said he would use his visit to “address difficult issues,” including “respect for civil and political liberties and the rights of ethnic minorities in Xinjiang province.”

A spokesperson for the German government addressed wider criticism last week, saying at a press conference that it had no intention of “decoupling” from its most important trading partner.

“[The chancellor] has basically said again and again that he is not a friend of decoupling, or turning away, from China. But he also says: diversify and minimize risk,” the spokesperson said.

Last year, China was Germany’s biggest trading partner for the sixth year in a row, with the value of trade up over 15% from 2020, according to official statistics Chinese trade with Germany was worth a combined €245 billion ($242 billion) in 2021.

A new flashpoint

Still, the furor surrounding the Hamburg port deal is a reminder of the tradeoffs Germany has to confront if it wants to maintain close ties with such a vital export market and supplier.

A spokesperson for Hamburger Hafen und Logistik (HHLA), the company operating the port terminal, told CNN Business on Thursday that it was still negotiating the deal with Cosco.

Flach, of the ifo Center for International Economics, said the deal warranted scrutiny because “there is no reciprocity: Germany cannot invest in Chinese ports, for instance.”

However, it is easy to overstate the impact of the potential agreement, said Alexander-Nikolai Sandkamp, assistant professor of economics at the Kiel Institute for the World Economy.

“We’re not talking about a 25% stake in the Hamburg harbor, or even the operator of the harbor, but a 25% stake in the operator of a terminal,” he told CNN Business.

Jürgen Matthes, head of global and regional markets at the German Economic Institute, told CNN Business that critics were no longer simply weighing the business benefits of Chinese investment in the country.

“Politics and economics have to be looked at together and cannot be taken separately any longer,” he said. “When geopolitics comes into play, the view of China has very much declined and become much more negative.”

China’s recent treatment of Lithuania has also deepenedconcerns that Beijing “does not hesitate to simply break trade rules,” Matthes added. The small, Eastern European nation claimed last yearthat Beijing had erected trade barriers in retaliation for its support for Taiwan.

China has defended its downgrading of relations with Lithuania, saying it is acting in response to the European nation undermining its “sovereignty and territorial integrity.” This year, after a Lithuanian official visited Taiwan, Beijing also announced sanctions against her and vowed to “suspend all forms of exchange” with her ministry.

What’s on the table

As the German delegation touched down on Friday, they were facedwith another issue, which has become the single biggest headache for companies across China.

“The biggest challenge for German businesses remains China’s zero-Covid policy,” said Maximilian Butek of the German Chamber of Commerce in China.

“The restrictions are suffocating economic growth and heavily impact China’s attractiveness as a destination for foreign direct investment,” he told CNN Business.

He said the broader restrictions were so stifling that some companies had moved their regional headquarters to other locations, such as Singapore. “Managing the whole region without being able to travel freely is almost impossible,” he added.

In a brief statement, Volkswagen told CNN Business that its CEO was attending the trip since “there have been no direct meetings for almost three years” due to the coronavirus pandemic.

“In view of the completely changed geopolitical and global economic situation, the trip to Beijing offers the opportunity for a personal exchange of views,” the automaker said.

End of a golden era?

Despite Beijing’s Covid curbs and geopolitical tensions, Germany has every economic incentive to stay close to China.

Its dependency on China can be seen across industries. While about 12% of total imports came from China last year, the country was responsible for 80% of imported laptops and 70% of mobile phones, Sandkamp said.

The automobile, chemical and electrical industries are also reliant on Chinese trade.

“If we were to stop trading with China, we would run into trouble,” Sandkamp added.

China made up 40% of Volkswagen’s worldwide deliveries in the first three quarters of this year, and it’s also the top market for other automakers such as Mercedes.

Wariness among some German officials over the country’s closeness with China could filter into a more restrictive trade policy, though economic cooperation is still in both parties’ interests.

In September, Germany’s economy minister Robert Habeck told Reuters that the government was working on a new trade policy with China to reduce dependence on Chinese raw materials, batteries and semiconductors.

Unidentified sources also told the news agency that the ministry was weighing new rules that would make business with China less attractive. The ministry did not respond to a request for comment from CNN Business.

But “despite all odds and challenges, China remains unrivaled in terms of market size and market growth opportunities for many German companies,” said Butek, of the German Chamber.

He predicted that “the large majority will stay committed to the Chinese market and is expecting to expand their business.”

Companies appear to be toeing that line. Last week, BASF CEO Martin Brudermüller was quoted in Chinese state media as saying that Germans should “step away from China-bashing and look at ourselves a bit self-critically.”

“We benefit from China’s policies of widening market access,” he said at a company event, according to state-run news agency Xinhua, pointing to the construction of a BASF chemical engineering site in southern China.

— CNN’s Simone McCarthy, Chris Stern, Lauren Kent, Nadine Schmidt, Claudia Otto and Arnaud Siad contributed to this report.