Editor’s Note: A version of this story appeared in CNN’s Meanwhile in China newsletter, a three-times-a-week update exploring what you need to know about the country’s rise and how it impacts the world. Sign up here.

The future looked promising for Cherry in May last year, when she secured a prestigious internship at a major software firm, while still studying at a university in Wuhan. The company told her that she could start working for them full time, once she graduates.

But her situation changed dramatically this summer. Just as Cherry was about to graduate from university this year and start her job, she was told by the company that her offer has been rescinded as it had to “adjust” its business and cut staff.

Her peers received similar calls.

“I think it’s because of the pandemic,” the 22-year-old said. “Most companies have been affected by Covid lockdowns this year.”

She asked to only be referred to as Cherry, for fear of reprisals from future employers.

A sweeping crackdown by Beijing on the country’s private sector, that began in late 2020, and its unwavering commitment to a zero-Covid policy, have hit the economy and job market hard.

“Us fresh graduates are definitely the first batch of people to be laid off, because we just joined the company and haven’t made much contribution,” Cherry said.

A record 10.76 million college graduates entered the job market this year, at a time when China’s economy is losing the ability to absorb them.

The youth unemployment rate has repeatedly hit new highs this year, rising from 15.3% in March to a record 18.2% in April. It continued to climb for the next few months, reaching 19.9% in July.

The rate fell slightly to 18.7% in August, but still remains among the highest ever, data from the National Bureau of Statistics showed on Friday.

That means there are currently about 20 million people aged 16 to 24 out of work in cities and towns, according to CNN calculations based on official statistics that put the urban youth population at 107 million. Rural unemployment isn’t included in official data.

“This is certainly China’s worst job crisis for young people” in over four decades, said Willy Lam, a senior fellow of the Jamestown Foundation in Washington D.C.

“Mass unemployment is a big challenge for the Communist Party,” he said, adding that providing economic growth and job stability is key to the Party’s legitimacy.

And, perhaps nowhere is the crisis more visible than in the tech sector, which has been suffering from the regulatory crackdown by the government and far-reaching US sanctions against China.

The once-freewheeling industry was long the main source of high-paid jobs for young, educated workers in China, but major companies are now downsizing at a scale not seen before.

Alibaba (BABA), the e-commerce and cloud titan, recently posted flat revenue growth for the first time since becoming a public company eight years ago. It reduced its workforce by more than 13,000 in the first six months of this year.

This is the biggest reduction in its staffing since Alibaba was listed in New York in 2014, according to CNN calculations based on its financial documents.

Tencent (TCEHY), the social media and gaming giant, let go nearly 5,500 employees in the three months to June. This was the biggest contraction in its workforce in more than a decade, according to its financial records.

“The significance of these latest tech industry cuts cannot be understated,” said Craig Singleton, senior China fellow at the DC-based Foundation for Defense of Democracies.

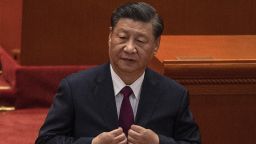

The job crisis in the tech sector, the industry Chinese leader Xi Jinping once proclaimed would drive the next phase of China’s development, could undermine his ambitions of turning the country into an innovation leader and a global tech superpower in the next two to three decades.

“These latest cuts represent a dual threat for Beijing going forward — not only do thousands of people unexpectedly find themselves out of work, but now these Chinese tech giants will have fewer qualified employees to help them innovate and scale-up to take on their Western competitors,” Singleton said.

“There is a saying in business circles that ‘if you are not growing, you are dying,’ and that simple truth threatens to undermine China’s broader technological ambitions,” he added.

Social instability

Tech isn’t the only sector suffering. In the past few months, mass layoffs have engulfed once booming Chinese industries ranging from private tutoring to real estate.

This could be a major problem for Xi and his government, which has characterized employment as a top policy priority.

“There are growing indications that the tenuous trust that exists between the Chinese people and the Chinese Communist Party is starting to fray, which could lead to a breakdown in social cohesion,” Singleton said.

This year, China has already witnessed some unprecedented protests among its middle class. A growing number of desperate home buyers across the country have stopped repaying mortgages, as the real estate crisis escalates and developers are unable to finish homes in time.

Protests also erupted in central China earlier this year, as thousands of depositors couldn’t access their savings at several rural banks in the region.

The unemployment issue has come at a sensitive time for the Chinese leader, experts said. Xi is seeking a historic third term when the Communist Party hold its congress next month.

“The party congress is so close now that I don’t see any significant risk that lay offs will interrupt the preparations for Xi to be nominated, and accept, a ground breaking third term of office,” said George Magnus, an associate at the China Centre at Oxford University.

But youth unemployment will constitute a “major threat” to China’s economic and political stability in the long run, he added.

It is not as if the government isn’t aware of the problem, but so far it has not been able to come up with any concrete solutions.

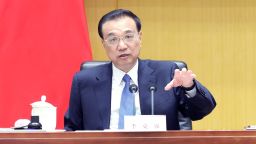

Chinese Premier Li Keqiang — the No. 2 in the hierarchy of the Communist Party — has been vocal this year about China’s sputtering economy, and has repeatedly stressed the need to stabilize the “complex and grave” job situation.

Authorities have encouraged young people to pursue tech entrepreneurship or seek jobs in the countryside to ease the pressure.

In June, the ministries of education, finance, civil affairs, and human resources and social security jointly issued a statement, ordering local governments to offer tax incentives and loans and attract college graduates to work as village officials or to start businesses there.

But the government seems unwilling to tackle the main reason behind China’s economic slowdown this year — the zero Covid policy. Even as the rest of the world learns to live with Covid, China continues to shut major cities where only a small number of cases erupt. A least 74 cities were under full or partial lockdowns earlier this month, affecting more than 313 million people, according to CNN calculations.

These restrictions are hurting the world’s second biggest economy badly — analysts are forecasting growth of just 3% or under for this year. Excluding 2020 — when the pandemic started in China — it would mark the country’s lowest annual growth since 1976.

But the Covid policy is likely to stay in place for several months, as Xi will not want to see any uncontrollable rise in Covid cases until his political future is secured, experts said.

According to Magnus, “the likelihood is that China will try and muddle through the next several years, with a high risk of economic instability.”

For graduates like Cherry — who is still unemployed — this means giving up her dreams of joining the tech industry and turning to lower-paid government jobs for stability.

“I wanted to work for internet companies straight after graduation, because I’m so young,” she said.

“But because of this incident, my thinking has changed. I think it’s good to have stability now.

CNN’s Mengchen Zhang in Beijing contributed to this report.