Near a dry, red rock peninsula on Australia’s far western coast, a dusty highway separates two communities with contrasting fortunes tied to an ancient land.

One is home to the small but booming city of Karratha, a regional hub scattered with four-wheel drives that was purpose-built in the 1960s to accommodate a growing army of miners looking to extract the land’s vast stores of iron ore, oil and gas.

The other is Roebourne, a former gold rush town 30 minutes up the highway, where the peninsula’s Indigenous population settled after being driven from their lands by colonialists in the mid-1800s.

For years, news reports painted Roebourne as a “misfit town where everyone drinks, smokes and can’t take care of their kids,” says Josie Alec, a proud descendent of the Kuruma-Marthudunera people, who raised her four kids there.

In reality, she says it’s a deeply resilient community made up of families like her own, whose ancestors have watched over “Murujuga” – the peninsula’s Aboriginal name – for generations,while keeping its vibrant cultural traditions alive.

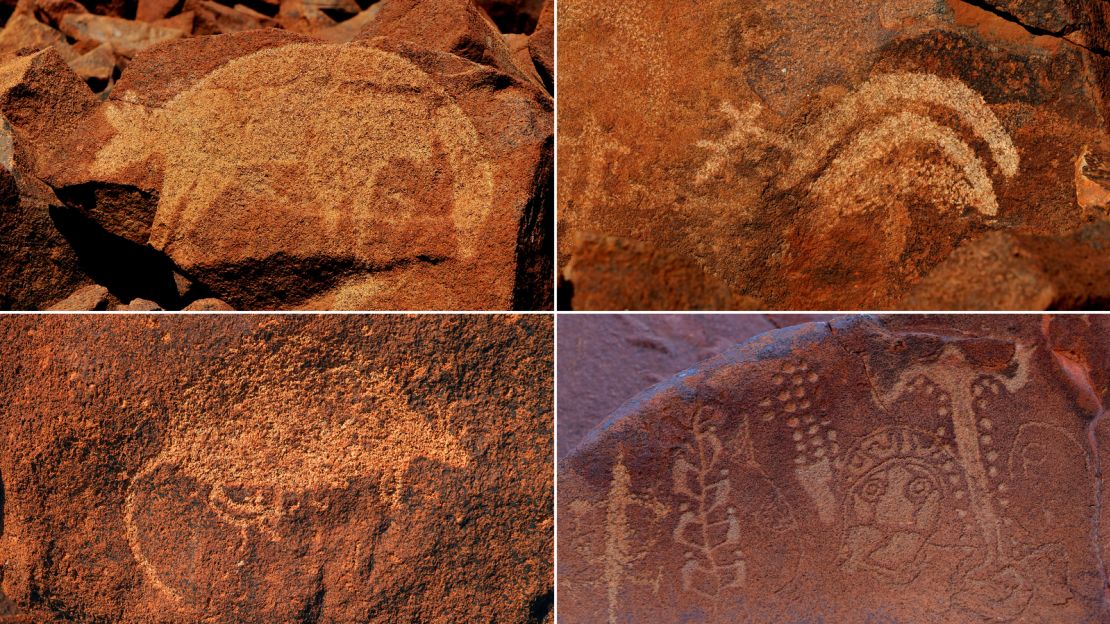

For Australia’s First Nations people, Murujuga is the birthplace of songs and creation stories explaining the laws of nature, told through more than a million rock carvings scattered across its deserts and nearby islands.

These irreplaceable petroglyphs are 10 times older than the pyramids of Egypt and depict early human civilization, but some of their ancestral guardians fear they could be destroyed by pollution from one of Australia’s largest new fossil fuel developments.

The company behind the project, Woodside Energy, plans to extract millions of tons of gas from the Scarborough field in the Indian Ocean mostly for export to north Asia.

Not only is there widespread concern about the sky high greenhouse gas emissions the project is expected to generate over its lifetime, but there are also fears that industrial pollution from its processing plants could erode Murujuga’s petroglyphs, which show now-extinct animals and plant species, as well as some of the earliest known depictionsof the human face.

