Editor’s Note: Peniel E. Joseph is Barbara Jordan chair in ethics and political values and founding director of the Center for the Study of Race and Democracy at the LBJ School of Public Affairs at the University of Texas at Austin, where he is a professor of history. He is the author of “The Third Reconstruction: America’s Struggle for Racial Justice in the Twenty-First Century.” The views expressed here are his own. View more opinion on CNN.

Growing up in Brooklyn and Queens in the 1980s, I was saved by the study of Black history. It helped me to make sense of the police shootings of Black people, the segregated schools I attended and the all-Black neighborhoods that I lived in. Beginning in childhood, my mother became my history teacher and intellectual raconteur.

The lessons that I learned growing up about the power of storytelling to change politics, legislation and the ways entire communities related to each other, reverberate now more than ever.

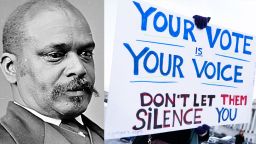

I cling to those memories now, amid our current moment of partisan division, rancorous debates over the teaching of American history, controversies over voting rights and confrontations over the meaning of the events of January 6, 2021. I know that the stories we tell each other about the nation we live in have taken on a new sense of urgency.

Personally, I have been invigorated by efforts – as a scholar, an active citizen and a husband and father – to tell a more complicated, uncomfortable, but ultimately more satisfying narrative about America’s past, present and future, and my (and our) place in it.

These two sides have been battling for America’s soul since 1865

America’s present has the power to transform its history, and vice versa. “It’s been a long time coming, but tonight because of what we did on this day, in this election, at this defining moment change has come to America,” then-President-elect Barack Obama observed to the cheering throng in Grant Park in Chicago. Obama’s historic election night in November 2008, like the Thirteenth Amendment’s passage and ratification in 1865 and the Supreme Court’s Brown v. Board of Education decision ordering desegregation in 1954, opened up a new political world. All three moments introduced new possibilities for how Americans defined citizenship.

The image of Obama standing on stage as president-elect of the United States of America breathed new and animating life into the Thirteenth and Brown – transforming Americans’ understanding of their own history. For some, this was a revelation. For others, it constituted an existential threat.

To appreciate why, it’s important to discern that most Americans’ understanding of their history since the end of the Civil War has been split between a “reconstructionist” perspective – adopted by supporters of multiracial democracy – and a “redemptionist” point of view – offered initially by former Confederates and later by advocates of White supremacy.

The stakes of the battle between them have long been the nation’s very soul. Understanding the American story requires learning about the nation’s history through a set of new eyes that allows us the vision to see both the grandeur and travails of our ongoing democratic experiment. In so doing we get to witness the historical parallels and political juxtapositions that show us that history, while never exactly repeating itself, most definitely rhymes.

These contrasting approaches have shaped more than our history; they have also influenced (and still play a role) in how Americans have defined citizenship, national identity and democracy since 1865.

How the first and second Reconstructions changed our story, over and over again

Jim Crow America was largely ruled by a redemptionist hand. At the turn of the 20th century, for instance, redemptionist politics were mainstream enough for a resurgence of the Ku Klux Klan to take place (it was revived in 1915 in Stone Mountain, Georgia, where a monument to White supremacy remains today). “The Birth of a Nation,” D. W. Griffith’s silent film portraying Reconstruction as a horrible mistake, was released in February of that year and became a sensation (it was screened for an approving President Woodrow Wilson at the White House).

Mass violence was perpetrated in multiple American cities in the years following, including a massacre in Tulsa, Oklahoma, in 1921 in which White people murdered over 300 Black people and razed a prosperous, all-Black neighborhood (Greenwood) to the ground.

Struggles for Black dignity that reached a low point in Tulsa’s aftermath, took on new and vital dimensions after the Second World War. During the Second Reconstruction, which unfolded from the Supreme Court’s 1954 Brown decision until the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr. in 1968, reconstructionists won important legislative victories in bills declaring formal segregation unconstitutional. None were more significant than the 1964 Civil Rights Act and the 1965 Voting Rights Act.

America’s Second Reconstruction transformed the social compact for Black folk, and the legacies from this period still reverberate nationally. We are still engaged in debates over voting rights, citizenship and dignity that roiled the nation during the 1950s and 1960s. The Second Reconstruction institutionalized support and unprecedented consensus around the value of Black equality to the strength of democracy, as a political and moral good.

Though Brown, in 1954, marks the beginning of the Second Reconstruction, the origin date for the emergence of a national consensus on racial justice could be traced to June 11, 1963, when President Kennedy delivered a televised address on the issue. That evening Kennedy spoke more candidly about racial inequality than ever before, noting that Blacks were “not yet freed from social and economic injustice” and that this fact negatively impacted the entire country. America, Kennedy observed, “for all its hopes and all its boasts, will not be fully free until all its citizens are free.”

Although there were setbacks, false starts, outright lies and performative gestures in the years that followed, and the achievements fell far short of the ambitious goals of reconstructionists, rhetorical support for racial justice proved much better for the nation’s democratic health than its opposite.

