Editor’s Note: This personal essay is part of the CNN Opinion series “America’s Future Starts Now,” in which people share how they have been affected by the biggest issues facing the nation and experts offer their proposed solutions. Chimére L. Smith is a former middle school teacher in Baltimore who has suffered from long Covid since March 2020. She is now an advocate for Black families on long Covid. The views expressed in this commentary are her own. Read more opinion on CNN.

In June 2020, I lay on my bed, willing myself not to cry again.

It was a Friday morning, and I had been fighting off tears since I arrived home after spending the night in the hospital, waiting to be seen. While I waited, I could hear doctors and nurses breezing by my door, but it took hours for them to come in. I thought I knew why; I had been there before – at least half a dozen times.

Each time I wanted the same thing: relief from my lingering symptoms of Covid-19. This time was no different.

Nurses greeted me kindly, but stared at me in disbelief as I stated, yet again, that I felt like my brain was on fire. Later, the doctors would enter in succession.

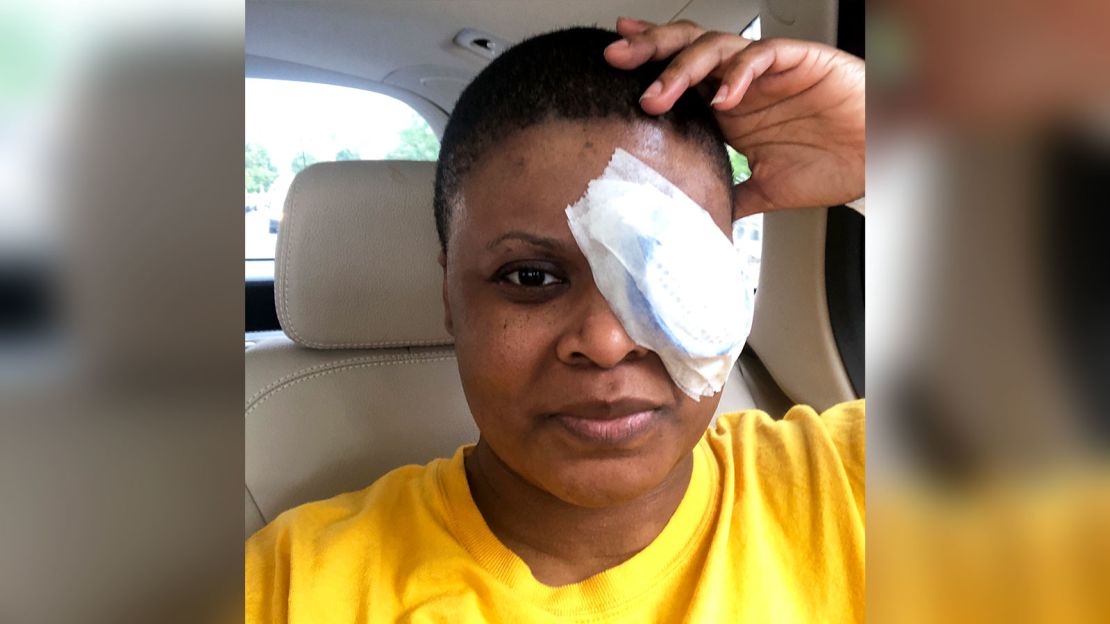

First, a doctor to check my eyes, since I had inexplicably lost vision in my left eye months before. Then, the neurologist with yet another cognitive function test that she claimed I passed with flying colors. She asked me to wiggle my toes and fingers, yet she didn’t probe for information about the fire that threatened to melt my brain, nor did she ask why I couldn’t remember my name on some days.

Finally, the emergency department doctor stopped by. He was the one I dreaded most, as he was usually the one who would tell me, “We checked all your blood work. We found nothing. We’re going to send you home.”

I was used to this treatment; most doctors I spoke to since I had become ill – many of whom were White males – didn’t believe I had Covid-19, preferring instead to assume I had a psychological issue. Some suspected drug use or insisted I was being abused at home. And others seemed to roll their eyes because of the number of Covid-19 tests – both antigen and antibody – I had taken, all of which were negative.