Woodside argues the impacts of its expansion have been “thoroughly assessed” by environmental regulators and says it supports a program by the Murujuga Aboriginal Corporation (MAC) and the state government to assess risks to the rock art, which is due to file its first report next year.

MAC is the legally appointed Aboriginal body tasked with advising government and companies on the cultural implications of development on the peninsula.

While MAC doesn’t receive mining royalties, critics argue its ability to object to Woodside’s plans is limited by longstanding agreements, and its reliance on industry for funding has created frustration and resentment among other members of the community who say it’s not doing enough to protect ancestral treasures.

Mining country

Murujuga is part of Australia’s Pilbara region, a thinly populated area twice the size of the United Kingdom known for its ancient landscapes, dry red deserts, and vast mineral resources.

To White settlers it’s always been mining country.

The promise of gold and pearl brought colonists to the Pilbara in the 1880s, but today companies are more interested in its stores of iron ore, oil and gas.

Resources extracted from the region have powered Australia’s economy and helped create some of the world’s largest mining and energy multinationals.But a comparatively small slice of the overall proceedshas filtered back to First Nations people, many of whom say their land has been exploited and sacred sites destroyed.

And it keeps happening.

Last month federal environment minister Tanya Plibersek said she wouldn’t intervene to stop plans by Perth-based multinational group Perdaman to build a new fertilizer plant on the peninsula – a development requiring some sacred rocks to be relocated.

“This idea that Perdaman is going to suddenly be built on that landscape is just unbelievable, absolutely unbelievable,” said Benjamin Smith, a professor of World Rock Art at the University of Western Australia, who has spent years studying Murujuga’s petroglyphs.

In a June paper, co-authored with other eminent rock experts, Smith found that industrial pollutants from other development on the peninsula – namely nitrogen oxides – are already eroding the outer layer of Murujuga’s petroglyphs, causing the carvings to slowly disappear.

The paper draws on other published studies that “agree that the rich red-brown patina of Murujuga’s rocks, as with other forms of rock varnish, is dissolved with increasing acidity.” Smith says acid levels increase when sulphur and nitrogen oxides emitted from the industrial plants on Murujuga mix with moisture.

Smith’s findings contradict previous research – partly funded by industry – that claimed there was “no adverse impact to the rock engravings from industrial pollution,” which Woodside uses to back its claim that its gas plant activities aren’t harming the petroglyphs.

In a statement to CNN, Woodside said: “Peer-reviewed research has not demonstrated any impacts on Burrup (Murujuga)rock art from emissions associated with Woodside’s operations.”

Smith and other experts have long argued that the raw data used to support those findings is flawed.

In June, the Western Australian Environment Protection Agency (EPA) pointed to a lack of consensus on the issue and said it “considers that there may be a threat of serious or irreversible damage to rock art from industrial air emissions,” of which “the most significant sources” are Woodside’s existing gas plants.

Last week, the federal government responded to requests to assign an independent consultant to carry out a full cultural heritage assessment of all industry on Murujuga, with their findings to be reported to the environment minister – who will then decide if the site is worthy of an official order to protect it.

‘My family story lies in those rocks’

The independent review was the result of intense lobbying by Alec and Marthudunera woman Raelene Cooper, two traditional custodians, who traveled to Genevain July to tell the United Nations that the potential destruction of Murujuga’s rocks would amount to “cultural genocide.”

The two women started visiting the countryside around Murujuga as children in the 1970s and 80s – around the same time Woodside arrived on the peninsula to begin construction on its sprawling Karratha gas complex.

For Cooper, that meant floating down the Fortescue River on hot days, while watching the local mothers wash their clothes and prepare food.

“I’d swim in the river, have a feed out bush (eat outdoors). We knew industry was there, but we didn’t see it … back then even the iron ore mines were out of sight,” she said.

Like a lot of young First Nations people living across the Pilbara, Cooper eventually found herself working in the mines. For three years, she operated heavy machinery for Rio Tinto, but quit after questioning the damage it was doing to country.