What a Third Reconstruction means

In retrospect, America enjoyed a 50-year period of affirmation of racial justice between JFK’s finest moment as president and the June 25, 2013, “Shelby v. Holder” Supreme Court decision, which gutted the Voting Rights Act. What the broader consensus had helped to mask was the continuing division over the federal government’s role in guaranteeing Black citizenship and dignity.

Reconstructionist thought situates America as a multiracial democracy, one free, in word and deed, of the ancient bonds of discrimination and racial injustice.

In the wake of the Second Reconstruction, redemptionists pledged support for racial justice, too, but not for federal intervention, which they interpreted as a violation of constitutional principles and the sanctity of states’ rights and individual preference. From the Shelby decision in 2013 to current midterm debates over how to address race and gender in the classroom, the nation is missing the racial justice consensus that fostered the rough compromises that allowed for racial progress to move at such a pace to lead to the election of a Black president.

Many politicians who adhered to redemptionist thinking apparently failed over more recent decades to spot the paradox between claiming proof that America was no longer a racist nation and supporting policies, from the blocking of anti-discrimination measures to the passage of laws that stymied voting rights and fueled mass incarceration, that resulted in the amplification of Black misery, suffering and premature death even if these outcomes were not always the intent. Among the effects were ongoing residential and public-school segregation, high rates of unemployment, imprisonment and housing discrimination, which largely shut Black families out of the wealth created through home ownership.

As the nation moved into the Third Reconstruction that started with Obama’s election and continued through the January 6 insurrection at the US Capitol building in 2021 and the investigative hearings that dominated the news this year, the racial cold war produced striking juxtapositions between racial progress and setbacks.

Black history saved me. It can save America, too

For as long as I can remember, I have been a student of American history. Its grace and its horrors helped me make sense of my own familial history, as the proud son of Haitian immigrants who moved to New York City in the mid-1960s. “Eyes on the Prize,” the monumental documentary series first broadcast on television in 1987, during my freshman year in high school, brought the history of the civil rights movement to life in my household over six glorious hours. The series treated Black people with deep empathy; suggesting their stories were worthy of respect.

And then in the summer before turning 17, I saw Spike Lee’s “Do the Right Thing,” which premiered on July 21, 1989. The film, set in the Bedford Stuyvesant neighborhood of Brooklyn, documented the anatomy of a race riot triggered by police violence.

The film’s portrayal of the afterlife of the civil rights movement – a city still scarred by segregation, poverty and racial discrimination – mirrored my own experiences. The police killing of a young Black man named Radio Raheem, who spends most of the film blaring Public Enemy’s “Fight the Power!” from a boom box, made the film a touchstone for me and an entire generation of young African Americans.

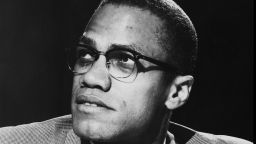

The movie’s coda, which drew quotes about Black dignity from Malcolm X and Black citizenship from Martin Luther King Jr., stayed with me and inspired me to turn my love of history into a lifelong vocation.

I discovered new worlds in history books, echoes of earlier freedom struggles – some victorious and others short-lived – that nonetheless served as inspiration for me to find out where I fit into a narrative that seemed larger than the one offered during the course of my secondary education.

In college I majored in history and Black Studies and stumbled into an interest in Reconstruction that only grew after I went to graduate school. But even completing a doctorate in American history on the civil rights era, a time period I came to later view as America’s Second Reconstruction, left me unsatisfied with the stories we tell about the nation’s past.

Dissatisfaction grew into determination, and I found myself using the study of history as both an intellectual shield and political sword capable of explaining the links between contemporary instances of structural racism and backlash and long forgotten episodes of inequality that served as the origin story for our latest political woes.

But it was not until 2020’s political and racial reckoning, when I watched millions of people around the world look to history to heal a troubled global soul, that I realized that there were so many people in search of a story that could help them make sense of things. The more I tried myself to make sense of the murder of George Floyd, the rise of then-President Donald Trump and his MAGA supporters and the grace and dignity of the Black women who led the Black Lives Matter movement, the more I turned to history.

I believe that the more we learn about these three periods of Reconstruction the better off we will all be. Understanding the origins of our current discontents allows us the collective power to choose a different path. This requires that we confront the dark parts of American history while holding on to the freedom dreams of Black, White, Latinx, Asian American and Pacific Islander, Indigenous, queer, disabled, working class and immigrant communities that have transformed this nation for the better.

Our first two reconstruction periods ended prematurely, wrecked by political violence, partisan divisions and a failure to craft a new narrative of American history courageously inclusive enough to deal with the bitter and beautiful parts of our history. This latest reconstruction period offers the profound opportunity to begin to shape a new more compassionate, ethical and morally redemptive story of America. That new story, beyond the history books, national commemorations and evolving political culture, starts with each of us. All we have to do is choose.