The pandemic was a new beast for the public and health care professionals alike; experts even admitted that they were learning about the disease in real time. The fact that my symptoms were accompanied by a negative test should not have been cause to write off the possibility that I had contracted Covid-19.

So, on that Friday morning, thoroughly overwhelmed by pain and desperation, I couldn’t hold back my tears any longer.

A few months prior, just as communities began to shutter for the pandemic, I was pretty sure I had caught Covid-19. My symptoms started with a sore throat and diarrhea, but soon snowballed into a living hell: constipation, burning lungs, dehydration, stomach aches, delirium, memory loss, joint and muscle pain, sleeplessness, weight loss and loss of vision in my left eye. And they wouldn’t stop.

Months of excruciating pain, fear and hospital visits later, I was at my wit’s end. I was an English teacher, but I wondered if I’d ever teach again (to this day, I’m still not able to). My best friend had a copy of my will and knew how to manage my final wishes. I had nearly lost my will to live.

Somehow, I found the strength to not only push through my physical pain, but also to push back on a system that wasn’t taking my pain seriously. I had had enough of being tossed aside. I got angry.

Fueled by desperation, my burning brain started drumming up ideas. I had to save my own life. I crafted a detailed email to the patient relations coordinators of the hospital I’d been treated at. I shared my growing number of debilitating symptoms and my experience of not being taken seriously. I admitted that although I had never tested positive for Covid-19, I knew I had it. And I accused them of allowing doctors to dismiss me.

America's Future Starts Now

In that email, I became who I never wanted to be: a confrontational, complaining Black woman.

I didn’t care.

Once I started writing, I couldn’t stop. I wrote to my local city council and state delegate leaders. I wrote to journalists, informing them of “long Covid” – the new term coined by a growing number of people on Twitter, who described the lingering, frightening symptoms many of us faced after the initial viral infection. I reached out to prestigious neurologists, pleading for help. I even wrote Google reviews for doctors who refused to acknowledge that I had a suspected case of long Covid.

Days later, email responses started to pour in. I cried as I read a note from a city council member who offered sympathy and agreed to advocate for me. And a state delegate wrote to a top hospital official about my situation.

With the help of those politicians, I received notices from one of the hospital’s patient relations offices, agreeing to investigate my case. We scheduled meetings to discuss appointments with specialists who would oversee my care. Finally, I was being taken seriously – and I was about to get answers.

Challenging conversations with a new primary care physician finally led to my diagnosis of “post- acute Covid syndrome.” Covid-19 infections, it turns out, can cause inflammatory responses in various parts of the body, which had led to many of my symptoms. With a diagnosis, I was able to get proper treatment, including cataract surgery to repair my vision loss, and qualify for leave from work and disability benefits.

Now, nearly three years after my Covid-19 infection, I am doing a bit better. I can cook, drive to appointments, read and have hour-long phone conversations with family and friends. My will to live has been restored.

But my new life, which includes days of pain, brain fog, exhaustion and persistent eye issues, has left me unable to teach the students I cherished. I laugh at the money playing peekaboo in my bank account after exhausting all my leave benefits. And, some days, crying is all I can do.

Being an advocate for long Covid sufferers, especially those of color, has now become a part of my life’s mission. I have been able to use my experience to advocate for the long Covid community and others who aren’t being heard in our health care system. But I miss the woman I was and the life I led.

In December 2020, when I was invited to speak as a guest panelist for the National Institute of Health’s workshop on the effects of long Covid, I immediately said yes. It was my golden opportunity to warn the world’s top doctors and researchers about what would happen if the medical community missed the mark again by forgetting Black and Latino people in communities with little money, access to information or treatment options. Following this global discussion, Congress provided $1.15 billion over four years to the NIH’s research of long Covid.

But there’s still so much work to be done to make health care – and long Covid care – more equitable. Though this virus affected Black and brown people at a higher rate, I rarely saw Black long Covid patient stories at the forefront of conversations about this disease. I only had to look back on my own experience to understand why: To be heard I had to get mad enough to challenge medical authority, ask questions, complain and agitate. I had to disrupt a system designed to exclude me and people who look like me.

So, I’ll keep speaking up, and encourage other Black men and women to speak up with me.

I know, firsthand, how effective it can be.