“I realized my job was to protect Murujuga, not dig it up. The economy here shouldn’t just be about breaking up the earth and sucking everything out of it.”

In 2016, Cooper was elected as one of MAC’s board members, a role she proudly occupied for more than five years until February, when she resigned over the corporation’s support of Woodside’s Scarborough development.

“I felt the elders were being manipulated and had no understanding of the risks the project posed. It broke my heart to leave, but I couldn’t support MAC approving the removal of our history,” she told CNN.

For Alec, protecting Murujuga is part of a journey to heal the bonds severed with her ancestors when she was forcibly removed from her mother as a baby and placed in foster care under a government policy from 1910 to the 1970s to “assimilate” First Nations children. The policy created what’s known as the Stolen Generation, who carry the trauma of separation from their people. At the time, the government claimed it was for their own good.

“Growing up as an Aboriginal girl in a White world was tough, but I had a really good foster mom and dad and a strong family,” Alec told CNN.

Alec’s adoptive parents eventually brought her back to Murujuga to meet her birth mother and learn about her ancestors.

By the time she was a teenager, she was making regular trips to Roebourne and its surrounding countryside, and it was there she began discovering the traditional healing techniques her family was known for – by learning to read Murujuga’s rocks.

“My mom was the shaman of the tribe, everyone came to her for healing, and eventually she passed that down to me.”

“My family story lies in those rocks … They take me home, so that’s why I fight so hard for them,” she told CNN.

A tale of contrasting fortunes

The contrast between extreme wealth and poverty that’s come to define the Pilbara is clear in the recent histories of Roebourne and Karratha.

While Karratha transformed from a small resource town to a regional city, Roebourne battled poverty, alcoholism and racial violence. In the 1980s, the town was thrust into the national spotlight after a First Nations teenager died in a police cell, provoking fury and an inquiry into Aboriginal deaths in custody.

Today, the fight for Murujuga’s rock art reflects long-standing and unresolved issues of race and power.

The United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples states that consent from First Nations people for projects on their land should be provided freely, without coercion or manipulation, and that the self-determination and sustainability of their communities should be at the core of all negotiations.

But in Australia, that’s rarely been the case.

Until the early 1990s, experts say little thought was given to Indigenous land rights due to the concept of “terra nullius,” which held that the continent belonged to no one before White settlement.

In 1992, Native Title law was written to recognize Indigenous land rights, but it was only designed to secure First Nations people a share of the profits from exploration or mining activities on their lands, not to stop developments altogether.

In order to avoid lengthy legal battles, Native Title lawyers say governments and big industry have historically sought out potential claimants ahead of proposed developments – using negotiated agreements to acquire their land in exchange for financial benefits.

Indigenous activists and Native Title lawyers describe this alleged practice as a “divide and conquer” technique which can cause bad blood between families because it pits traditional custodians against one another.

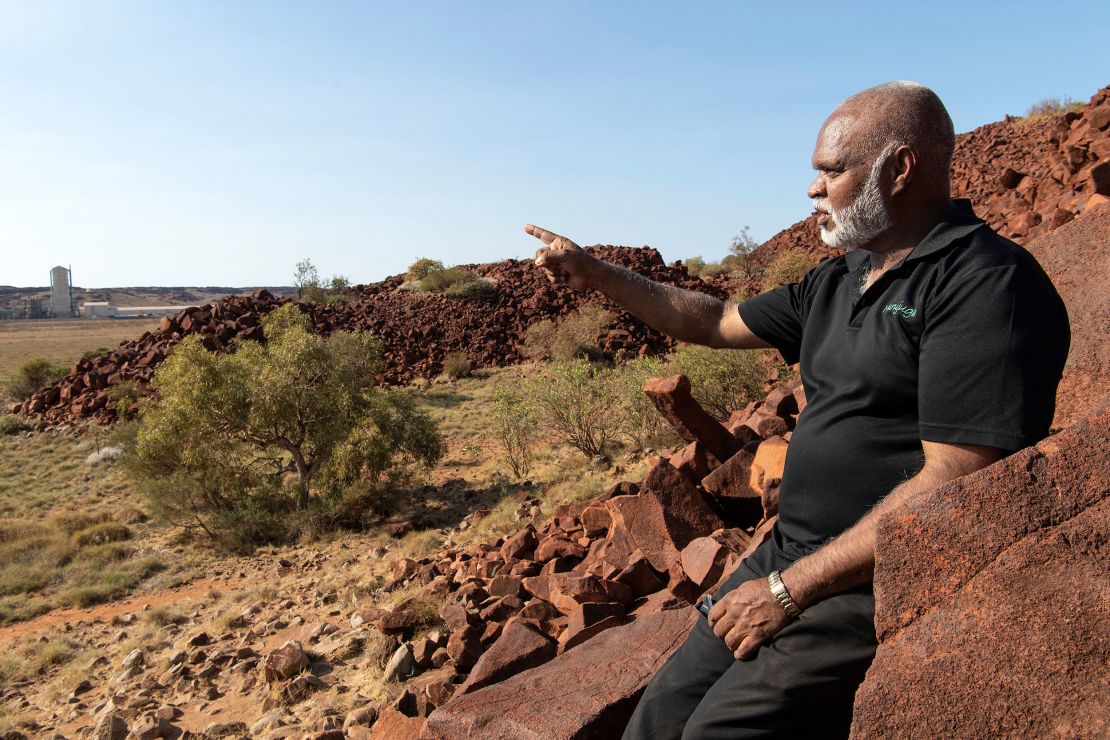

“Government and industry have this unique ability to foster division in vulnerable Aboriginal communities,” said Kado Muir, a Ngalia Traditional Owner and Chairman of The National Native Title Council.

“They create a faction who endorses and signs off on the agenda a developer brings. Then eventually, the community is torn apart, and the cycle of poverty and dispossession continues.”

‘A volatile place to speak your truth’

In 2003, the Western Australian government compulsorily acquired Native Title on Murujuga through the Burrup and Maitland Industrial Estates Agreement (BMIEA) – a contract signed by the region’s Ngarluma-Yindjibarndi, Wong-Goo-Tt-Oo, and Yaburara Mardudhunera peoples.

In exchange for surrendering their land rights to the state government for the purpose of industrial development, the Aboriginal groups party to the BMIEA received financial benefits along with the freehold title of the Murujuga National Park.

The agreement also led to the establishment of MAC as the approved corporate body, which shares management of the park with the state government and whose rock monitoring program receives funding from businesses that operate on the peninsula – Woodside, Rio Tinto and fertilizer company Yara Pilbara.

MAC’s reputation among locals is polarizing, with activists like Alec and Cooper openly questioning its independence due to the funding it receives from industry.

Members of the group have spoken publicly about the power imbalance that stems from those financial ties, including its CEO Peter Jeffries.

In a June letter to the Department of Agriculture concerning the Perdaman fertilizer development, seen by CNN, Jeffries, a senior Ngarluma man, said the Circle of Elders that advise MAC repeatedly stated their preference that the rocks at the site weren’t moved, before agreeing to the company’s proposals to shift a small number.

More broadly, he wrote, “There are serious issues that need to be addressed regarding the quality of negotiation between Aboriginal Corporations and proponents … where proponents only consider a negotiation to be complete upon receiving the answer they want.”

Jeffries was less candid when he spoke with CNN about Woodside’s project, in an interview arranged by the managing director of a public relations firm, who asked to sit in on the call.

The firm – which also provides services for Woodside’s joint-venture partner BHP and the state government’s development agency – told CNN that MAC was the only “approved cultural authority” to speak about developments on Murujuga, and that it was crucial “the right information” was being shared about the views of traditional custodians in relation to the Scarborough expansion.

In the interview, Jeffries was guarded when asked about MAC’s relationship with Woodside and its reliance on big industry for funding.

“In partnerships, you’ve got to take the good with the bad … we have to work with industry, they’ve been here for 30-40 years and they’ll continue to be here, so it’s about how we co-exist,” he said.

Local leaders are uneasy about the influence they say Woodside has over MAC, and in March, 27 elders from Murujuga wrote an open letter to the Western Australian government, calling for “independent” financing for the organization, so it could “manage the cultural heritage of Murujuga without being compromised by relying on Woodside.”

In a statement to CNN, Woodside said it had “engaged and consulted extensively with Traditional Owners about the Scarborough Project since 2019” and it was “pleased” with the support it had from Murujuga’s custodians.

MAC is under intense pressure from all sides – but First Nations activists CNN spoke with say that blaming Aboriginal corporations detracts from the real problem.

“It’s easy to look in from the outside and say that Traditional Owners on the Pilbara are ‘pro-mining,’ but it’s a volatile place to speak your truth about what’s taking place on country,” said Larissa Baldwin, a Widjabul First Nations Justice Campaign Director at GetUp, a not-for-profit that advocates for progressive policy change in Australia.

“People are afraid of having their livelihoods threatened in a place where there is no other economy,” said Baldwin. “It’s the kind of power imbalance that puts Indigenous communities in a place of duress.”

Powering Asia

Woodside hopes the first gas piped from the offshore Scarborough field will be processed and sent to Asian markets in 2026.

The company’s awaiting final sign-off from Australia’s offshore regulator but otherwise it has the go-ahead from state and federal legislators.

The new Labor government led by Prime Minister Anthony Albanese has promised higher cuts to emissions than its predecessor but maintains gas is a “transition energy” as the world moves to renewables.

That stands at odds with the International Energy Agency’s assessment that the world won’t reach its target of net zero emissions by 2050 if governments approve new oil and gas developments.

Gas, in general, is less carbon-intensive than coal, but it’s still a planet-warming fossil fuel, and there is a growing understanding that its infrastructure leaks huge amounts of methane – a more potent greenhouse gas than carbon dioxide in the shorter term – undermining the bridge fuel argument.

Woodside estimates the project will pump out 967 million tons of carbon emissions over its lifetime. But researchers at Climate Analytics say that figure will be closer to 1.5 billion tons from 2021 until the project winds down in 2055 – about the same amount of emissions Australia produces every three years.

Woodside has told CNN it is committed to using technology to reduce nitrogen oxide emissions across its operations while it awaits the results of the rock art monitoring program, but it also confirmed that no new investment had been made into pollution control measures for its infrastructure since 2008.

Smith says the existing body of science shows Murujuga’s rocks won’t survive the coming decades if the Scarborough project goes ahead – due to the sheer scale of its projected emissions.

“It’s an obvious no-brainer … there should be no new developments on Murujuga,” Smith said. “The world is turning against people like Woodside that make vast profits at the expense of the planet and the expense of our heritage.”

Smith also expressed concern about the transparency of the rock art monitoring program due to the absence of independent oversight and a lack of access to its raw data.

“At the moment, we don’t have access to any of the data that has been produced. It has ‘confidentiality’ written all over it. It shouldn’t,” he said.

“I cannot see any reason for secrecy of any form of something that is of such public interest.”

A spokesperson for the state Department of Water and Environmental Regulation (DWER) said the raw data will be peer-reviewed by a panel of scientists selected by the government in mid-2023 after the first full year of monitoring. The raw data will not be published, the spokesperson confirmed.

In a country that’s built its fortunes on mining and stands to make billions of dollars in gas exports in coming decades, few political avenues exist to stop Woodside’s expansion.

There’s no statutory timeframe for the independent assessor’s report into development on Murujuga, and in the meantime Perdaman and Woodside are pushing ahead with their projects.

Alec and Cooper have welcomed the extra scrutiny, but they say the government’s refusal to grant an earlier request to halt the Perdaman plant “reveals the hypocrisy at the heart of all consultation between traditional custodians and industry.”

Perdaman declined CNN’s requests for comment.

Alec and Cooper say they won’t back down until they’re convinced Murujuga will be protected.

“The rocks are ancient beings,” Alec said. “My job as a custodian is to share our stories and spread awareness in a way that makes people feel and understand the power of this place.”

“It’s a very personal fight,” Cooper added. “But it’s a fight for all of our people and for Australia.”